Foreword

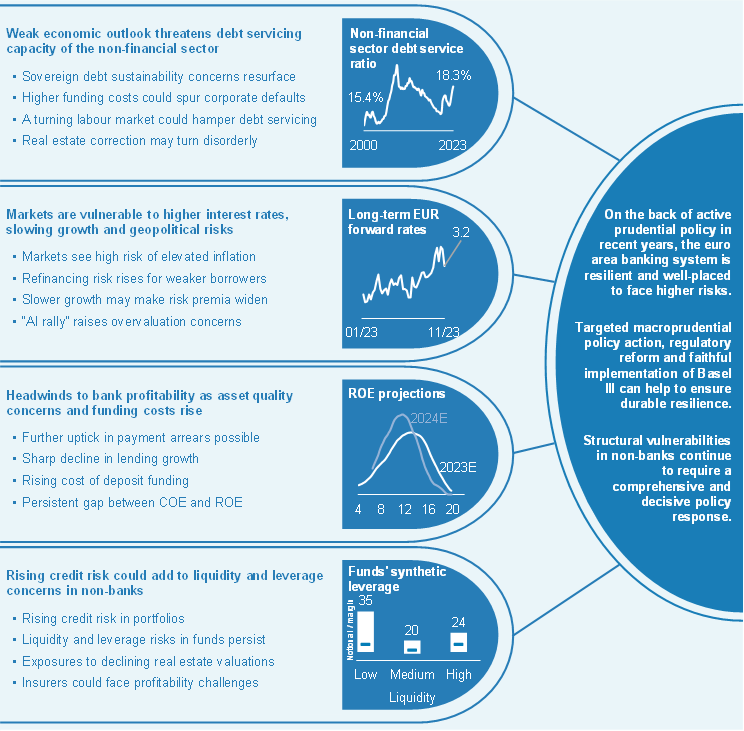

The turbulence seen this last spring, triggered by bank failures outside the euro area, has now abated. While risks to financial stability may appear less acute, they remain elevated. Attention has shifted towards the impact of tight financial and credit conditions and weak economic prospects on the debt servicing capacity of borrowers, the ongoing correction in real estate markets and the resulting risks for banks and non-bank financial intermediaries.

While tight financing conditions help align aggregate demand with supply and ensure that inflation returns to target, they can also push over-extended borrowers into financial distress. Steep increases in interest rates are particularly challenging for borrowers carrying high levels of debt contracted at variable rates or loans that fall due for refinancing in the near term. Disposable incomes, corporate revenues and fiscal positions may suffer an additional squeeze if economic activity disappoints further or if energy prices surge over the coming winter.

Despite such risks, financial markets have remained resilient. This strength reflects expectations of a soft landing, with limited impacts on economic growth as inflation recedes to moderate levels. Sentiment could shift quickly if actual outturns were to deviate from this benign scenario, and disorderly adjustments could be amplified by non-bank financial institutions with elevated credit and liquidity risks. An escalation of the conflict in the Middle East could trigger a sharp increase in risk aversion in financial markets, unravelling the prevailing vulnerabilities. In addition to the potential adverse repercussions for the supply of energy commodities, an escalation could undermine general confidence and slow down economic growth, while pushing inflation rates up in parallel.

Although their lending margins have until now largely benefited from rising interest rates, banks are beginning to face increasing headwinds. Demand for loans is cooling exceptionally quickly and loan losses are starting to rise, albeit from low levels. The ongoing correction in real estate markets – both commercial and residential – may compound these dynamics.

This issue of the Financial Stability Review (FSR) includes two special features. The first examines different strategies employed by euro area banks to manage interest rate risk and the associated implications for bank profitability. The second looks at risks to euro area real estate markets in a turning property market cycle.

The FSR has been prepared with the involvement of the ESCB Financial Stability Committee, which assists the decision-making bodies of the ECB in the fulfilment of their tasks. The FSR promotes awareness of systemic risks among policymakers, the financial industry and the public at large, with the ultimate goal of promoting financial stability.

Luis de Guindos

Vice-President of the European Central Bank

Overview

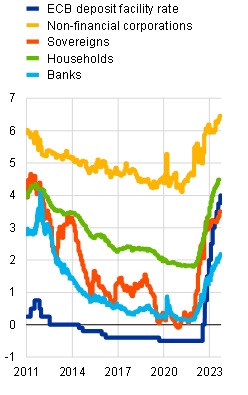

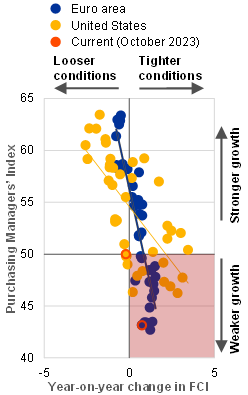

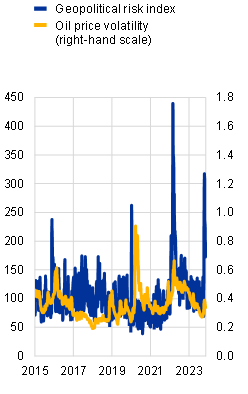

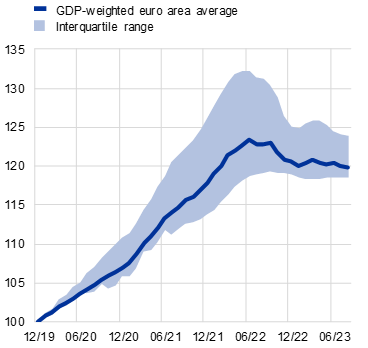

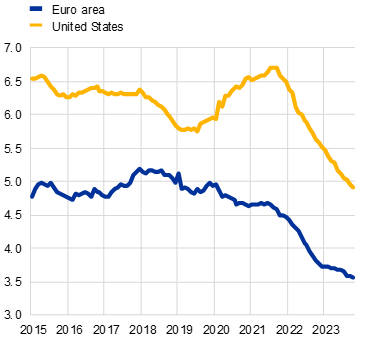

Euro area financial stability outlook remains fragile

Financial stability risks associated with higher interest rates are emerging in the context of a challenging macro-financial outlook and geopolitical tensions. Financial markets quickly shook off the shock triggered by the bank failures in the United States and Switzerland in March this year and the related expectations of an earlier end to the monetary tightening cycle. Since then, financial stability concerns have pivoted towards the implications of upside risks to inflation and downside risks to growth. Rising ECB policy rates have translated into rising funding costs for all sectors of the economy (Chart 1, panel a). The associated tighter financial and credit conditions are being transmitted to economic activity (Chart 1, panel b). This holds particularly true for the euro area where – unlike the United States – economic outcomes have surprised on the downside since the summer. However, as duration lengthened in the financial system and the real economy during the low interest rate era, a major part of the impact of monetary tightening is yet to materialise, which will pose future challenges for financial and non-financial sectors alike. These concerns are amplified by the recent flare-up of geopolitical tensions in the Middle East. They add to the uncertainty surrounding the macro-financial outlook (Chart 1, panel c), not only because of possible adverse repercussions for energy commodities supply, should the conflict escalate further, but also given their potential to spark risk aversion in financial markets and undermine confidence in the real economy.

Chart 1

Euro area financial stability outlook remains fragile as tighter financing conditions are increasingly propagating to the real economy and geopolitical tensions intensify

a) Composite funding costs, by economic sector | b) Financial conditions index and manufacturing PMIs | c) Geopolitical risk index and oil price volatility |

|---|---|---|

(Jan. 2011-Sep. 2023, percentages) | (July 2020-Oct. 2023; diffusion index, percentages) | (1 Jan. 2015-14 Nov. 2023; index, percentages, 7-day moving averages) |

|  |  |

Sources: Caldara and Iacoviello*, Bloomberg Finance L.P., S&P Global Market Intelligence, ECB (MIR, PDF) and ECB calculations.

Note: Panel a: Non-financial corporations: weighted average of the costs of bank borrowing, market-based debt and equity, based on the respective amounts outstanding. Sovereigns: ten-year government benchmark bond yield. Households: lending rates for new loans for house purchase, consumer credit and other household loans weighted by their respective outstanding credit amounts. Banks: volume weighted average of the cost for banks of collecting deposits and the cost for banks of issuing bonds, weighted by the respective outstanding amounts. . Panel b: Goldman Sachs’ financial conditions index (FCI) is a weighted average of risk-free interest rates, exchange rates, equity valuations and credit spreads, with weights corresponding to the direct impact of each variable on GDP.

*) Caldara, D. and Iacoviello, M., “Measuring Geopolitical Risk”, American Economic Review, Vol. 112, No 4, April 2022, pp. 1194-1225.

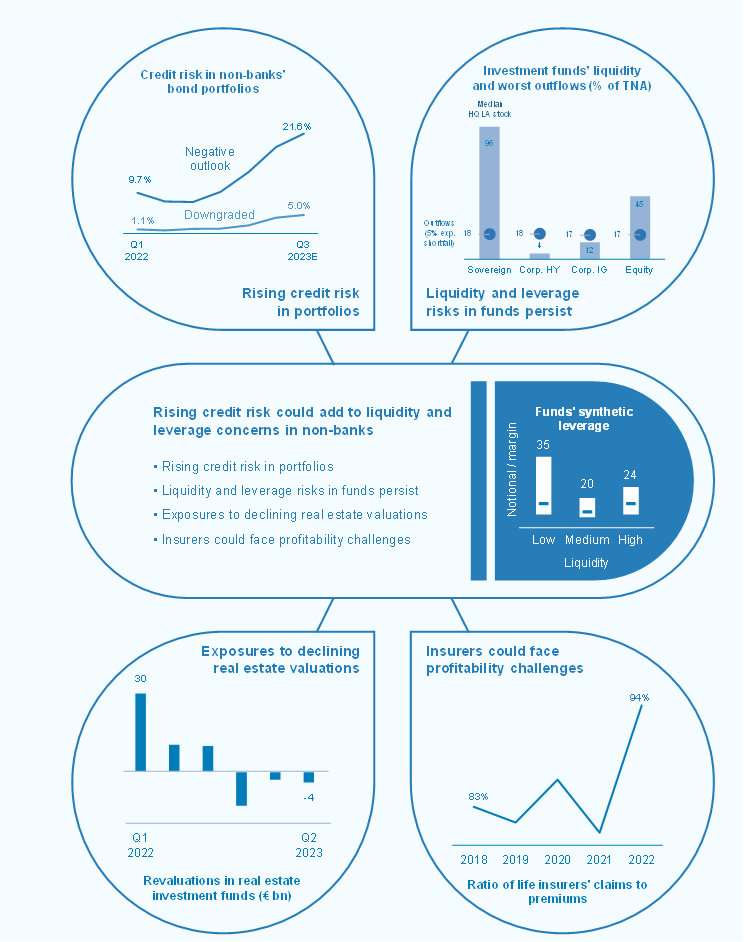

Against this backdrop, three key themes shape the outlook for euro area financial stability. First, markets and non-banks remain highly vulnerable to adverse macro-financial and geopolitical surprises and associated shifts in market sentiment. Second, tighter financial and credit conditions are increasingly translating into higher debt service costs, weakening the resilience of firms, households and sovereigns. Third, growing vulnerabilities in the real economy can be expected to gradually impair banks’ asset quality, and this, together with lower lending volumes and rising funding costs, may challenge their profitability outlook.

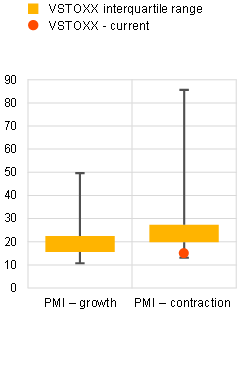

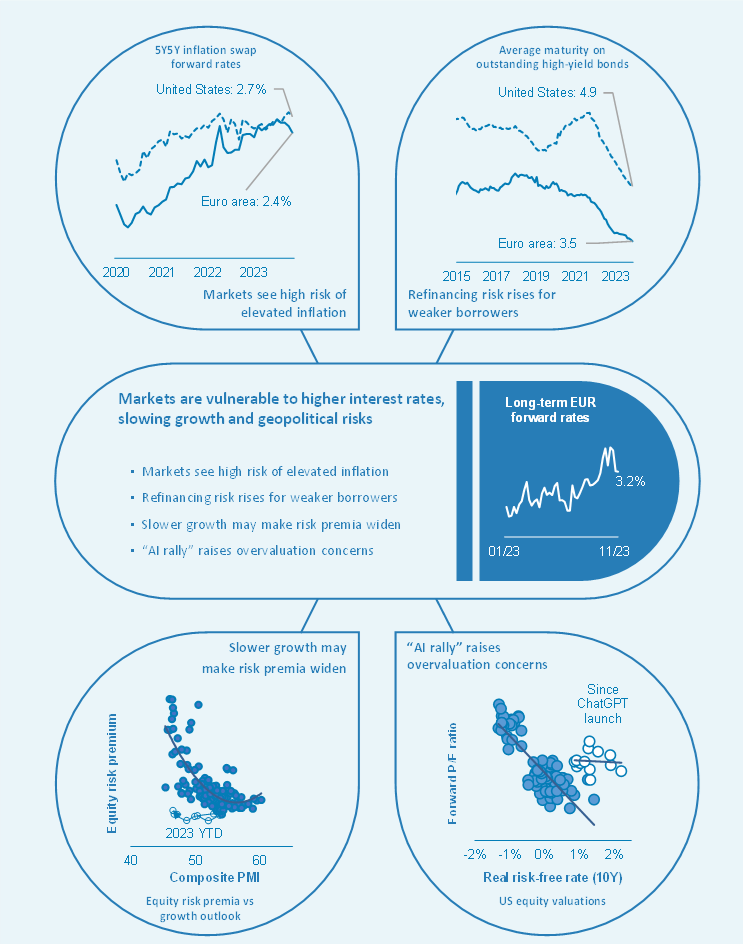

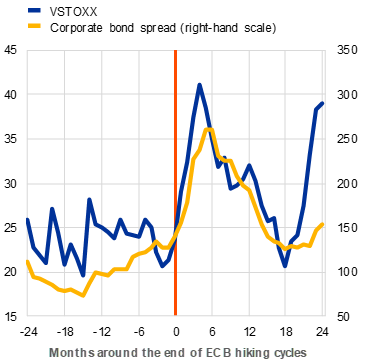

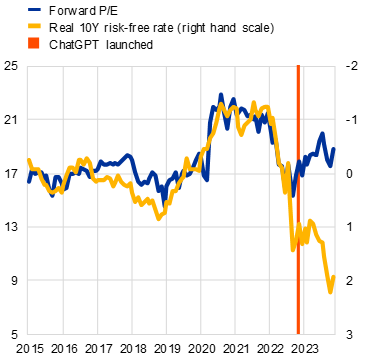

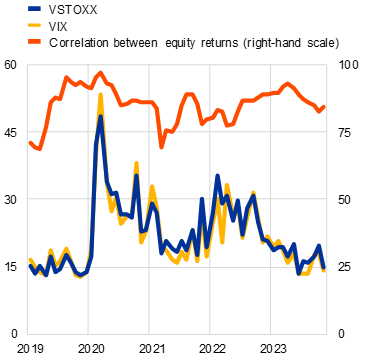

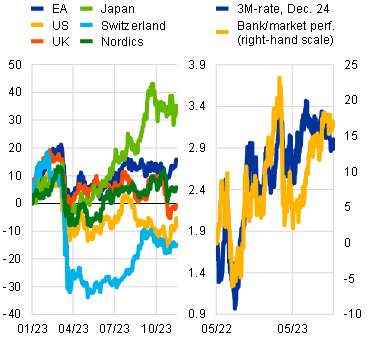

Financial markets and non-banks are vulnerable to adverse macro-financial surprises

The pricing in financial markets appears to be predicated on optimistic expectations regarding the future macro-financial outlook and hence remains vulnerable to negative surprises. Up until August, expectations that the monetary tightening cycle was nearing its end, with a soft-landing scenario for economic growth and inflation, served to lower market volatility and support investor sentiment (Section 2.1). Global equity markets performed particularly strongly after the turmoil triggered by stresses in the US and Swiss banking sectors in March (Chart 2, panel a) – albeit driven to a large extent by a US tech industry that has benefited from enthusiasm regarding the opportunities offered by artificial intelligence (Section 2.3). In the euro area equity market, volatility has been out of sync with the current weak phase of the economic cycle (Chart 2, panel b). At the same time, corporate credit spreads have remained relatively compressed, while liquidity conditions in sovereign and corporate bond markets have improved. In September, the transition of financial markets towards expectations of higher-for-longer rates gained momentum and was accompanied by rising term premia. This led to a rapid increase in long-term government bond yields and higher equity market volatility, which started to weigh on riskier asset valuations as well. However, the market correction proved to be short-lived, as investor confidence benefited again from a downside surprise in inflation.

Risk sentiment in the markets remains fragile and highly sensitive to further surprises regarding the outlook for inflation, growth and, by extension, the path of monetary policy. If inflation were to prove more persistent than currently anticipated, this could lead to a further increase in long-term interest rates. Coupled with weaker than anticipated economic growth, this, in turn, could trigger a rise in market volatility and risk premia, increasing the likelihood of credit events materialising. Adverse market dynamics could be triggered by unexpected geopolitical shocks and amplified by vulnerabilities associated with the increased digitalisation of financial services (Box 3), heightened leverage in equity option markets (Box 2) and possible forced asset sales by non-bank financial institutions.

Chart 2

Investor optimism leaves markets vulnerable to disorderly repricing, especially if volatility jumps and funds with low liquidity buffers are forced to sell assets

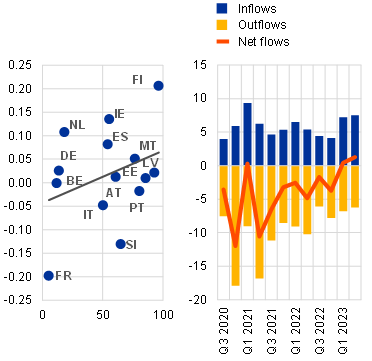

a) Global equity and bond market prices | b) Distribution of VSTOXX, by PMI signal | c) Distribution of funds’ HQLA stock and historically high outflows |

|---|---|---|

(1 Jan. 2022-14 Nov. 2023, indices) | (2 Jan. 2012-14 Nov. 2023, index) | (Q2 2023 (HQLA), Jan. 2007-June 2023 (outflows), percentages of total net assets) |

|  |  |

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., S&P Global Market Intelligence, LSEG Lipper IM, ECB (CSDB) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: global equity markets are reflected by the MSCI All Country World Index and global bond markets by the Bloomberg Barclays Multiverse Index. Panel b: based on Composite PMI with readings above 50 indicating growth. The whiskers correspond to the minimum and maximum values observed. Panel c: the box plots show the distribution of fund-level stocks of high-quality liquidity assets (HQLA), calculated according to the Basel Liquidity Coverage Ratio Requirements for HQLA. Whiskers refer to the 5th and 95th percentiles of the distribution respectively. HQLA Level 1 assets include cash, cash equivalents and qualifying government bonds, while Level 2A and Level 2B assets include less liquid assets such as qualifying covered bonds, corporate bonds, asset-backed securities and equities. The stock of HQLA is calculated by applying a haircut of 0% to cash and Level 1 assets, 15% to Level 2A assets and 40% to Level 2B assets. The red dots show the worst outflows for each fund category – calibrated in line with ESMA’s stress simulation for investment funds* – as the 5% expected shortfall, which averages monthly fund-level net flows experienced between January 2007 and June 2023 by a sample of bond and equity funds below the 5th percentile of the distribution. AE stands for advanced economies; EME stands for emerging market economies; HY stands for high yield; IG stands for investment grade.

*) See ESMA, “Stress simulation for investment funds”, ESMA Investment Report, 2019.

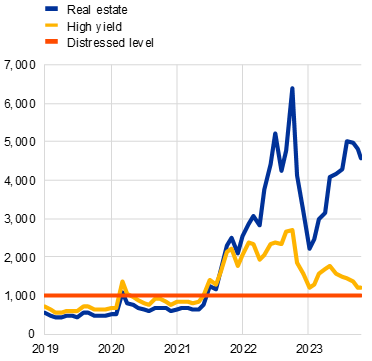

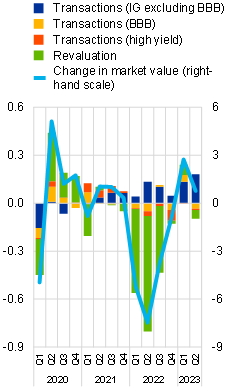

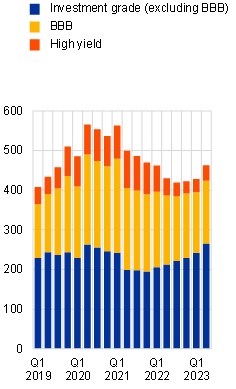

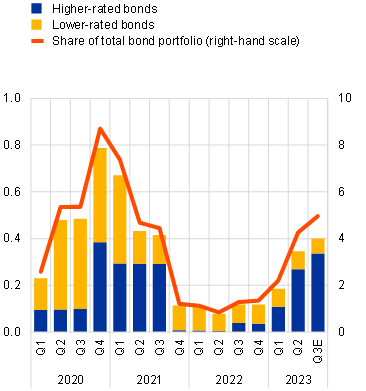

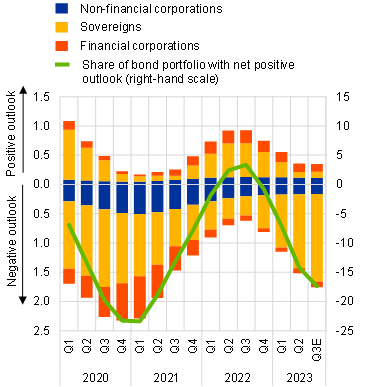

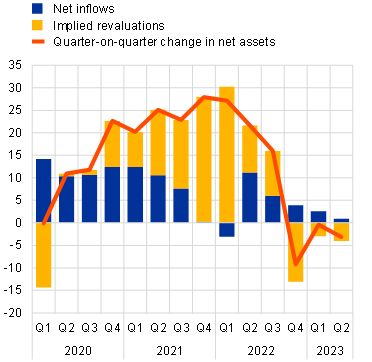

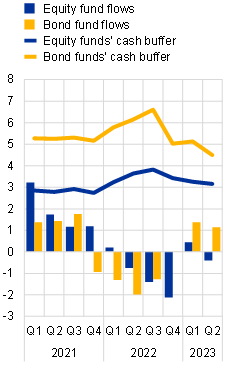

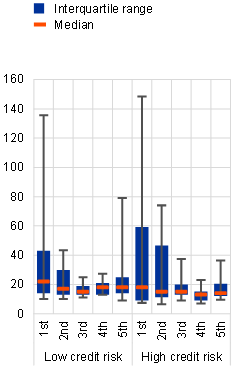

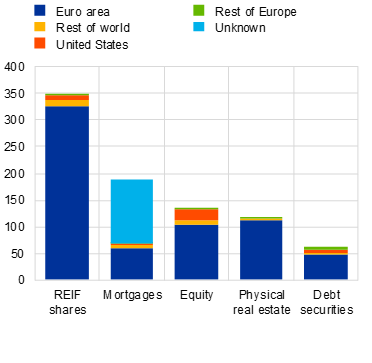

Non-banks continue to face high credit risks, despite some rebalancing of their investment portfolios towards safer assets. As of mid-2023 cumulative purchases of investment-grade sovereign and corporate debt by the non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI) sector over one year have been close to the record highs observed during the post-pandemic recovery (Section 4.1). Shifts by investors towards safer fund types helped mitigate aggregate credit risk in the sector thanks to reduced incentives to search for yield. That said, high economic uncertainty and tighter financial conditions have contributed to a deteriorating credit outlook for several issuers, exposing the NBFI sector to possible revaluation losses stemming from downgrades and an increase in default risk. In particular, some non-banks remain heavily exposed to interest rate-sensitive sectors, such as highly indebted corporates and real estate. Deteriorating corporate fundamentals and the ongoing correction in real estate markets could expose non-banks investing in these sectors to revaluation losses and investor outflows.

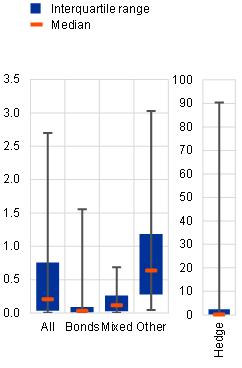

Low liquid asset holdings could expose investment funds to the potential risk of forced asset sales if macro-financial outcomes deteriorate. Overall liquidity buffers remain relatively low across the investment fund sector (Section 4.2), although aggregate figures mask large differences across and within fund types. This suggests that there is a more vulnerable cohort of funds with inadequate liquidity buffers to meet a redemption shock equivalent in size to the worst recorded outflows (Chart 2, panel c). As such, the risk remains high that, in the event of sudden liquidity needs, some funds could amplify adverse market dynamics by exhibiting procyclical selling behaviour. Granular fund-level data on open-ended bond funds suggest that their liquidity resilience to severe redemptions has deteriorated compared with levels observed before the pandemic (Box 6). This could introduce risks to wider financial stability, especially when low liquidity buffers coincide with relatively high leverage (Section 4.2). All in all, this highlights the importance of strengthening the resilience of the NBFI sector from a macroprudential perspective (Chapter 5).

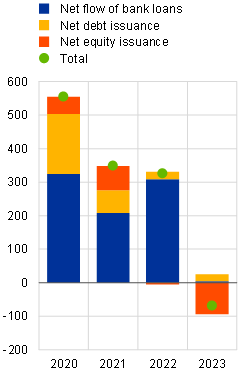

Tighter financial conditions are testing the resilience of euro area firms, households and sovereigns

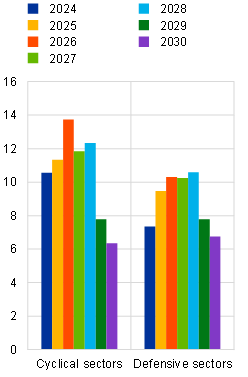

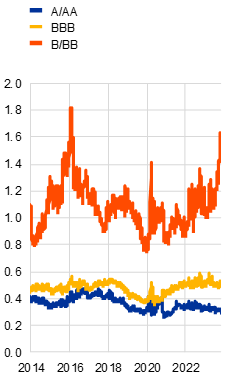

Euro area corporate profitability has held up well, but higher interest rates are weighing on the debt servicing capacity of more vulnerable firms. High profit margins have continued to underpin corporate profitability, but activity has been slowing in several sectors (Section 1.3). Tighter financing conditions, in terms of both the cost and the availability of credit, coupled with the uncertain business outlook, have led to a material drop in firms’ external financing (Chart 3, panel a). As the stock of loans continues to reprice, higher debt service costs could challenge cyclical sectors more than defensive sectors. The redemption profiles show that cyclical sectors are generally more exposed to refinancing risk, as a larger share of their bonds matures in the short term (Chart 3, panel b). Rollover risk might be further accentuated if the economy were to weaken at the same time. Weaker macro-financial conditions have already started to translate into higher corporate insolvencies: in aggregate, these have now surpassed pre-pandemic levels, albeit unevenly across sectors. While this partly reflects the unwinding of the insolvency backlog that accumulated during the pandemic, defaults are likely to rise even more if yields continue increasing or if energy prices start soaring again, for example. This is already reflected in rising expected default frequencies, in particular for the more vulnerable high-yield segment (Chart 3, panel c). Looking ahead, a sharper economic slowdown than currently anticipated could prove challenging for euro area firms, especially if they have high debt levels, subdued earnings and low interest coverage ratios.

Chart 3

Tighter financial conditions are increasingly challenging the debt servicing capacity of firms, given high short-term debt servicing needs and rising corporate insolvencies

a) Financing flows of non-financial corporations, by funding instrument | b) Maturity wall for euro area non-financial firms, by type of industry | c) Corporate EDFs in the euro area, by rating category |

|---|---|---|

(Q1 2020-Q3 2023, € billions) | (2024-30, percentages) | (1 Jan. 2014-14 Nov. 2023, percentages) |

|  |  |

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Moody's Analytics, Intercontinental Exchange, ECB (BSI, CSEC) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel b: figures include corporate bonds that are not in default and are issued by euro area entities. Cyclical sectors include consumer discretionary, technologies, energy, materials, industrials and communications. Defensive sectors include consumer staples, health care and utilities. Panel c: EDFs stands for the expected default frequencies of non-financial corporations.

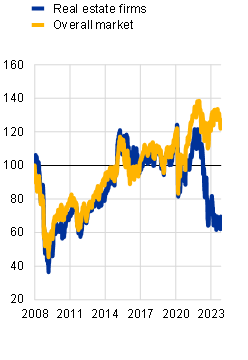

Real estate firms are particularly vulnerable to losses in the light of the ongoing downturn in euro area commercial real estate markets. In an environment of tighter financing conditions and elevated macro-financial uncertainty, commercial real estate (CRE) prices have continued to decline (Chart 4, panel a), with subdued market activity hampering price discovery. The effects of higher interest rates have been compounded by structurally lower demand for some CRE assets following the pandemic. In fact, demand for office space deteriorated sharply in the second quarter of 2023, particularly in the non-prime segment where concerns about the environmental footprint of buildings play a more important role. This mix of cyclical and structural challenges has resulted in real estate firms suffering significant rating downgrades in recent months (Section 1.5). Conditions have been particularly challenging for property developers faced with falling sales prices, contracting order books and rising input costs. As such, the stock prices of real estate firms have continued to underperform the overall market by a large margin (Chart 4, panel b). From a systemic risk perspective, adverse CRE market outcomes on their own are unlikely to cause losses that would take the euro area banking sector below minimum capital requirements, but a significant deterioration in CRE asset quality could pose challenges for some banks that are more heavily exposed to CRE loans (Special Feature B).

Euro area households, especially those with lower incomes and in countries with mainly floating-rate lending, are increasingly being challenged by higher interest rates. Resilient labour markets as well as government support measures and excess savings accumulated during the pandemic have so far mitigated euro area household vulnerabilities. However, real household incomes and consumption remain under pressure, especially in the lower income segments. At the same time, higher interest rates have begun to feed through to higher debt service costs, notably in countries where the share of variable-rate lending has historically been very high (Section 1.4). Going forward, households may see their debt servicing capacity erode if energy prices soar again, interest rates remain higher for longer and/or labour market conditions deteriorate significantly.

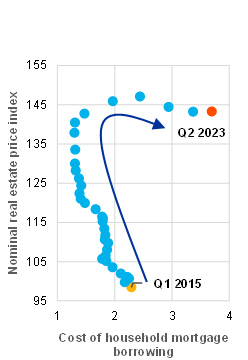

Chart 4

Residential and commercial real estate markets have continued their simultaneous downturn, as higher funding costs weigh on affordability

a) Euro area real GDP growth, and RRE and CRE prices | b) Stock prices of real estate firms versus the overall market | c) Real estate price index and cost of household mortgage borrowing in the euro area |

|---|---|---|

(Q1 2006-Q2 2023, annual percentage changes) | (4 Jan. 2008-10 Nov. 2023, indices: | (Q1 2015-Q2 2023, percentages, index) |

|  |  |

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Eurostat and ECB (MNA), ECB (MIR, RESC) and ECB calculations.

Note: Panel b: real estate firms are represented by the STOXX Europe 600 Real Estate Price and the overall market by the STOXX Europe 600.

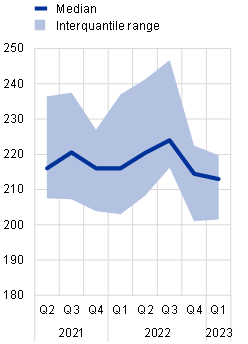

The ongoing correction in residential real estate (RRE) markets may compound pre-existing vulnerabilities of euro area households. Euro area RRE markets continued to cool in the first half of 2023 (Chart 4, panel a), with prices already starting to fall in a number of countries. The steep increase in borrowing costs, coupled with deteriorating consumer confidence and housing market prospects, has had a negative impact on the demand for mortgages. This, together with a substantial tightening of credit standards by banks, led to a sharp drop in new lending (Section 1.5). On the supply side, challenging housing market conditions are reflected in weak construction confidence and a sharp drop in the issuance of new residential building permits. Despite declining prices in some euro area countries, valuations still seem stretched, suggesting that further falls are possible. In particular, RRE markets could come under severe stress should a material weakening of the labour market add to the affordability challenges arising from tighter conditions in mortgage markets (Chart 4, panel c, Special Feature B).

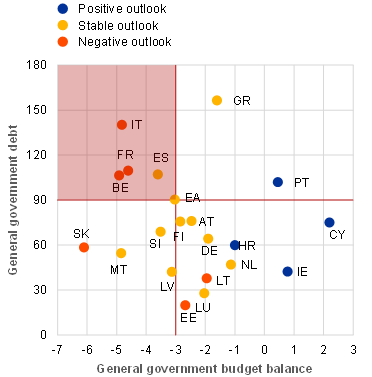

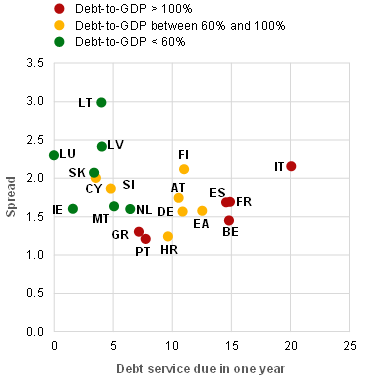

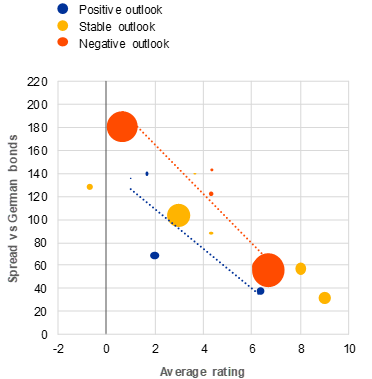

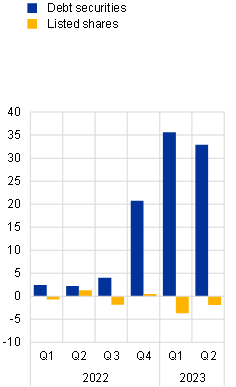

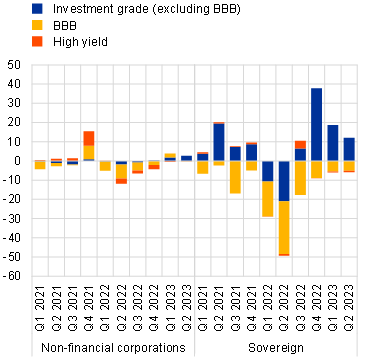

Medium-term sovereign vulnerabilities are rising, particularly for jurisdictions where debt levels are already high. With maturing public debt being rolled over at higher interest rates, sovereign interest payments have started to rise, mainly in countries where short-term refinancing needs are higher. Sovereign issuance activity in primary markets has remained brisk this year (Chart 5, panel a). Increased issuance by euro area sovereigns has been smoothly absorbed by the market despite reduced Eurosystem asset purchases as a result of quantitative tightening. Demand might have been supported by the higher yields offered by sovereign bonds (Box 1). Nevertheless, fiscal fundamentals remain fragile in a number of countries in the light of weaker economic growth prospects, given elevated debt levels and continued high budget deficits (Chart 5, panel b). So far, spreads in the government bond market have remained contained, as many sovereigns managed to secure cheap financing at longer maturities during the period of low interest rates. However, risks of fiscal slippage could reignite sovereign debt sustainability concerns and compel market participants to reassess sovereign risk. Any unwarranted, disorderly sovereign debt market dynamics that may pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area can be countered by the ECB’s Transmission Protection Instrument if the necessary conditions are fulfilled.

Chart 5

Short-term sovereign stress has remained contained so far, but higher funding costs and less prudent fiscal policies could reignite sovereign debt sustainability concerns

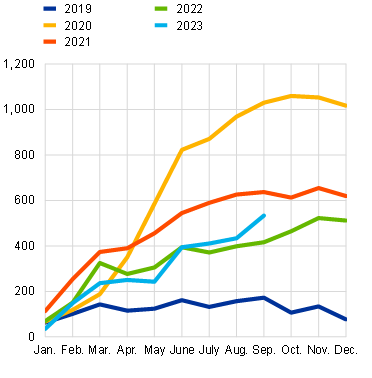

a) Net issuance of government debt securities in the euro area | b) General government debt, budget balance and rating outlooks across the euro area |

|---|---|

(Jan. 2019-Sep. 2023, € billions) | (average values over 2023-24, percentages of GDP) |

|

|

Sources: ECB (GFS), Moody’s Analytics, Fitch Ratings, S&P Global Market Intelligence, European Commission (AMECO) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel b: rating outlook refers to the average from Moody’s Analytics, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch and represents the outlook as at 14 November 2023. The vertical red line represents the Maastricht government deficit criterion of 3% of GDP. The horizontal red line represents the threshold of 90% of GDP for sovereign debt and is based on findings in the empirical literature. See, for example, Checherita, C. and Rother, P., “The impact of high and growing government debt on economic growth – an empirical investigation for the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 1237, ECB, 2010.

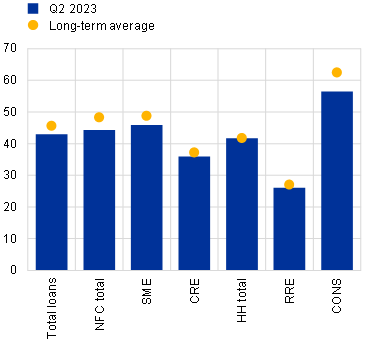

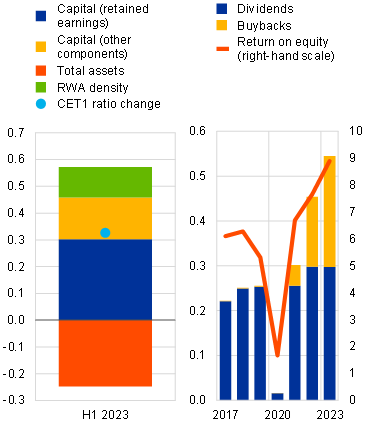

Higher rates underpin bank profitability, but worsening asset quality and higher funding costs pose headwinds

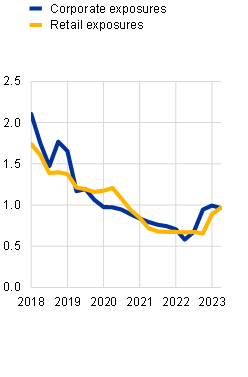

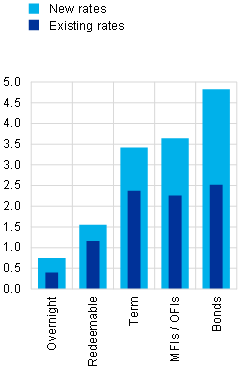

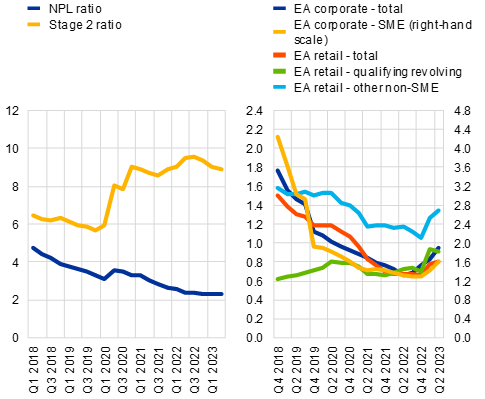

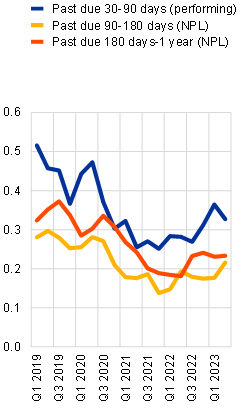

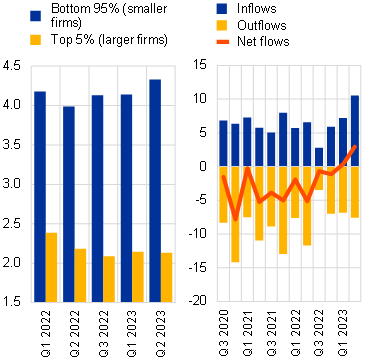

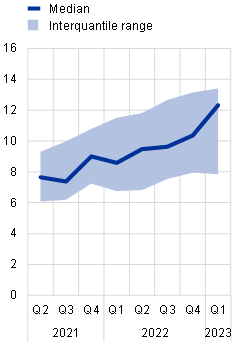

Euro area banks’ profitability has continued to improve on the back of rising interest rates, but uncertainties around the earnings outlook have increased. Boosted mainly by wider interest margins, euro area banks continued to enjoy robust earnings growth in the first half of 2023. They posted the highest profitability levels witnessed in more than a decade, with an almost double-digit return on equity (Chart 6, panel a). The strengthening of profitability was particularly notable for banks in countries where variable-rate lending predominates and where the pass-through of higher policy rates to deposit costs has been slower (Chapter 3). Going forward, though, banks will increasingly feel the downside impact of higher interest rates, as tighter financing conditions and a higher cost of living adversely affect borrowers’ debt servicing capacity. While banks’ non-performing loan ratios remained broadly unchanged at a low level of just above 2% in the first half of 2023, there have been some nascent signs of rising losses on some loan portfolios that are more sensitive to cyclical downturns. In fact, default rates on both corporate and retail exposures have already started picking up (Chart 6, panel b), heralding further increases in non-performing loans. As such, banks may face the risk of higher provisioning costs as risks in the non-financial sectors materialise in the context of weaker than anticipated economic conditions, potentially higher-for-longer interest rates or possible disorderly developments in real estate markets.

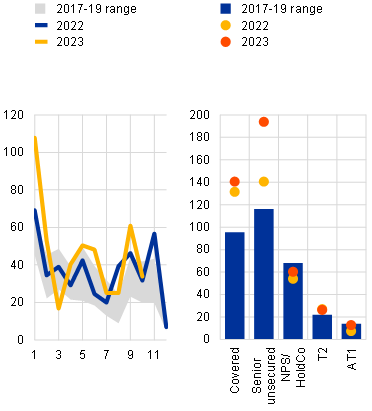

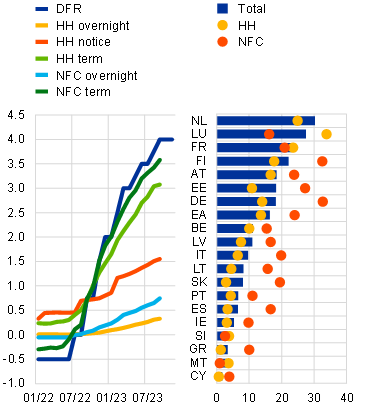

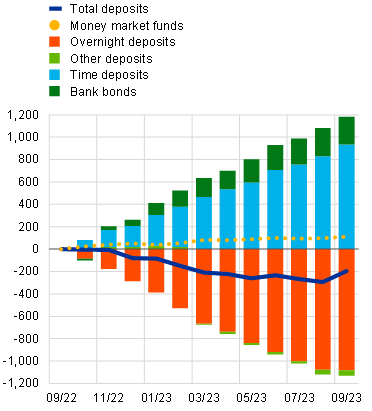

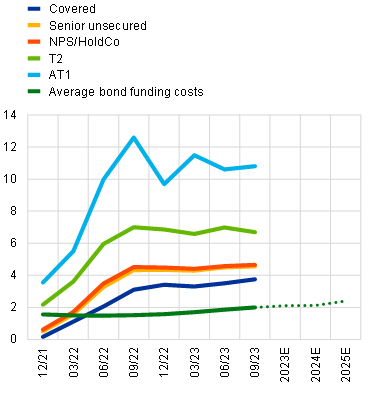

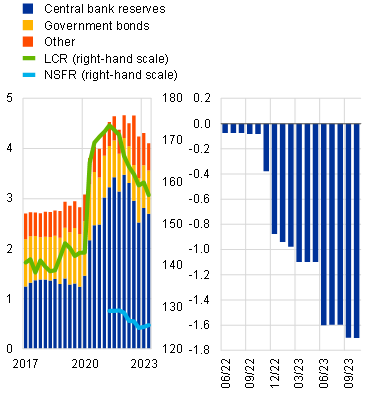

In addition, lower lending volumes and higher bank funding costs may weigh on euro area bank earnings going forward. Lending dynamics have slowed markedly as a result of tighter lending standards and weak credit demand, with year-to-date lending flows to households and firms reaching their lowest levels since 2015. Uncertain macro-financial conditions may continue to weigh on volume growth going forward, partly offsetting the positive margin effect of higher interest rates on banks’ net interest income. After the stress in the US and Swiss banking markets in the spring of this year, bank bond spreads stabilised at levels above historical averages. At the same time, the gradual shift from overnight to term deposits continued, with some signs of increased deposit competition among banks, but the pace of deposit repricing remains limited compared with previous hiking cycles. Looking ahead, bank funding costs are set to rise further as maturing liabilities reprice at higher levels (Chart 6, panel c), targeted longer-term refinancing operation (TLTRO) funds are gradually repaid and the composition of funding moves back towards long-run averages with a higher share of term deposits and bonds (Chapter 3). In terms of the management of interest rate risk, euro area banks have made increasing use of the interest rate swaps market since 2021, especially for longer maturities (Special Feature A).

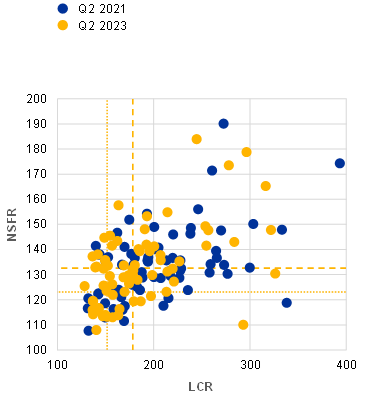

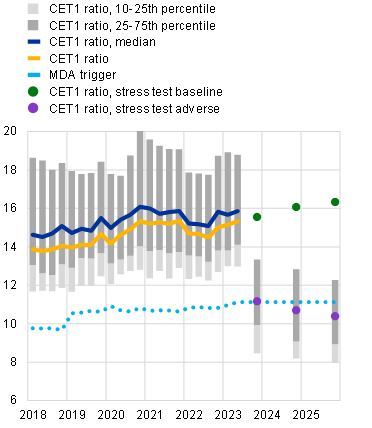

The resilience of the euro area banking sector is, in aggregate, underpinned by strong capital and liquidity positions. Euro area banks proved resilient to the bouts of stress in the US and Swiss banking markets earlier this year, building on solid bank fundamentals. Standard regulatory metrics point towards strong liquidity resilience overall, despite a recent decline in banks’ liquidity coverage ratios following TLTRO repayments. At the same time, with payout ratios increasing only slightly, capital ratios have risen in line with higher retained earnings. The euro area banking sector’s resilience to adverse shocks was also confirmed by the results of the European Banking Authority’s 2023 EU-wide stress test. To preserve resilience from a more structural perspective, euro area banks need to carefully manage the implications of climate change and should also address the risks posed by the digitalisation of the financial industry. Such risks include the accelerated pace of bank runs (Box 3), the growing threat from cyber risks and the challenges associated with the introduction of digital currencies (Box 4).

Chart 6

Rising rates helped bank profitability improve, but the prospect of deteriorating asset quality and higher funding costs increases downside risks to bank earnings

a) Euro area banks’ return on equity, cost of equity and price-to-book ratios | b) Default rates on banks’ corporate and retail exposures | c) New and existing rates on bank deposits and bonds |

|---|---|---|

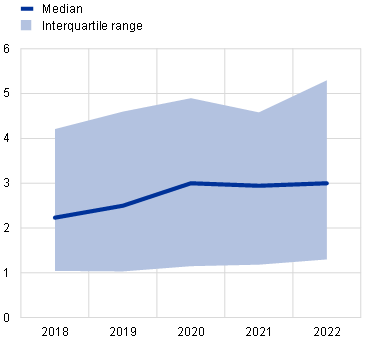

(Q1 2015-Q2 2023, percentages, ratios) | (Q1 2018-Q2 2023, percentages) | (Sep. 2023, percentages) |

|  |  |

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Dealogic, ECB (supervisory data, MIR) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: the dashed horizontal lines represent the long-term averages, i.e. Q4 2000-Q2 2023, for banks’ return on equity, cost of equity and price-to-book ratio. Banks’ estimated cost of equity is calculated following the methodology set out by Altavilla et al.* Panel b: annualised quarterly default rates (two-quarter moving averages). Panel c: for all funding sources except bonds, existing rates indicate the average annual rate paid over the last 12 months and the latest monthly observation so as to account for the timing of the recognition of higher expenses in profit and loss. For bonds, “New rates” refers to the weighted average yield at issuance on new issuances within the latest month and “Existing rates” to the weighted average yield at issuance for all outstanding bonds. MFIs/OFIs stands for monetary financial institutions/other financial institutions.

*) Altavilla, C., Bochmann, P., De Ryck, J., Dumitru, A., Grodzicki, M., Kick, H., Melo Fernandes, C., Mosthaf, J., O’Donnell, C. and Palligkinis, S., “Measuring the cost of equity of euro area banks”, Occasional Paper Series, No 254, ECB, 2021.

Despite greatly improved profitability and continued resilience across the sector, bank valuations have remained compressed. Among other things, this may be explained by the lingering structural problems across the industry (such as low cost-efficiency) and the high risk premia embedded in banks’ cost of equity (Box 5). Low valuations may also reflect concerns about the sustainability of bank profits, given one-off factors such as the imposition of bank levies – or discussions in that direction – in a number of countries, as well as the headwinds associated with the prospect of worsening asset quality and higher funding costs going forward.

Macroprudential policies should help safeguard and strengthen resilience across the financial system

Safeguarding banking sector resilience remains key to navigating the turn of the financial cycle. Euro area macroprudential authorities have increased capital buffer requirements further in recent months, thereby bolstering banks’ resilience. These actions have also strengthened the macroprudential policy space by expanding potentially releasable capital buffers. Macroprudential authorities should preserve these buffers to ensure that they remain available in case conditions in the banking sector deteriorate. They should also ensure that borrower-based measures remain in place as structural backstops to prevent lending standards deteriorating and to protect borrower quality. Beyond highlighting the importance of resilient banking systems, the lessons learnt from the stress in the US and Swiss banking markets in the spring of this year reaffirm the need to implement outstanding Basel III reforms and complete the banking union. Against this backdrop, recent initiatives to impose taxes on banks may have negative repercussions for financial stability, as they make it harder for banks to accumulate capital.

Structural vulnerabilities in different parts of the non-bank financial sector require a comprehensive policy response to increase resilience. Parts of the non-bank financial sector remain sensitive to adverse developments in macro-financial conditions that could place downward pressure on asset valuations, particularly in the case of riskier assets. Structural vulnerabilities arising from liquidity mismatches and leverage could amplify market-wide price corrections and aggravate liquidity stresses in the financial system. The large market footprint and interconnectedness of non-bank financial institutions make it all the more important to increase the sector’s resilience by developing a comprehensive set of policy measures across non-bank entities and activities, taking a macroprudential perspective. This includes enhancing the liquidity preparedness of non-bank market participants to meet margin and collateral calls, tackling risks from non-bank leverage and mitigating liquidity mismatch in open-ended funds. International policy coordination will be key in this context to promote a level playing field and minimise the risk of cross-border arbitrage.

1 Macro-financial and credit environment

1.1 A recession remains a possible scenario as an already weak economic outlook deteriorates

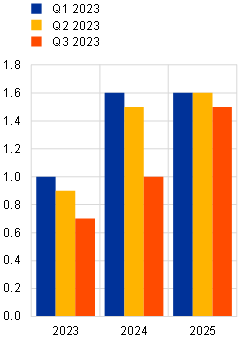

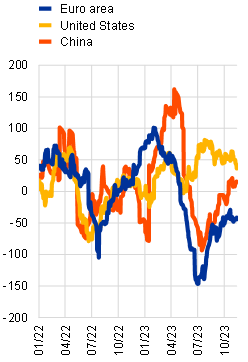

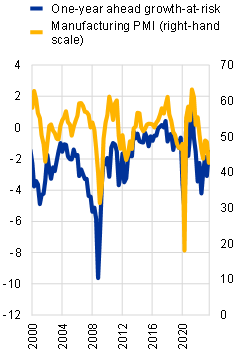

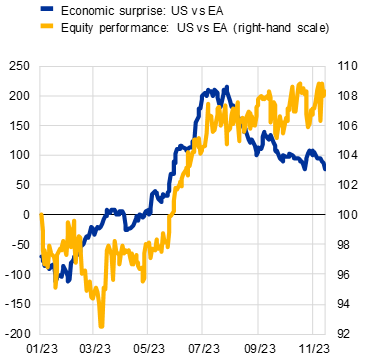

Several downward revisions to forecasts and negative economic surprises confirm a weak economic outlook with substantial downside risks. The ECB/Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections as well as other official and private sector forecasts were revised downwards for several quarters in a row, reflecting a worsened global economic environment, tighter financial conditions, lower aggregate demand and lower credit supply. Weak foreign demand and receding fiscal support are weighing on activity, too. As of the third quarter of 2023, GDP growth is expected to come in at 0.7% in 2023 and 1.0% in 2024, the latter being a reduction of 60 basis points compared with six months earlier (Chart 1.1, panel a). While economic surprises have been to the upside in the United States in 2023, the news has been predominantly more negative than expected for the euro area and China (Chart 1.1, panel b). Even though forecasts indicate that the euro area economy might enjoy a soft landing, a recession also remains a likely scenario (see also Chapter 2). This risk is captured by the manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) – historically a reliable predictor of GDP growth – being in clearly contractionary territory (below 50 index points) as of the third quarter of 2023 (Chart 1.1, panel c). In addition, the one-year ahead GDP growth-at-risk estimate indicates that, with a probability of 5%, economic growth within the next 12 months may turn out lower than -1.6%, which would mean a more severe contraction. This suggests that there are downward risks to overall economic activity in the euro area, albeit varying from country to country.

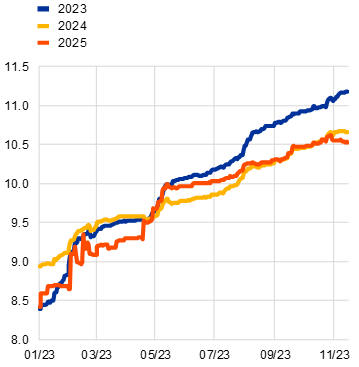

Chart 1.1

Several rounds of downward revisions to forecasts confirm a weak economic outlook

a) ECB forecasts for annual euro area GDP growth | b) Citi Economic Surprise Index | c) GDP growth-at-risk and euro area manufacturing PMI |

|---|---|---|

(2023-25, percentages) | (3 Jan. 2022-14 Nov. 2023, index) | (Q1 2000-Q3 2023, left-hand scale: percentages, right-hand scale: index) |

|  |  |

Sources: ECB/Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Citigroup, S&P Global Market Intelligence, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: includes GDP growth for Q1 and Q2 2023 as already reported at the time of publication. The respective forecasts are for the entirety of 2023 as per the respective ECB/Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projection rounds of Q1 through Q3 2023. Panel b: Citi Economic Surprise Index values above zero represent positive economic surprises in sum, while values below zero represent negative economic surprises. Panel c: growth-at-risk is the 5th percentile prediction of a quantile regression model estimated on a panel of euro area countries. Explanatory variables include GDP growth and indicators of cyclical systemic risk, financial stress, the debt service ratio and economic sentiment. See Lang, J.H., Rusnák, M. and Greiwe, M., “Medium-term growth-at-risk in the euro area”, Working Paper Series, No 2808, ECB, 2023.

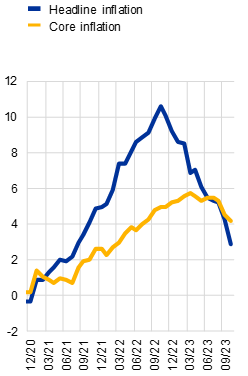

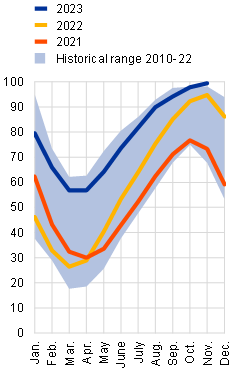

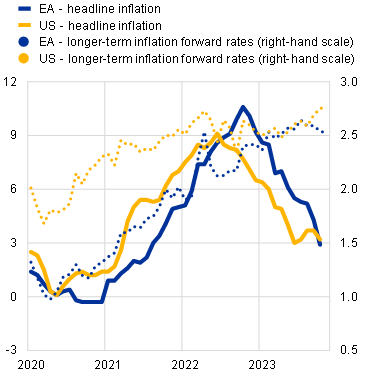

The risk of higher energy prices interrupting the ongoing decline of headline inflation cannot be ruled out. Headline inflation in the euro area declined notably from over 10% year on year in October 2022 to 2.9% in October 2023. The dispersion of inflation across countries also narrowed markedly. However, core inflation remains persistently high and only started to decline in September 2023 (Chart 1.2, panel a). The majority of professional forecasters see annual headline inflation declining to below 3.4% in 2024 and below 2.4% in 2025 (Chart 1.2, panel b).[1] Whether rising energy prices, especially for liquified natural gas, will affect inflation over the winter will largely depend on weather conditions, as well as on global economic and political developments. An interruption of liquified natural gas supplies from Russia or higher than expected demand from China could result in substantially higher prices, as energy price volatility remains elevated (Chapter 2). That said, the EU is entering the colder season well prepared, with natural gas storage facilities almost full (Chart 1.2, panel c). A continuation of the recent rise in oil prices or more notable increases due to a possible further escalation of the conflict in the Middle East may add to inflationary pressures as well as to downside risks to economic growth (Overview).

Chart 1.2

The decline in inflation could be challenged by rising energy prices in the event of a harsh winter or shifts in global economic and geopolitical risks

a) Euro area inflation | b) Headline inflation forecasts | c) EU natural gas storage levels |

|---|---|---|

(Dec. 2020-Oct. 2023, percentages) | (2023-25 as at Q3 2023, distribution, percentages) | (2010-23, total share, percentages) |

|  |  |

Sources: ECB, ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters and Bloomberg Finance L.P.

Notes: Panel a: the latest inflation data refer to October 2023. Panel b: the forecast distribution is as at Q3 2023. Panel c: the latest natural gas storage data are as at 14 November 2023.

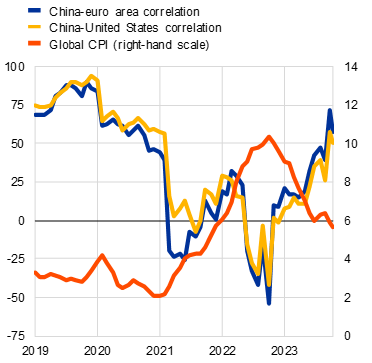

Euro area growth prospects may be adversely affected by a further slowdown of the Chinese economy and geopolitical tensions. The ongoing crisis in the Chinese real estate sector is weighing on economic activity in China, resulting in lower demand for European export goods, with a negative knock-on effect on euro area growth. Even though direct euro area bank exposures to the Chinese real estate sector are limited, other transmission channels may allow for spillovers, should the situation deteriorate further (Chapter 2). Generally, there might be a further aggravation of geopolitical risk from the conflict in the Middle East, the presidential elections in the United States in 2024, Russia’s continuing unjustified war against Ukraine and ongoing tensions between the United States and China. On the back of a weak economy and stubbornly high core inflation, turbulence in financial markets due to geopolitical tensions could easily exacerbate downward risks for economic growth and financial stability in the euro area. Currently, a further escalation of the conflict in the Middle East could induce instability through higher energy prices, with serious implications for inflation and potentially for monetary policy. Additionally, an escalation may also depress consumer sentiment and investor risk appetite, adversely impacting growth prospects in the euro area.

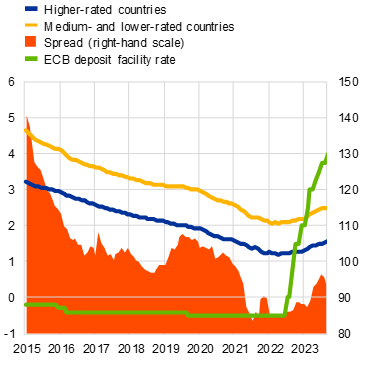

1.2 Sovereign vulnerabilities remain elevated due to higher refinancing costs and a weak macro-financial outlook

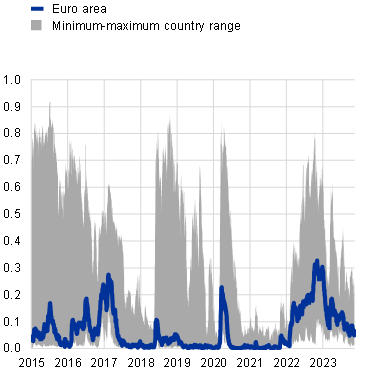

Stress in sovereign bond markets has generally receded, but risks remain elevated. Since the publication of the previous Financial Stability Review in May 2023, stress levels in sovereign bond markets have declined. Nevertheless, the dispersion across countries started to rise again at the end of September (Chart 1.3, panel a). As there are considerable differences across euro area countries and downside risks to fiscal positions, stress could increase again, especially if market participants perceive budget planning in some countries to be detrimental to longer-term debt sustainability. Overall, the euro area budget deficit is projected to decline over the coming years, accompanied by a tightening of the fiscal stance.[2] Such a tightening would help to ensure that fiscal policies are better aligned with the monetary policy response to inflation. While the expected phasing-out of government support measures introduced in response to the energy price shock and high inflation could help to achieve a tightening of the fiscal stance, governments might counteract this effect by introducing new stimulus measures in response to a stronger deterioration in economic activity, for example, or a renewed increase in energy prices. In addition, there are risks of delays in the implementation of the Next Generation EU programme, which may weigh on national sovereign budgets going forward, while heightened geopolitical tensions could require increases in defence spending.

The ongoing negotiations on reforming EU fiscal rules are inducing significant uncertainty. As the general escape clause contained in the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact will be deactivated by the end of 2023, reaching agreement is critical in order to anchor expectations for debt sustainability and sustainable, inclusive growth. Failure to swiftly agree on and put in place a credible, transparent and predictable fiscal framework could create uncertainty and unduly delay necessary fiscal adjustment and the impetus for reforms and investment.[3] Such uncertainty would likely lead to further increases in government bond yields and spreads (Chart 1.3, panel b), especially for countries that may then fail to comply with the Stability and Growth Pact and face excessive deficit procedures.

Chart 1.3

Stress in sovereign bond markets has receded, but uncertainty remains high

a) Euro area sovereign composite indicator of systemic stress | b) Ten-year government bond yields by rating group |

|---|---|

(1 Jan. 2015-14 Nov. 2023, index) | (1 Jan. 2020-14 Nov. 2023; left-hand scale: percentages, right-hand scale: basis points) |

|  |

Sources: ECB, Bloomberg Finance L.P., LSEG, S&P Global Market Intelligence, Moody’s Analytics, Fitch Ratings and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: the sovereign composite indicator of systemic stress is unit-free and lies within the interval (0, 1). The indicator is available for 11 euro area countries: Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal and Finland. See Garcia-de-Andoain, C. and Kremer, M., “Beyond spreads: measuring sovereign market stress in the euro area’’, Economics Letters, Vol. 159, 2017, pp. 153-156. Panel b: government bond yields are weighted by annual GDP as at 2022. Ratings refer to the average from Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch and represents the ratings as at 14 November 2023.

The euro area sovereign debt-to-GDP ratio declined further but is expected to remain above pre-pandemic levels over the medium term. The euro area government debt-to-GDP ratio has benefited from a favourable interest rate-growth differential (the snowball effect) over recent quarters and is expected to fall to 89% in 2023, significantly below the peak seen during the pandemic. In the light of upward pressure from primary deficits and positive deficit-debt adjustments, as well as a narrowing of the snowball effect, the ratio is projected to stabilise at around 88% over the course of 2024 and 2025, above the pre-pandemic level of 84%.[4] While the situation differs across euro area countries, debt levels generally remain elevated.

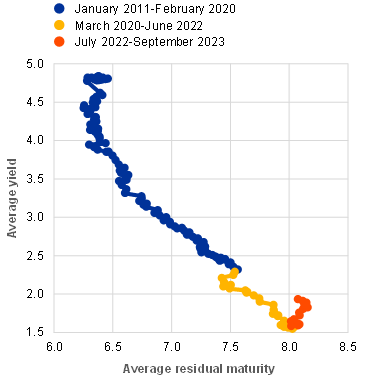

Sovereign debt service is still benefiting from the favourable financing conditions of the past but might face greater challenges in the future. Net debt issuance by euro area governments has been stable throughout 2023 – in line with previous years. With the Eurosystem reducing its footprint in sovereign bond markets, private sector actors like banks, non-bank financial institutions and foreign investors have stepped in to absorb fiscal issuance (Box 1). However, sentiment among such investors could change if fiscal policies in some euro area countries were perceived as detrimental to longer-term debt sustainability. During the pandemic, governments used favourable financing conditions to extend the maturity profile of their outstanding debt, helping to reduce refinancing risks going forward. While the currently higher interest rates feed slowly through to sovereign debt stocks, governments have broadly maintained the same maturity profile (Chart 1.4, panel a). At the same time, yields in sovereign bond markets are around 1.5 percentage points above the average yield on debt portfolios, indicating significant potential for increases in the interest burden as maturing debt is rolled over (Chart 1.4, panel b). Countries with higher short-term refinancing needs are likely to see a faster increase in their interest burden, which may pose challenges going forward.

Chart 1.4

Sovereigns have extended their debt maturity, but higher interest rates will increase their interest burden going forward

a) Average yield and residual maturity on the outstanding debt of euro area governments | b) Spread between current and average yields on outstanding government bonds and gross debt service due in one year |

|---|---|

(Jan. 2011-Sep. 2023; years, percentages) | (Q2 2023, Sep. 2023; percentages of GDP, percentage points) |

|  |

Sources: ECB (GFS), LSEG, Bloomberg Finance L.P. and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel b: the y-axis shows the difference between ten-year government bond yields and the average yield of the outstanding debt portfolio as at September 2023. Data for debt service due in one year refer to September 2023; data for the debt-to-GDP ratio refer to the second quarter of 2023.

Overall, risks to sovereign debt sustainability appear to be manageable in the short run, but medium-term challenges could add to financial stability risks. While debt levels in the euro area have stabilised, medium- and longer-term challenges such as geopolitical risks, climate change and ageing populations are adding to sovereign vulnerabilities. These challenges underline the need for a robust EU framework for economic and fiscal policy coordination and surveillance. The outlook for sovereigns may deteriorate if financial conditions tighten further, which would increase governments’ interest burdens, especially for sovereigns with high refinancing needs. In particular, debt sustainability concerns may arise going forward if governments do not pursue fiscally prudent paths or if highly indebted countries do not sufficiently reduce their debt ratios.

Box 1

Sovereign bond markets and financial stability: examining the risk to absorption capacity

The smooth absorption of sovereign debt issuance by the financial sector is essential for financial stability. Sovereign bonds are widely used as high-quality liquid assets and their prices serve as benchmarks for the pricing of various financial contracts. This means that the capacity of investors to absorb additional issuance is key for the orderly functioning of sovereign bond markets. Market conditions may have been impacted by reduced demand for government bonds as net purchases of sovereign debt by the Eurosystem came to a halt at the end of June 2022.[5] At the same time, the supply of government bonds is expected to remain high. Against this background, this box proposes a framework for assessing the potential challenges to financial stability related to the limits of the absorption capacities of different sectors active in sovereign bond markets.

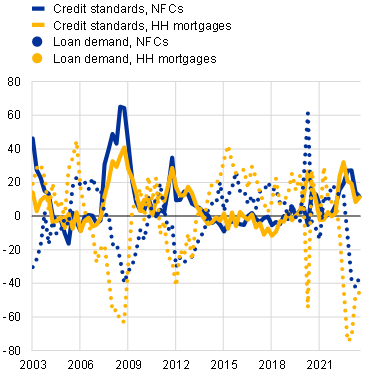

More1.3 Tight financial conditions are starting to weigh on the debt servicing capacity of non-financial corporations

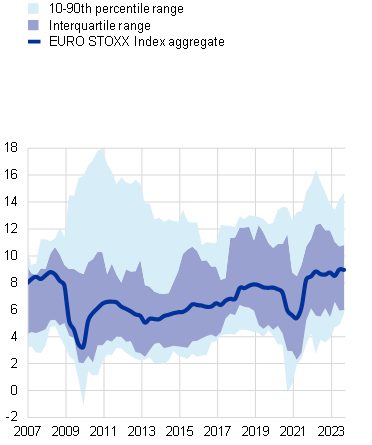

Euro area non-financial corporations (NFCs) entered the hiking cycle with resilient balance sheets, but activity is slowing in several sectors. A long period of ultra-low interest rates and a strong post-pandemic recovery helped the average corporate to build resilience. Euro area firms benefited from strong gross profits throughout the first half of 2023, reflecting continued rises in selling prices. This was also facilitated by firms maintaining their profit margins at stable levels (Chart 1.5, panel a). Growth has come to a halt across most sectors as the effects of the recovery have faded and the impact of tighter financial conditions has increased. So far, service-oriented sectors have not been as badly affected, but some industrial sectors are already contracting (Chart 1.5, panel b). Uncertainty around the future path of this slowdown persists. Downside risks could materialise, especially if inflation remains too high for too long and triggers a further tightening of financial conditions or if an external shock hits. This might take the form of renewed substantial rises in energy prices or supply bottlenecks, possibly driven by geopolitical tensions.

Chart 1.5

Firms maintain profit margins, but growth is slowing

a) Profit margins across EURO STOXX sectors | b) Growth in gross value added |

|---|---|

(Q1 2007-Q3 2023, percentages) | (Q1 2022-Q2 2023, percentages) |

|  |

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: the ranges in the chart cover the 17 non-financial sectors of the 20 sector indices that comprise the EURO STOXX Index. Panel b: growth in gross value added is shown as quarter-on-quarter changes in calendar-adjusted and seasonally adjusted gross value added.

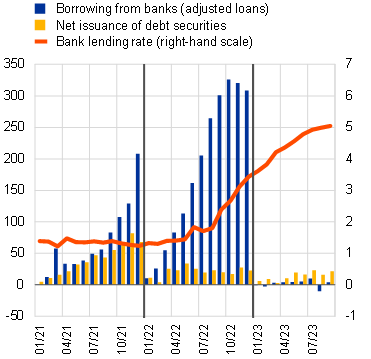

Firms have limited their borrowing in a climate of rising financing costs, causing leverage to decline. The increases in corporates’ financing costs over the past few months reflect the smooth transmission of monetary policy. The resulting tightening of credit standards by banks has been compounded by a drop in firms’ demand for external financing and has led to a material decline in lending volumes. Since the beginning of 2023, net borrowing from banks and net issuance of debt securities has almost come to a halt (Chart 1.6, panel a). The lower demand for credit also mirrors the greater availability of internal sources to fund capital expenditures, such as ample cash buffers and solid retained earnings built up during the post-pandemic recovery. The decline in new borrowing has also allowed the corporate sector to further deleverage, reducing gross debt[6] to 131% of gross value added in the second quarter of 2023, down by 10 percentage points year on year and below pre-pandemic levels.

Chart 1.6

Demand for bank loans stalls in a climate of rising interest rates and weakening debt service capacity

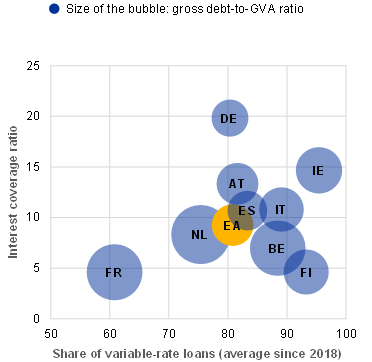

a) Borrowing costs, yearly cumulative net flows of bank borrowing and debt security issuance of euro area NFCs | b) Share of variable-rate lending and interest coverage ratios |

|---|---|

(Jan. 2021-Sep. 2023; € billions, percentages) | (Q2 2023; percentages, ratio) |

|  |

Sources: ECB (CSEC, BSI, MIR), Eurostat and ECB (QSA) and ECB calculations.

Note: Panel a: flows of bank loans are adjusted for loan sales and securitisation (resulting in derecognition from the MFI statistical balance sheet) as well as for positions arising from notional cash pooling services provided by monetary financial institutions. Net issuance of debt securities refers to the difference in gross issues and redemptions of debt securities by euro area NFCs at face value. Panel b: the x-axis shows the average of monthly shares of variable-rate loans and loans with an interest rate fixation period of up to one year in total new lending between January 2018 and September 2023. The interest coverage ratio is calculated as the four-quarter moving sum of the gross operating surplus of NFCs divided by the four-quarter moving sum of interest before the financial intermediation services indirectly measured (FISIM) allocation payable by NFCs. Gross debt is unconsolidated and comprises the sum of loans granted to NFCs, debt securities issued by NFCs and insurance, pension and standardised guarantee schemes of NFCs minus loans granted by NFCs. GVA stands for gross value added.

The debt servicing capacity of some firms may become a concern as higher interest rates feed through to corporate debt stocks. Prior to and during the pandemic, firms benefited from low interest rates, which helped to push interest coverage ratios up and default risks down. Because corporates generally have a larger share of adjustable-rate loans, they are affected by interest rate changes more quickly than other economic sectors. While the aggregate interest coverage ratio of euro area firms remained solid at 9.3 in the second quarter of 2023, higher interest expenses have already pushed it down by 2.7 percentage points compared with a year before. Interest expenses are expected to increase further with successive repricing of the loan stock. This may raise concerns over corporates’ debt servicing capacity, especially where debt levels are high and interest coverage ratios are low (Chart 1.6, panel b).

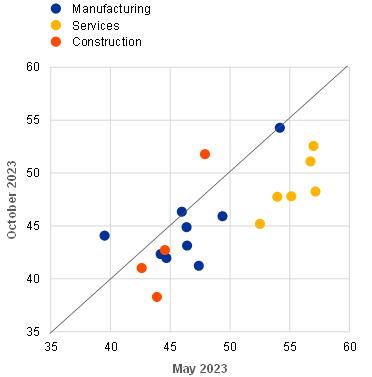

Although generally still low, bankruptcies have started picking up, with some euro area countries seeing pre-pandemic levels surpassed. The more challenging macro-financial conditions, together with vulnerabilities built up over the pandemic, have led to an increase in insolvencies across countries (Chart 1.7, panel a). While this partly reflects the reduction of the insolvency backlog that accumulated during the pandemic, defaults are likely to rise further, with high-frequency indicators suggesting that the economic downturn is becoming more broad-based across countries and sectors (Chart 1.7, panel b). Default risk could particularly affect firms that have not recovered from the strains inflicted by the pandemic and last year’s energy price shock and could increase should energy prices take off again.

Chart 1.7

Bankruptcies are increasing as the outlook for economic growth deteriorates

a) Corporate bankruptcies | b) PMIs across sectors and countries |

|---|---|

(Q4 2019-Q2 2023; index: Q4 2019 = 100) | (index) |

|  |

Sources: Eurostat, INE, S&P Global Market Intelligence and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: the bankruptcy index provided by Eurostat for Spain shows a sizeable pickup in Spanish bankruptcies, driven largely by sole proprietors, the removal of the bankruptcy moratorium in June 2022 and the amended Spanish Bankruptcy Law which entered into force on 26 September 2022. To ensure comparability with the indices for other countries, the chart shows Spanish bankruptcies obtained from INE that exclude natural persons. The euro area aggregate is calculated using the INE data for Spain. Panel b: points show euro area countries for which sectoral PMIs are available. For the manufacturing PMI, these comprise the euro area aggregate, Germany, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Austria; for the services PMI, they comprise the euro area aggregate, Germany, Ireland, Spain, France and Italy; and for the construction PMI, they comprise the euro area aggregate, Germany, France and Italy. Dots below the 45-degree line signal a deterioration between the two points in time. Values below 50 signal a contraction of output, values above 50 an expansion.

Overall, corporate vulnerabilities have increased as financial conditions have tightened and the economic outlook has weakened. There is considerable diversity across firms, despite them being resilient on average, as higher financing costs and a weakening macroeconomic outlook are now adding to the challenges they have faced over the past few years. The interest burden for corporates will likely increase further as debt has to be refinanced at higher rates once sources of internal funding have been depleted. In addition, some debt instruments, such as leveraged loans, are more sensitive to rate increases and might be particularly exposed should financial conditions tighten further. This means that the number of vulnerable firms that have difficulty servicing their debt is likely to increase. Accordingly, there could be more defaults going forward, with potential knock-on effects on bank balance sheets, non-bank investors in corporate debt (Chapter 4) and household employment prospects.

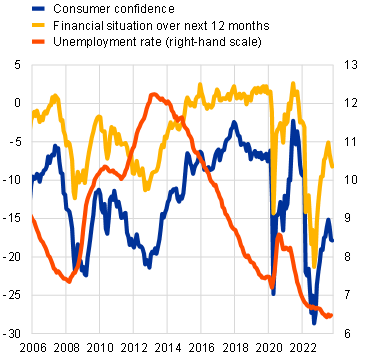

1.4 Households benefit from a strong labour market but face higher debt service costs

Euro area households continue to benefit from record levels of employment and, more recently, rising wages. Consumer confidence and households’ self-reported financial situations had been improving since the publication of the previous issue of the Financial Stability Review on the back of a very robust labour market and declining headline inflation. However, this improvement came to a halt in July 2023 before going into reverse and remaining markedly below pre-pandemic levels (Chart 1.8, panel a). After real compensation per employee suffered a substantial fall in 2022, negotiated wages have picked up significantly recently. While no concrete signs of the labour market turning have emerged as yet, the rate of change in the unemployment rate has flattened out in recent months and the number of people unemployed has slowly started to rise in some countries. The sound financial position of households overall is mirrored by the household vulnerability indicator, which stands below its long-run average (Chart 1.8, panel b).

Chart 1.8

Households benefit from a strong labour market, but prospects are subdued as initial signs of higher debt service costs emerge and the unemployment rate bottoms out

a) Consumer confidence, households’ expectations about their financial situation, and unemployment rate | b) Composite indicator of household vulnerabilities |

|---|---|

(Jan. 2006-Oct. 2023, left-hand scale: indices, right-hand scale: percentages) | (Q1 2000-Q2 2023, standard deviations from long-run average) |

|  |

Sources: European Commission, Eurostat, ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panel a: the latest observation for the unemployment rate is for September 2023. Panel b: the composite indicator is based on a broad set of indicators along five dimensions: debt servicing capacity (measured by gross interest payments-to-income ratio, savings ratio and expectation of personal financial situation); leverage (gross debt-to-income and gross debt-to-total assets ratios); financing (bank lending rate, short-term debt-to-long-term debt ratio, quick ratio (defined as current financial assets/current liabilities) and credit impulse (defined as the change in new credit issued as a share of GDP)); income (real income growth and income-to-GDP ratio); and activity (labour participation rate and unemployment expectations). The indicators are standardised by transforming them into z-scores, i.e. they are converted into a common scale with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Composite sub-indicators are calculated for each of the five dimensions by taking the simple arithmetic mean of the respective underlying z-scores of the individual indicators. Finally, the overall composite indicator is obtained by equally weighting the composite z-scores of the five sub-categories. Positive values indicate higher vulnerability, negative values lower vulnerability.

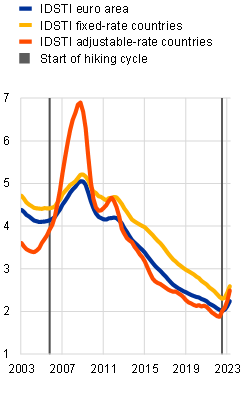

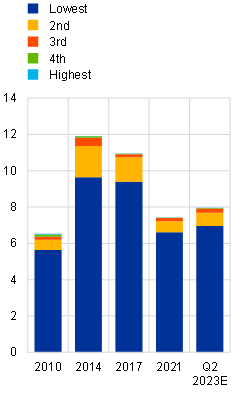

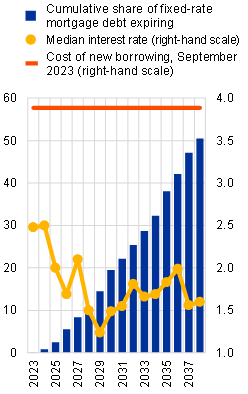

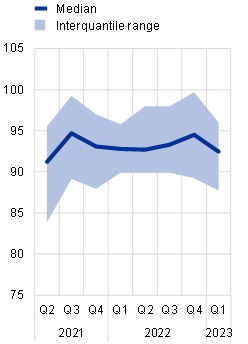

Household vulnerabilities are rising slowly due to deteriorating debt servicing capacity as higher policy rates feed through. The sharp decline in loan demand triggered by rising policy rates since 2022 has led to a drop in household leverage, reducing overall vulnerabilities. Similarly, the household vulnerability indicator’s activity component reflecting the strong labour market is contributing to declining vulnerabilities. The income component is reverting to neutral territory, as real wages are catching up. However, the recent deterioration in households’ debt servicing capacity is adding to aggregate vulnerabilities. The significant increase in the cost of borrowing in the euro area has recently started to have an impact on mortgage debt service costs. Variable-rate mortgages and fixed-rate mortgages at the end of their rate fixation period are being repriced at interest rates that are much higher than they were a year ago or at origination. Worse debt servicing capacities are also reflected in the recent increase in the interest debt service-to-income (IDSTI) ratio for the euro area (Chart 1.9, panel a), in particular for countries where variable-rate mortgages predominate, while for most traditionally fixed-rate countries the ratio remained largely unchanged (Special Feature B).

Chart 1.9

Euro area household sector buttressed by sufficient cash flows and savings, but increase in debt service cost will weigh on households’ financial situations

a) Interest debt service-to-income (IDSTI) ratio | b) Share of illiquid households, by income quintile | c) Wall of fixed-rate mortgage debt expiration |

|---|---|---|

(Q1 2003-Q2 2023, percentages) | (2010-Q2 2023, percentages) | (2023-38, percentages) |

|  |  |

Sources: ECB (nowcasted Household Finance and Consumption Survey) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Panels b and c: the nowcasting methodology brings the most recent survey data from 2021 forward to Q2 2023 by micro-simulating the development of individual households’ incomes, savings, expenditures and debt holdings according to aggregate macro-financial data. Structural shifts in aggregate employment and mortgage origination patterns are taken into account. A household is defined as illiquid when its income cash flow is negative after all expenses and its savings do not cover more than one month of total debt service.

Households remain solvent despite first signs of higher debt service costs on variable-rate loans, while fixed-rate loans could pose a problem down the line. Micro-simulations using household survey data nowcasted to the first quarter of 2023 reveal that the share of households with a debt service-to-gross-income ratio of above 30%, which indicates elevated risk of default, increased from 12% to 14% between the first quarter of 2022 and the second quarter of 2023. In some countries with a share of variable-rate mortgages that is very high by historical standards, the increase has been even greater. At present, however, the micro-simulations do not show signs of a substantial increase in the share of illiquid households, as free cash flows – supported by the tight labour market – and savings buffers – supported by legacy excess savings from the pandemic – have not yet become impaired (Chart 1.9, panel b). During the period of ultra-low interest rates, households originated and refinanced large volumes of mortgages at very favourable conditions. That said, estimates based on nowcasted survey data show that over 30% of the euro area’s outstanding fixed-rate mortgage stock is expected to expire within the next ten years (Chart 1.9, panel c). These mortgages have median interest rates of between 1.5% and 2.0%, and debt service payments would have to be recalculated at market rates when the interest rate fixation expires. Depending on the future average cost of borrowing at the time, this repricing could result in a significant surge in debt service costs in countries where fixed-rate mortgages predominate. Since inflated house prices have driven up mortgage volumes substantially in several countries, even more affluent households may become financially stretched by increasing total debt service costs.[7]

Household debt service costs are expected to increase further, with associated risks for euro area financial stability; however, the most vulnerable households hold little debt. Lower-income households, which are benefiting in particular from strong labour markets, constitute by far the largest share of illiquid households. However, their debt share has been very stable over time and makes up only around 10% of euro area mortgage debt and 20% of consumer debt, effectively limiting banks’ exposure. Going forward, higher debt service costs from variable-rate loans (over the short to medium term) and from fixed-rate mortgages (over the medium to long term) pose an increasing threat to households’ financial health and hence to the stability of the banking system in the euro area. Strong labour markets and sufficient savings are currently preventing higher debt service costs from leading to more defaults. That said, debt service costs are expected to increase further, and the September 2023 ECB staff macroeconomic projections already predict a slight increase in the unemployment rate to 6.7% in 2024. A significant deterioration of labour market conditions may put even middle-income households at risk, however.

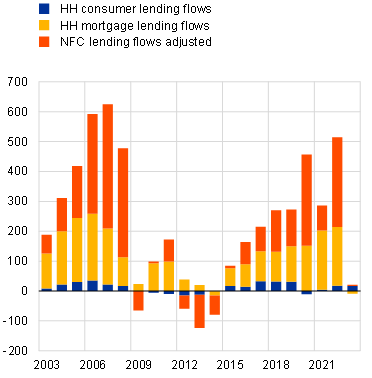

1.5 Euro area residential and commercial real estate markets are experiencing a downturn

Euro area residential real estate (RRE) prices exhibited a year-on-year decline in the second quarter of 2023. The steep increase in borrowing costs since the beginning of the tightening cycle has had a negative impact on the demand for mortgages, leading to a sharp drop in new lending. The general level of interest rates, the reduction in consumer confidence and deteriorating housing market prospects are the main drivers behind the dwindling demand for housing loans. In line with falling new lending, euro area RRE price growth declined from 9.2% in the second quarter of 2022 to -1.7% in the second quarter of 2023. Model-based evidence suggests that monetary policy tightening is the main factor putting downward pressure on house prices, followed by changes in household preferences and tighter bank credit standards (Special Feature B). Although euro area RRE price dynamics only recently turned negative, prices had already started declining in some euro area countries in the second half of 2022. High-frequency data suggest that the pace of the decline in RRE prices has slowed over recent months (Chart 1.10, panel a), indicating a price correction that has been orderly so far.[8] Euro area rental prices, on the other hand, are rising at a record pace – in September 2023 they were up 2.7% year on year.

Chart 1.10

RRE prices are declining at a slower pace, but valuations still seem stretched in several countries, suggesting that further price falls are likely

a) High-frequency RRE prices in selected countries | b) Overvaluation estimates across euro area countries |

|---|---|

(Dec. 2019-Aug. 2023; index: December 2019 = 100) | (Q4 2019, Q2 2022, Q2 2023; percentages) |

|  |

Sources: ECB, Europace, Eurostat, Immobiliare.it, Meilleursagents.com, Confidencial Imobiliário, Arco Real Estate, Národná banka Slovenska, Statistics Finland, Irish Central Statistics Office and Statistics Netherlands.

Notes: Panel a: the chart includes monthly data up to August 2023 for the following countries: Germany, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Portugal and the Netherlands. For Slovakia, data are quarterly and up to June 2023. An average listing price index is used for Italy, while a hedonic price index based on transaction prices is used for all the other countries. Panel b: the chart shows deviations from the long-term average of the house price-to-income ratio, which constitute an indication of potential overvaluation in domestic housing markets. The long-term average is calculated from Q1 1996 to the respective end quarter. The average of two measures (inverted demand econometric model and house price-to-income ratio) was employed in previous editions of the Financial Stability Review, but the inverted demand model might underestimate overvaluation in a period of high inflation due to its use of real interest rates. Accordingly, the house price-to-income ratio is being employed as the benchmark overvaluation measure in the current edition of the Financial Stability Review.

RRE valuations are still above pre-pandemic levels in several euro area countries, suggesting that vulnerabilities remain elevated. RRE prices grew at a fast pace during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, rising significantly quicker than household incomes, which, in turn, pushed up estimated valuations of housing prices. These remain significantly above pre-pandemic levels, despite the fall in RRE prices witnessed thus far in some euro area countries (Chart 1.10, panel b).[9] Higher interest rates are likely to result in further downward pressure on house prices as they weigh on demand for new loans, while the debt servicing capacity of households with outstanding mortgages could deteriorate (Section 1.4). This is especially the case in countries where valuations are stretched, debt levels are elevated, or household mortgage debt is largely composed of variable-rate loans. Indeed, banks still expect the demand for housing loans to decline in the fourth quarter of 2023, but at a slower pace than in the previous five quarters. Together with supply-side shortages and high construction prices, this might contain the fall in RRE prices in the near term.

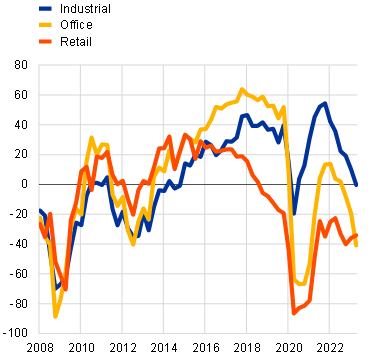

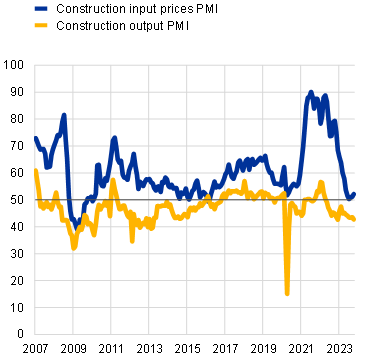

The outlook for commercial real estate (CRE) firms has continued to deteriorate in a context of falling tenant demand and negative credit rating actions. Transaction activity in CRE markets remains subdued (-47% in the first half of 2023 compared with the first half of 2022), although this may change in the coming quarters as the future path of interest rates becomes clearer. Any increase in market activity will aid price discovery but may result in significant declines in transaction prices as the market prices in a year of monetary policy tightening. The effects of this tightening are amplified by falling demand for CRE assets in the wake of the pandemic, with demand for office space dropping significantly over the course of 2023 (Chart 1.11, panel a). This dual challenge has driven significant credit rating activity for real estate firms over recent months. For example, S&P has downgraded 22% of European real estate firms since 2022 and a further 26% are on negative outlook. Looking at the combined actions of all credit rating agencies, market analysts estimate that €6 billion of bonds issued by European real estate firms were downgraded to high yield between May and August this year and that a further €10 billion in bonds remain vulnerable. Conditions are particularly challenging for property developers, who face falling sales prices, contracting order books and rising input costs, although price pressure from input materials has reduced in recent months (Chart 1.11, panel b). These factors resulted in a number of smaller German developers filing for bankruptcy in September. Construction sector PMIs have deteriorated in recent months, although they remain far above the lows seen during the pandemic and the global financial crisis (Chart 1.11, panel b).

Chart 1.11

The outlook for CRE markets continues to deteriorate, with landlords facing falling demand and developers under additional pressure from input costs

a) Change in number of tenancy enquiries in three months | b) PMI for construction sector input prices and output |

|---|---|

(Q1 2008-Q2 2023, percentages) | (Jan. 2007-Oct. 2023, index) |

|  |

Sources: RICS, ECB calculations and S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Notes: Panel b: a value above 50 denotes an increase and a value below 50 denotes a decrease (in confidence or prices). PMI stands for Purchasing Managers’ Index.

The implications of the ongoing real estate correction for financial stability critically depend on the extent to which tighter financial and credit conditions reduce real estate demand and affordability. The downward adjustment in RRE prices has so far taken place in an orderly manner. However, risks remain tilted to the downside, especially in those countries where debt levels are elevated and properties might be overvalued. The commercial segment has seen a steeper downturn, and the combination of rising financing costs and falling rental incomes could pose repayment capacity challenges. Despite negative credit rating actions, so far there is limited evidence of credit supply restrictions, fire sales or a widespread deterioration in credit quality among CRE firms. Banks’ aggregate exposures are substantially smaller for CRE than for RRE and are unlikely to be large enough at the euro area level to cause a systemic crisis alone. Nevertheless, a scenario where real estate firms suffer very large losses is likely to coincide with stress in other sectors. In this way, CRE market outcomes have the potential to act as a significant amplifying factor in an adverse scenario, increasing the likelihood of systemically relevant losses accruing in the banking system (Special Feature B). While macroprudential policy should focus on maintaining the resilience of the banking sector at the current juncture, current levels of banking sector profitability may provide an opportunity for further targeted increases of macroprudential buffers in some countries while avoiding procyclical effects (Chapter 5).

2 Financial markets

2.1 Markets adjust to an environment of higher rates

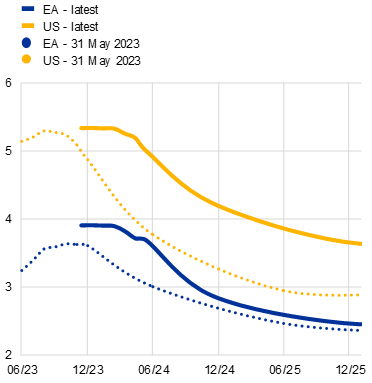

Market participants’ view that there is a heightened risk of persistent inflation has led them to revise their expectations for interest rates to remain elevated for a longer period of time. Falling inflation (Chart 2.1, panel a) has encouraged major central banks to moderate the pace of policy rate hikes. In addition, the prospect of nearing the end of the rate-hiking cycle lowered the implied volatility in risk-free interest rate markets and supported investor sentiment until August. At the same time, however, longer-term inflation swap forward rates have stayed elevated (Chart 2.1, panel a), as resilient labour markets, the energy transition, climate change and heightened geopolitical tensions may contribute to greater inflation persistence and economic uncertainty.[10] Consequently, market participants have also adjusted their expectations regarding the future path of short-term interest rates and have priced them as remaining at elevated levels for an extended period of time (Chart 2.1, panel b). Over September and October a rapid increase in long-term government bond yields in line with this trend, as well as on the back of rising term premia, put renewed pressure on asset valuations. However, the market correction proved to be short-lived, as investor confidence benefited from a downside surprise in inflation.

Chart 2.1

Investor expectations of inflation persistence have led them to price in higher-for-longer rates

a) Headline inflation and longer-term inflation swap forward rates | b) Market-implied short-term interest rate expectations |

|---|---|

(Jan. 2020-Nov. 2023, annual percentage changes) | (percentages) |

|  |

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P. and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for 14 November 2023. Panel a: longer-term inflation swap forward rates refer to 5Y5Y swaps on HICP (euro area) and CPI (United States). Panel b: risk-neutral market expectations for one-month rates based on the €STR OIS and the USD SOFR OIS forward curves.

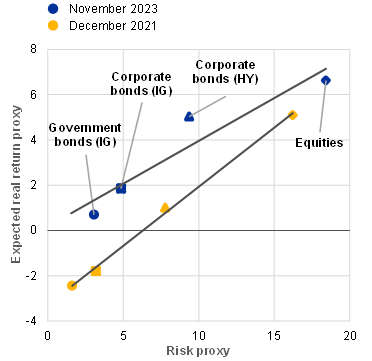

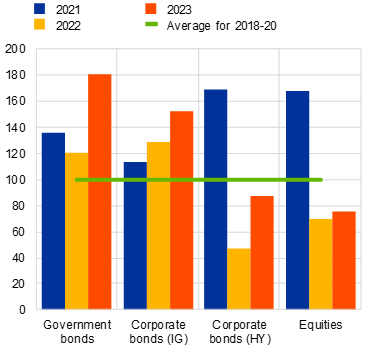

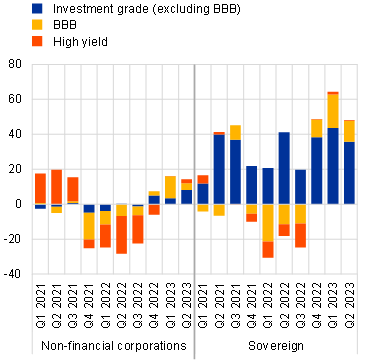

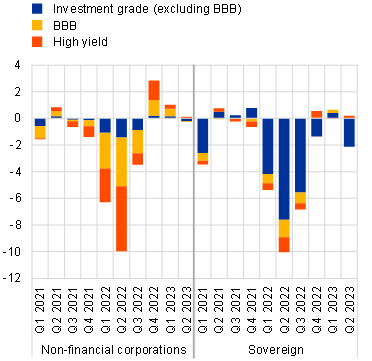

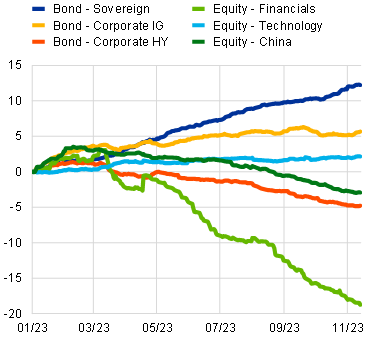

A period of higher interest rates may bring long-term benefits for the stability of the financial system, but it could also temporarily increase market volatility. The era of ultra-low interest rates was associated with an accumulation of financial stability risks.[11] In financial markets, these risks were linked primarily to search-for-yield behaviour, resulting in increased leverage and exposure to risky assets and causing a build-up of market and credit risks that in some cases may have exceeded risk-bearing capacities.[12] As a result, the transition to a higher interest rate environment has triggered a reversal which is visible in de-risking trends as safer assets have become increasingly appealing to investors (Chart 2.2, panel a). Net flows into investment funds exposed to riskier asset classes have also been substantially lower (Chapter 4). The crowding out of riskier assets has so far mostly been evident in primary market volumes, with the gross issuance of euro area high-yield bonds and equities declining considerably during the normalisation of monetary policy (Chart 2.2, panel b). In the secondary market, the rise in real risk-free rates has induced a correction in equity prices, albeit of limited extent to date. Such resilience may be attributed partly to reduced supply from new issuance, on top of the robust demand stemming from the soft-landing expectations or from investors who see equities as a better inflation hedge than fixed income securities. Going forward, compressed risk premia leave global equity markets vulnerable to disorderly repricing if risk sentiment deteriorates. Such correction could be exacerbated by heightened leverage in the equity options market (Box 2).

Chart 2.2

The transition to a higher interest rate environment has reduced the issuance of riskier assets

a) Real return and risk metrics for euro-denominated asset classes | b) Changes in gross issuance of securities by euro area entities |

|---|---|

(percentages) | (Jan.-Nov., 2018-23; average for 2018-20 = 100) |

|  |

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P. and ECB calculations.

Notes: The latest observations are for 14 November 2023. IG stands for investment grade; HY stands for high yield. Panel a: calculated on the basis of Bloomberg euro-denominated total return bond indices for three- to five-year maturities and on the EURO STOXX Index. Expected real returns are proxied by the weighted average yield to maturity adjusted by inflation swap rates on the euro area HICP matching index average maturity (for debt indices) and by the five-year cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) yield (for the equity index). Risk is proxied by the rolling five-year annualised volatility of monthly returns. Fitted lines are linear functions. Panel b: rating groups are based on the average rating assigned to a given issuer.

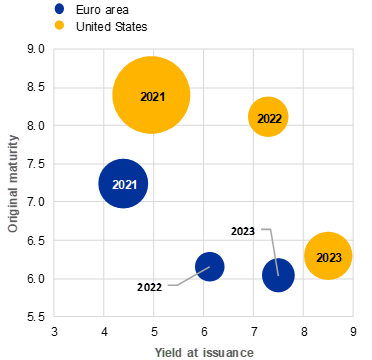

The impact of policy tightening on riskier borrowers may be greater in the medium term. Lower-rated corporate borrowers issued a record amount of debt shortly before the onset of the tightening cycle (Chart 2.2, panel b). This may have enabled them to reduce issuance in 2022 and 2023 to some degree, which shielded them from the immediate effects of higher risk-free rates and wider spreads on their funding costs. Some firms which still opted for market-based funding have issued new bonds but with shorter maturities, potentially aiming to lower the risk premia demanded by investors or hoping that monetary policy would ease faster than currently anticipated (Chart 2.3, panel a). These two trends have recently caused the average maturity of outstanding high-yield debt to fall to historical lows (Chart 2.3, panel b). While such debt management strategies could prove beneficial for borrowers if tight monetary policy is short-lived, they might increase rollover risks, especially in a higher-for-longer environment. In particular, shorter debt maturities leave lower-rated firms more exposed to future market conditions. If a delay in the impact of policy tightening on funding costs coincides with an already slowing economy, this could lead to a further rapid decline in interest coverage ratios (Chapter 1) and cause a disorderly price correction in the high-yield bond market.

Chart 2.3

High-yield issuers are increasingly exposed to refinancing risk

a) High-yield bond issuance characteristics | b) Average remaining maturity on outstanding high-yield bonds |

|---|---|

(2021-23 year to date; percentages, years) | (Jan. 2015-Nov. 2023, years) |

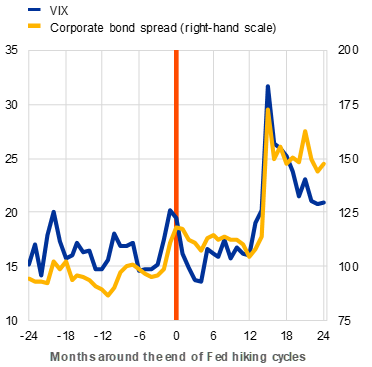

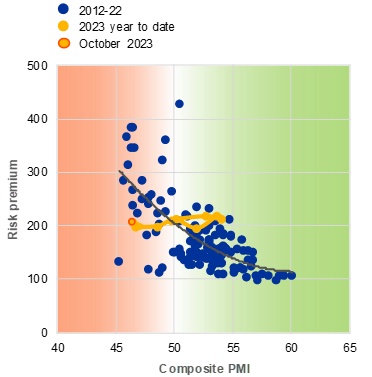

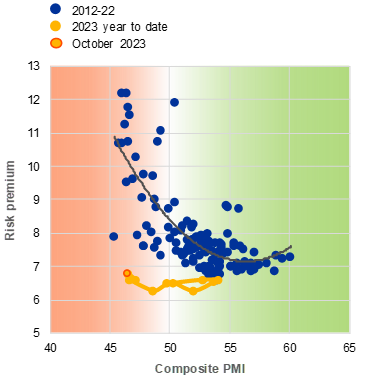

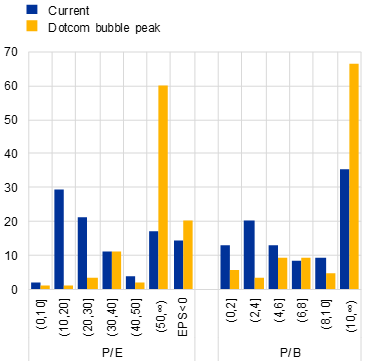

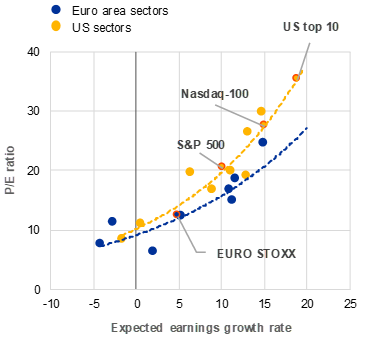

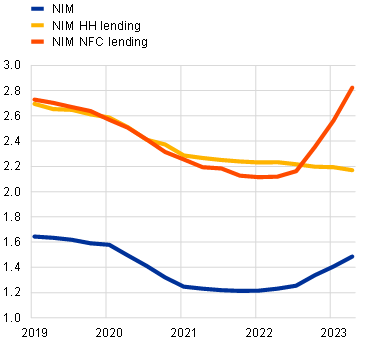

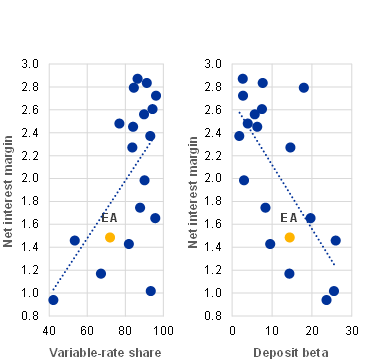

|  |