- SPEECH

Cash still king in times of COVID-19

Keynote speech by Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Deutsche Bundesbank’s 5th International Cash Conference – “Cash in times of turmoil”

Frankfurt am Main, 15 June 2021

Thank you for inviting me to speak today about “cash in times of turmoil”.

Even before the pandemic, the future of cash was being discussed as the use of digital payments accelerated. But the pandemic has raised the volume of that debate significantly. It has sped up the digitalisation of our economy – by seven years, according to recent estimates[1] – and led to new consumer behaviours. This in turn has led to renewed questions about whether cash has a future in the digital economy.

In my remarks today, I would like to explain why faster digitalisation does not spell the end for cash any time soon. Cash continues to play a crucial role in the euro area, and there is still demand for it. Though its use as a means of payment has declined during the pandemic, demand for cash has risen.

For this reason, the Eurosystem is committed to safeguarding cash. We are taking concrete steps to guarantee that cash continues to be available and accepted as a means of payment well into the future – including if we launch a digital euro.

Cash demand in times of COVID-19

The pandemic has triggered diverging developments in the use of cash.

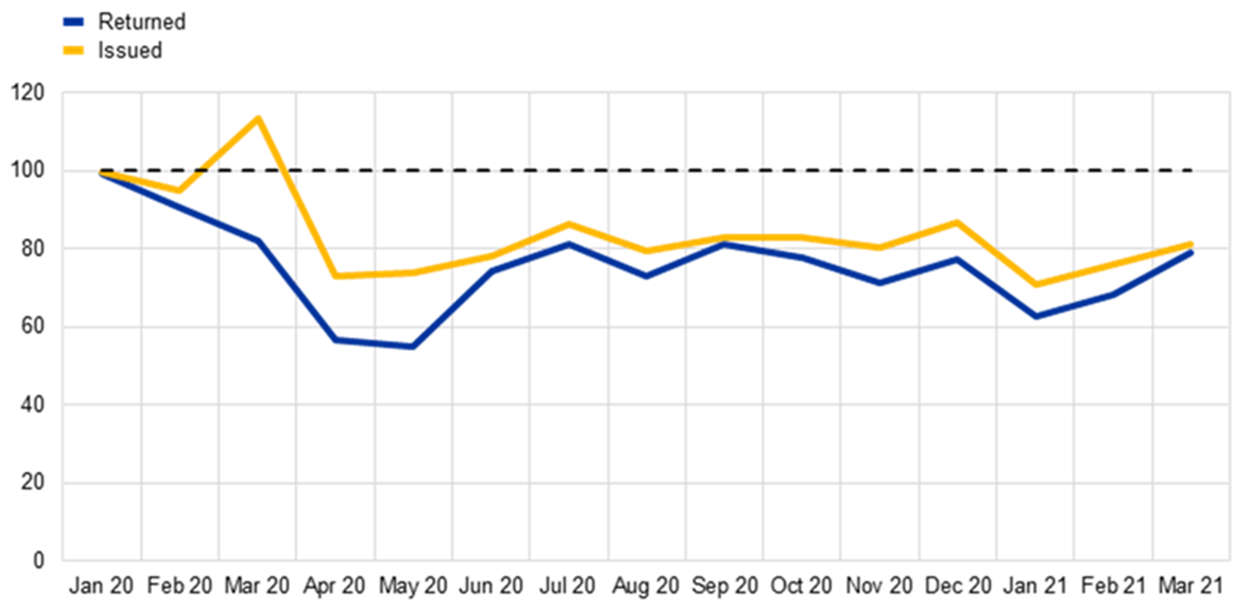

First, it has markedly decreased the use of cash in day-to-day payments. Since early last year, the volume of cash being lodged at central banks and commercial banks has fallen by around 20-25% in the euro area (Chart 1). A survey commissioned by the Eurosystem in mid-2020 showed that around 40% of the respondents were using cash less frequently than before[2].

Chart 1

Share of the value of banknote flows in 2020 as a percentage of flows of the five previous years (2015-19)

(percentage)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Banknote flows (issued and returned) are compared with the average flows of the previous five (normal) years. The latest observation is for March 2021.

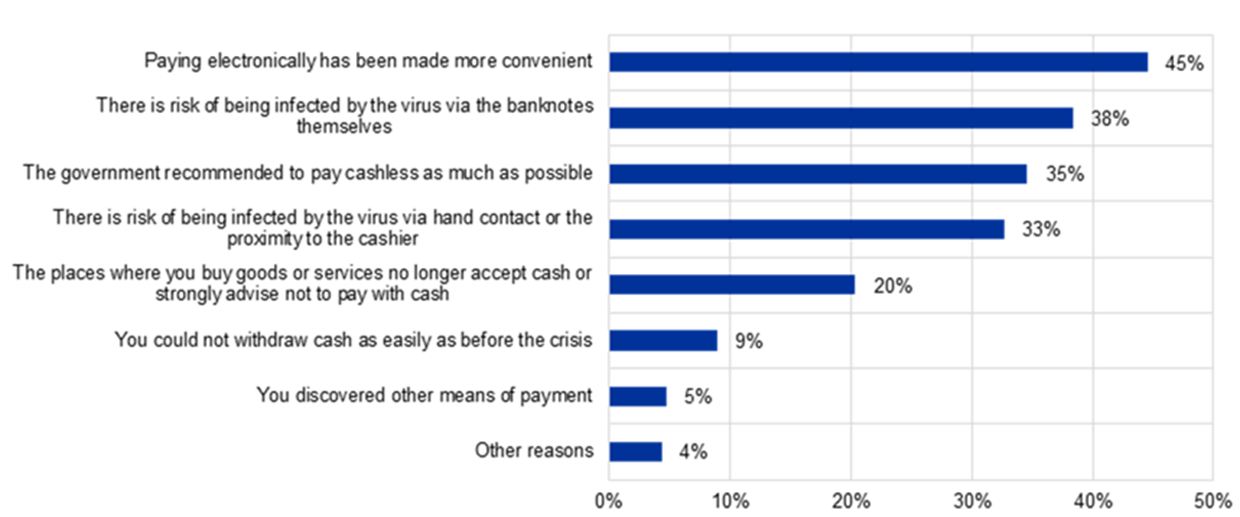

The reasons for the decline in cash payments are well-known. They range from the expansion of e-commerce to the restrictions introduced to fight the pandemic, which have had an impact on cash-intensive activities like travelling, leisure and cultural events. The same survey found that consumers have shifted away from cash as electronic payments have become more convenient or owing to concerns about the risk of infection, advice not to pay with cash or because cash was becoming less widely accepted (Chart 2).[3]

Chart 2

Main reasons for changing payment behaviour during the pandemic

Source: ECB.

It was obviously crucial for the Eurosystem to address people’s fears of becoming infected through the use of cash. We therefore commissioned analyses by top-tier laboratories as early as March 2020. The results confirmed that the risk of transmission via banknotes and coins is very low, and thus cash remains safe to use. Overall, the coronavirus mainly spreads via aerosols and airborne transmission, and surfaces in any case play only a very minor role.[4]

However, despite the significant drop in the use of cash for payments, we have seen a parallel, huge rise in the demand for euro banknotes over the past year: an increase of €190 billion – or €550 per capita – between March 2020 and May 2021.

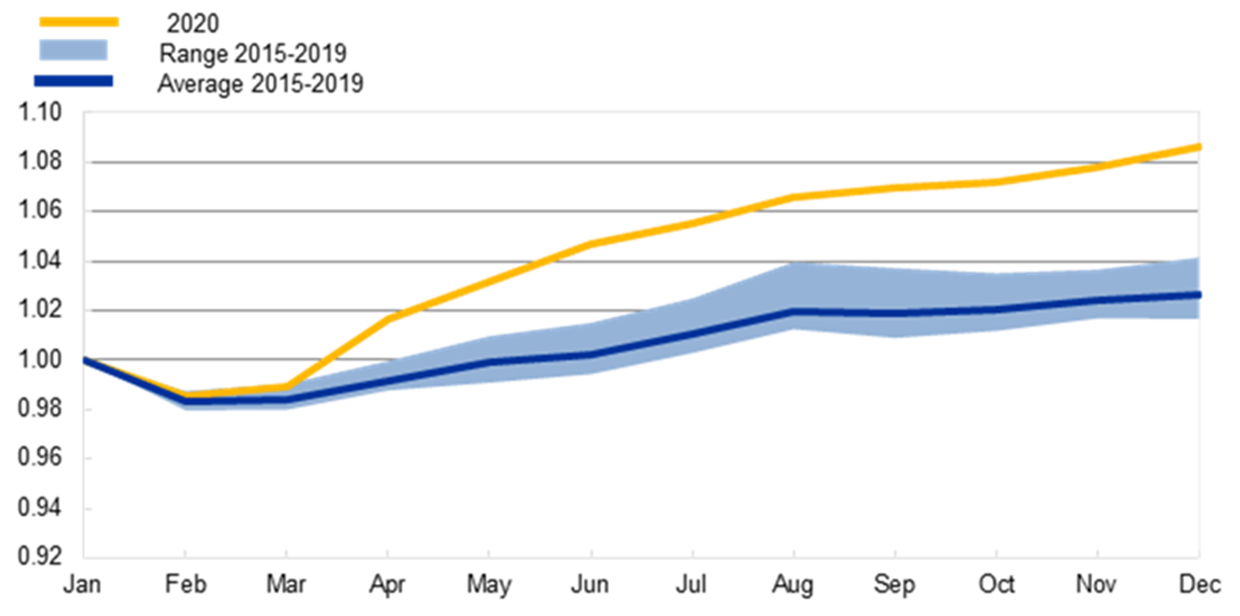

To put this in perspective, if we compare issuance volumes in the spring of 2020 with the average volumes of the previous five years, up to 4% more euros were issued. The second phase of lockdowns triggered likewise strong banknote demand, with the difference from the expected growth path rising further to 8% by the end of 2020 (Chart 3).

Chart 3

Total value of banknote circulation in 2020 compared with the previous five (non-crisis) years (2015-19)

(index, January=1)

Source: ECB.

One possible explanation for this apparent paradox – increasing demand for banknotes while cash payments decline – is that during the crisis people turned to cash as a tool to manage uncertainty. Research shows that at the beginning of the pandemic, consumers – especially those with low income – cut spending and increased their holdings of liquid assets.[5] And cash is the most liquid asset for those looking to satisfy their heightened liquidity preference.

Pre-crisis trends in the use of banknotes also point to the role of cash as a store of value as much as a means of payment. Recent estimates suggest that, before the pandemic, only around 20% of the overall amount of euro banknotes in circulation were actively used for transaction purposes within the euro area (Chart 4).[6] The vast majority of cash, around one trillion euro, is held as an asset and used only sporadically for payments, or is circulating outside the euro area.

Chart 4

Estimates of components of euro banknote circulation for 2019

(percentages, rounded figures without decimals)

Source: Zamora-Pérez.

The store of value function guarantees a persistent level of demand for banknotes even as digital payments take off.

And cash also has unique features which underpin its demand. For example, it is often the only way to guarantee financial inclusion, as it allows users to make payments at no cost. In the euro area, there are 13.5 million adults who are unbanked[7] and rely mostly on cash.[8]

Cash allows almost anyone – including older people, the partially sighted and people with disabilities – to check that the money they are using is genuine.[9] And it has a role to play in financial education, as children under the age of 15 use notes and coins when paying for things out of their pocket money.

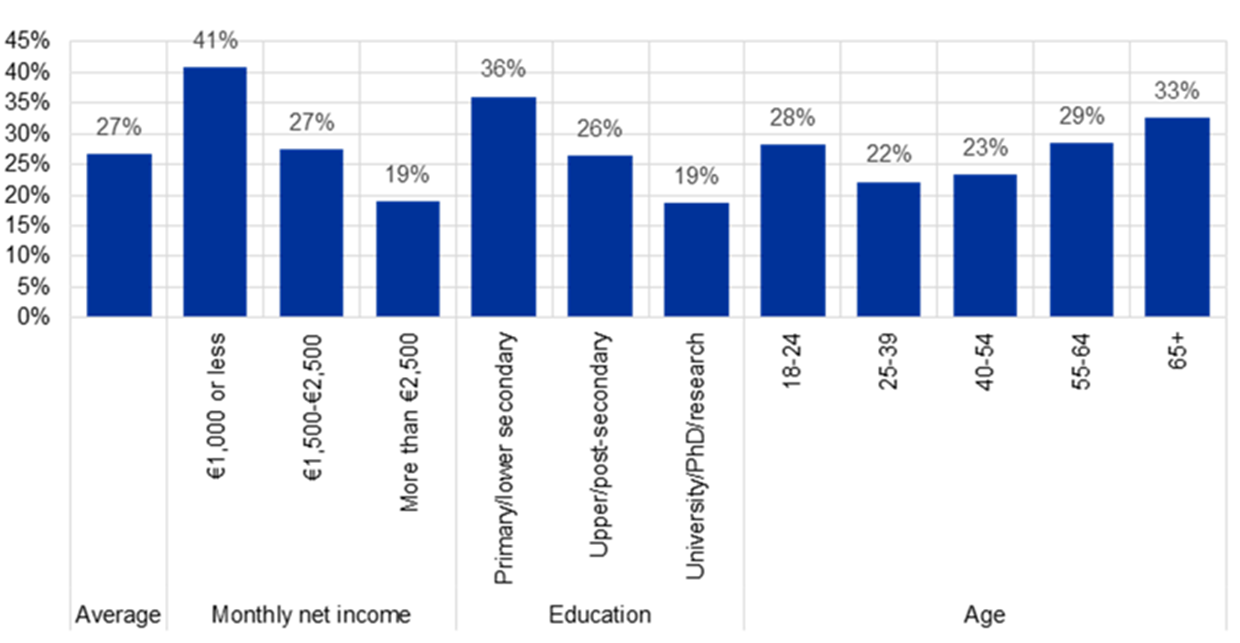

Evidence suggests that without cash, both merchants and consumers, particularly those with low income, would be significantly worse off.[10] This may also be the case for other segments of the population, such as older people or those with a lower level of education, who report preferring cash over other means of payment (Chart 5). And the private costs of restricting access to cash seem to be much greater than the social benefits of curbing cash-related illegal activities.[11] To address concerns about such activities[12], the Eurosystem no longer issues the largest euro banknote denomination.[13]

Chart 5

Self-reported preference for cash in the euro area

Share of respondents reporting a preference for cash, by socio-demographic group

(percentages)

Sources: Study on the payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area (SPACE) (2019), De Nederlandsche Bank and the Dutch Payments Association (2019) and Deutsche Bundesbank (2019).

Notes: The question included the following answer options: “Cash”, “Cards”, “Don’t know” and “I don’t have a clear preference between cash and cards”. Net income is not adjusted for the cost of living. For respondents in the Netherlands, net income was estimated from annual gross income.

Consumers also legitimately value privacy when making payments, which is best provided by cash.[14] As the digital economy grows, consumers are increasingly concerned about how their data are collected and used.[15]

Last but not least, euro banknotes and coins are the face of the European construction. They are the most tangible and visible symbol of European integration.

The future of cash

Given its many functions, I expect cash to survive the digital revolution and that people will continue to use it for many years to come.

But cash could be under threat if, for example, retailers stop accepting it at points of sale. It is therefore vital that we protect the role of cash as both a means of payment and a store of value. For this reason, the Governing Council adopted the Eurosystem’s Cash 2030 Strategy in September last year.

We have four key strategic goals in this respect. The first is to continue providing an efficient and robust supply of cash. This reflects our responsibility under the EU Treaty to satisfy any demand for euro banknotes, in any situation and for any amount.

The second goal is to ensure that euro banknotes and coins continue to be universally accepted by merchants and available to consumers as part of the basket of payment instruments.

The third goal is to continue providing safe, state-of-the-art euro banknotes, recognising their role as a powerful symbol of European integration. As part of our strategy, we will engage with the public to understand which themes and designs can best connect us through euro banknotes in the future.

Finally, we plan to assess and reduce the environmental footprint of cash via new products and processes. Central to this goal is our target to use 100% sustainable cotton for banknotes and the landfill ban for banknote waste.

To achieve these goals we are cooperating with a range of stakeholders and taking several concrete measures. Last year, the Euro Retail Payments Board (ERPB) – which I chair as a representative of the ECB – decided to set up a dedicated working group to analyse the adequacy of cash services and to preserve cash infrastructure in the euro area.[16] This group brings together central banks, bank and non-bank intermediaries, retailers and consumer associations and will provide a report in the autumn.

We are also supporting the European Commission in exploring the need for a review of its 2010 Recommendation on the scope and effects of legal tender of euro banknotes and coins and for new regulatory measures to ensure adequate cash services across the euro area.

These measures reflect the Eurosystem’s commitment to safeguarding cash and its role as a payment instrument. This commitment can also be seen in our ongoing reflections on the potential launch of a digital euro.

We have made it clear that a digital euro would be a complement to cash, not a replacement. Both are important for our aim of providing safe money as a public good and preserving the role of sovereign money at the heart of the financial system. In fact, a clear message from our recent public consultation was that most respondents were willing to support a digital euro, but only on the condition that the Eurosystem maintained its commitment not to use a digital euro to discontinue cash.[17]

We are also learning from our experience with cash. Cash forms the basis of Europeans’ expectations of central bank money. Accordingly, the digital euro should be widely accessible, inclusive, and respectful of privacy. It is also expected to be legal tender, while fully respecting the legal tender status of cash.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

The world is changing fast. But the Eurosystem will ensure that in the digital era all Europeans will continue to have cost-free access to safe, sovereign money that respects privacy and has legal tender status, ensuring it can be used everywhere.

Our commitment to both the physical and the digital euro will strengthen the role of public money in the euro area, making it fit for the digital age while ensuring that cash will continue to meet the needs of Europeans.

- See McKinsey & Company (2020), “How COVID-19 has pushed companies over the technology tipping point—and transformed business forever”, October.

- See “Study on the payment attitudes of consumers in the euro area (SPACE)”, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, December 2020.

- ibid.

- See Panetta, F. (2020), “Beyond monetary policy – protecting the continuity and safety of payments during the coronavirus crisis”, The ECB Blog, April; and Tamele, B., Zamora-Pérez, A., Litardi, C., Howes, J., Steinmann, E. and Todt, D., “Catch me (if you can) - assessing the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection via euro cash”, Occasional Paper Series, ECB, forthcoming.

- See Cox, N. et al. (2020), “Initial impacts of the pandemic on consumer behavior: Evidence from linked income, spending, and savings data”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Summer 2020 special edition.

- See Zamora-Pérez, A. (2021), “The paradox of banknotes: understanding the demand for cash beyond transactional use”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB, Frankfurt am Main.

- Persons aged 15+. See World Bank (2018), “The Little Data Book on Financial Inclusion 2018”, World Bank, Washington, D.C.

- While some unbanked adults may rely on a member of their household to use electronic payment instruments that need a bank account, this limits their independent access to financial resources and further increases the importance of cash to them.

- Euro banknotes have embedded visual and haptic security features.

- Alvarez, F. and Argente, D. (2020), “Consumer surplus of alternative payment methods: paying Uber with cash”, NBER Working Paper Series, No 28133, November.

- Alvarez, F., Argente, D., Jimenez, T. and Lippi, F. (2021), “Cash: a blessing or a curse”, mimeo.

- Rogoff, K. (2016), The curse of cash, Princeton University Press.

- The ECB discontinued the production and issuance of €500 banknotes in 2019, although existing €500 banknotes are still legal tender and can therefore continue to be used and will always retain their value.

- Kahn, C. M., McAndrews, J. and Roberds, W. (2005), “Money is Privacy”, International Economic Review, Vol. 46, No 2, May, pp. 377-399.

- Acquisiti, A., Taylor, C. and Wagman, L. (2016), “The economics of privacy”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 54, No 2, June, pp. 442-492.

- See “Mandate of the ERPB working group on access and acceptance of cash”.

- See ECB (2021), “Eurosystem report on the public consultation on a digital euro”, April.

European Central Bank

Directorate General Communications

- Sonnemannstrasse 20

- 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

- +49 69 1344 7455

- media@ecb.europa.eu

Reproduction is permitted provided that the source is acknowledged.

Media contacts