Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5/2023.

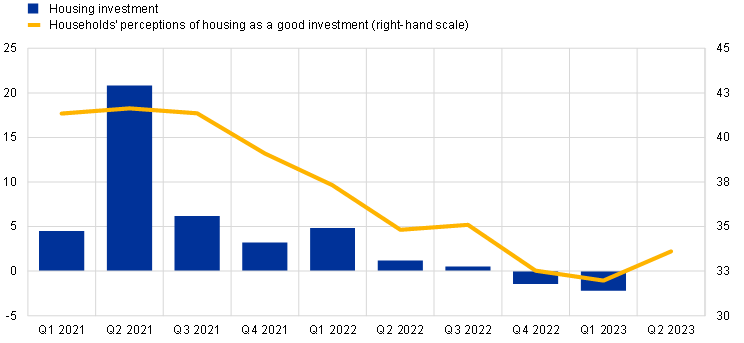

The deterioration in household perceptions of housing as a good investment preceded the recent decline in housing investment in the euro area.[1] In the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey (CES), households are regularly asked whether they think buying a property in their neighbourhood today is a good or bad investment.[2] The proportion of positive responses to this question then may be used as a proxy of housing demand, which is an important driver of housing investment.[3] Indeed, household perceptions of housing as a good investment were a relatively good leading indicator of the weakness in housing investment that began in the second quarter of 2022, with household perceptions falling from their peak in the second quarter of 2021 to a low point in the first quarter of 2023 (Chart A). Since the turn of the year, these perceptions have recovered somewhat but remain at a low level. This box analyses the factors determining household perceptions of the attractiveness of housing as an investment using CES data on household characteristics and expectations, thereby shedding light on the reasons for the recent slowdown in housing investment.

Chart A

Housing investment and households’ perceptions of housing as an investment

(left-hand scale: year-on-year percentage changes; right-hand scale: percentages of respondents)

Sources: Eurostat, CES and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Households’ perceptions of housing as an investment measures the share of respondents who consider buying a property in their neighbourhood today to be a “good” or “very good” investment. Quarterly averages of monthly data. The value for Q2 2023 corresponds to the average of monthly data for April and May 2023.

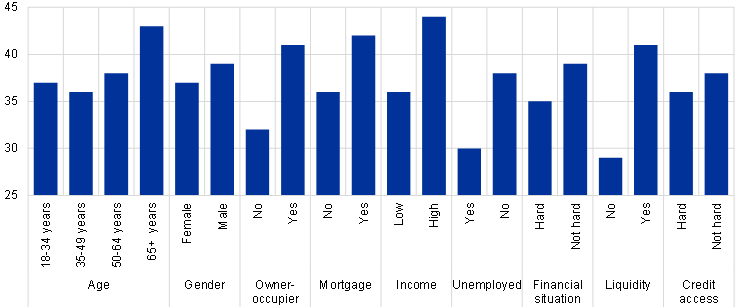

Households perceive housing as an investment differently depending on their demographic and economic characteristics. Looking at the different characteristics of households surveyed in the CES, there are striking variations in the perceptions of the attractiveness of housing as an investment across specific groups (Chart B). On average, older consumers and males report a greater willingness to invest in housing than younger consumers and females. Owner-occupiers (particularly those with a mortgage) and those who claim to be more financially literate are also more likely to consider housing as a good investment than households that do not own a home, do not have a mortgage or do not consider themselves very financially literate.[4] While these characteristics could affect household perceptions of housing investment per se, differences in economic characteristics across household segments could also play an important role. Data on household income, working status, availability of sufficient liquidity, perceived financial situation and the tightness of credit access show that financially stronger households are typically more likely to believe that housing is a good investment.[5] This suggests that these households are either more able or more willing to risk such a large illiquid investment as housing.[6]

Chart B

Household perceptions of housing as a good investment according to their demographic and economic characteristics

(percentages of respondents)

Sources: CES and ECB staff calculations.

Note: The chart shows average values for households’ perceptions of housing as a good investment per household segment as a share of respondents who consider buying a property in their neighbourhood today to be a “good” or “very good” investment between April 2020 and May 2023.

Household expectations are an important factor in explaining household perceptions of housing as a good investment.[7] In addition to the different characteristics of households, their expectations also play an important role in their tendency to consider housing as a good investment. This is due to the fact that housing investment is associated with a long-term horizon for spending and borrowing decisions, so households need to form a view on future economic developments.

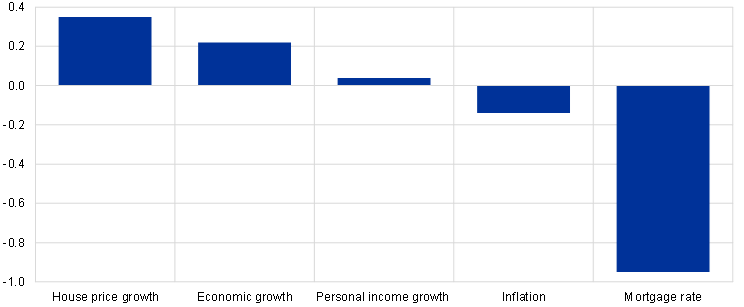

To formally assess the relationship between household perceptions of housing as a good investment and their expectations, we use a linear probability regression model that controls for the multiple factors at play. The model accounts for various expectations affecting the attractiveness of housing as an investment. These include household expectations of personal income growth, inflation, economic growth, house price growth and mortgage rates for the next 12 months, while controlling for household characteristics such as household income, working status, financial situation, liquidity availability, access to credit, and individual, wave and/or country-fixed effects.[8]

The model shows that higher expectations for economic growth, personal income growth and house price growth are associated with higher perceptions of housing as a good investment (Chart C). By contrast, higher inflation and mortgage rate expectations are associated with lower perceptions of housing as a good investment. This might be explained by the negative real income effects of higher inflation and the cash-flow effects of higher debt servicing costs, both of which weigh on housing demand.[9] As for the control variables, liquidity availability and financial situation are statistically significant; ample liquidity has a positive association with households’ perceptions of housing as an investment, while a difficult financial situation has a negative association.

Chart C

Estimated regression coefficients

(percentage points)

Sources: CES and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The chart shows the estimated coefficients for household expectations derived from a linear probability regression model in which a household’s individual perception of housing as a good investment is regressed on its expectations for personal income growth, inflation, economic growth, house prices and mortgage rates for the next 12 months. The model also controls for household income, working status, financial situation, liquidity, access to credit, and individual, wave and/or country-fixed effects. A coefficient of 1 means that, for a 1 percentage point increase in households’ expectations, the probability that respondents will consider housing a good investment increases by 1 percentage point. All estimated coefficients are statistically different from zero at the 1% level. The sample is for the period from April 2020 to May 2023.

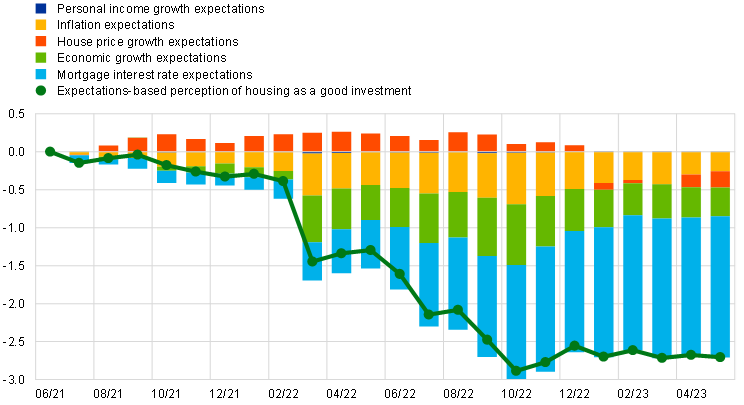

Household expectations of higher mortgage rates, higher inflation and lower economic growth have weighed heavily on their perceptions of housing as a good investment since mid-2021 (Chart D). Using the estimated model parameters for household expectations of personal income growth, inflation, economic growth, house price growth and mortgage interest rates, as well as the average expectations of households surveyed in the CES at each point in time, we can derive an expectations-based indicator of household perceptions of housing as a good investment.[10] This indicator fell sharply in 2022, but it has stabilised since late 2022, broadly in line with the actual share of households that consider housing a good investment. The decline in this expectations-based indicator was mainly due to rising mortgage interest rate expectations, which were exacerbated by rising short-term inflation expectations in early 2022, lower economic growth expectations, and falling house price growth expectations in late 2022. The dampening effect of mortgage interest rate expectations intensified in early 2023, together with deteriorating expectations for house price growth, while inflation expectations declined and thus had less of a restraining effect.[11] Overall, the expectations for higher mortgage rates led households to assess housing as being a significantly less attractive investment, reflecting the impact of tighter monetary policy and financial conditions in general.[12]

Chart D

Expectations-based indicator of households’ perceptions of housing as an investment

(percentage point changes in the probability of households considering housing as a good investment since June 2021)

Sources: CES and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The chart reports the change since June 2021 in the expectations-based indicator of households’ perceptions of housing as a good investment. It combines the estimated coefficients of the linear probability regression model reported in Chart C with households’ average expectations for personal income growth, inflation, economic growth, house price growth and mortgage interest rates, as surveyed in the CES at each point in time.

For a discussion of the weakness of housing investment in the euro area in 2022 and a comparison with the United States, see the box entitled “Monetary policy and housing investment in the euro area and the United States”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3, ECB, 2023.

The study uses CES data from Belgium, Germany, Spain, France, Italy and the Netherlands.

The recovery in housing demand during the pandemic is discussed in the box entitled “The recovery of housing demand through the lens of the Consumer Expectations Survey”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB, 2021.

Financial literacy is measured in the CES using three basic questions to assess financial knowledge, together with a more knowledge-intensive mortgage borrowing question. For the precise wording, see, for instance, the appendix in Ehrmann, M., Georgarakos, D. and Kenny, G., “Credibility gains from communicating with the public: evidence from the ECB's new monetary policy strategy”, Working Paper Series, No 2785, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, February 2023.

In the CES, the question about sufficient liquidity asks households if they have sufficient financial resources to meet an unexpected payment equal to one month of household income. The question about credit access asks if it is easier or harder for the household to obtain credit or loans today compared with 12 months ago and is measured on a five-point scale ranging from much harder to much easier. The CES also asks respondents if their financial situation is much worse, somewhat worse, about the same, somewhat better or much better compared with 12 months ago.

The differences in mean scores for the age, gender, owner-occupier, mortgage, income, unemployment, financial situation, liquidity and credit access groups are statistically different from zero at the 1% significance level.

For a review of the recent literature on the determinants of survey-based housing market expectations, see Kuchler, T., Piazzesi, M. and Stroebel, J., “Housing market expectations”, NBER Working Paper, No 29909, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2022.

The choice of the specific variables for household expectations is motivated by macroeconomic studies that model housing demand, such as Kohlscheen, E., Mehrotra, A. and Mihaljek, D., “Residential Investment and Economic Activity: Evidence from the Past Five Decades”, International Journal of Central Banking, Vol. 16, No 6, December 2020.

Overall, these results broadly correspond to those reported in Qian (2023) for the United States. In particular, the results on inflation expectations are in line with the supply-side interpretation of inflation stressed in Candia et al. (2020) and support the findings in Bachmann et al. (2015) for the United States. However, the results contradict the conclusions of Duca et al. (2018) for the euro area, who find that a higher expected change in inflation is associated with a higher probability that households will make major purchases. Moreover, the results reported in this box also point to the minor role of housing as a hedge against inflation, contrary to the findings in Malmendier and Steiny Wellsjo (2023), who focus on long-run inflation experiences rather than near-term inflation expectations. See Qian, W., “House price expectations and household consumption”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 151, 104652, June 2023; Candia, B., Coibion, O. and Gorodnichenko, Y., “Communication and the Beliefs of Economic Agents”, NBER Working Paper, No 27800, National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2020; Bachmann, R., Berg, T.O. and Sims, E.R., “Inflation expectations and Readiness to Spend: Cross-sectional evidence”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 7, No 1: pp. 1-35; Duca, I.A., Kenny G. and Reuter, A., “Inflation expectations, consumption and the lower bound: micro evidence from a large euro area survey”, Working Paper Series, No 2196, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, November 2018; Malmendier, U., and Steiny Wellsjo, A., “Rent or Buy? Inflation Experiences and Homeownership within and across Countries”, Journal of Finance, forthcoming, 2023.

The expectations-based indicator measures changes in the likelihood that households will consider housing as a good investment, assuming there is no change in their demographic and economic characteristics. The expectations-based indicator explains about 80% of the volatility over time in households’ perceptions of housing as an investment, as shown in Chart A.

Despite their statistical significance, expectations for personal income growth do not appear to be quantitatively important drivers of the recent deterioration in the expectations-based indicator of housing as a good investment, as fluctuations in this variable since June 2021 have been relatively small.

For a discussion of housing as a component of the transmission of monetary policy to the economy, see the box entitled “The role of housing wealth in the transmission of monetary policy” in this issue of the Economic Bulletin.