- THE ECB BLOG

Which workers are most affected by changes in the policy rate?

19 October 2022

The ECB Blog investigates how change in the policy rate affects wages very differently depending on characteristics of employees and firms, such as firms’ size and their access to credit. Results show that the effects are symmetric during times of easing and tightening.

The ECB uses its policy rates to achieve price stability. But its decisions also have side effects on labour markets. To better understand how interest rate cuts and hikes affect labour market outcomes we look at workers, firms and credit. We investigate how characteristics such as workers’ age and education, or the size of the companies where they are employed, determine the extent to which payslips and hours worked are affected by monetary policy decisions.

But how can we gather the necessary information? We link two datasets from Portugal: one dataset provides detailed information on the employees of firms, and the other, information on loans to those firms.[1] Both date back to the launch of the euro. This allows us to match data on individual workers and the firms they work for, with the bank loans the firms drew down over two decades which includes periods of monetary policy easing and tightening.[2]

Our work began before the recent monetary policy normalisation and was initially focused on periods of monetary easing but we can prove that the effects are symmetric, for both policy easing and tightening. For example, workers with high education tend to benefit most after rate cuts in terms of wage increases and hours worked. But they are also among the most affected when the ECB increases policy interest rates, which slows wage growth. At the same time, workers in small and young firms are the most positively affected by policy rate cuts in terms of wage increases and hours worked. But they are also among the most affected during policy rate hikes.

But let us take a step back and look at the design of our study.

Rate cuts affect wages more in small firms

The recent public debate about the distributive effects of monetary policy has focused on workers’ income, age, race[3] and origin. There is also evidence that employers’ characteristics drive wage differences. To find out more we took three steps:

- We investigated which firms benefit the most from policy rate changes

- We then assessed which employees in these firms benefited the most

- We looked at the loan data to understand the role of credit in this context

Step 1: In which type of firms do workers benefit the most from ECB rate changes?

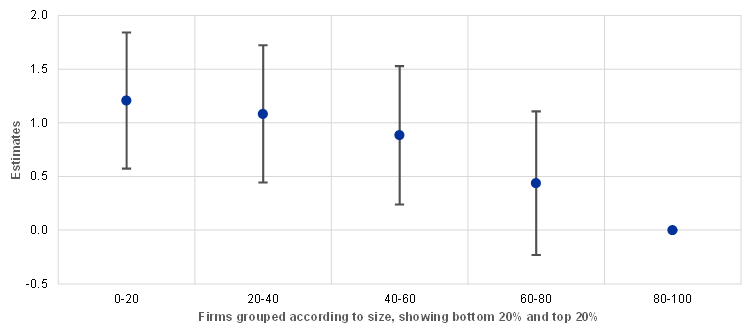

We address this question by estimating the heterogeneous impact of monetary policy conditions on wages, hours worked and employment across different types of firms. We estimate that a 1 percentage point (pp) decrease in the monetary policy rate is associated with a 1.16 pp stronger increase in wages of workers in small firms compared to large firms, as shown by Chart 1. Smaller firms increase wages more after a rate cut than bigger firms. We also estimate that workers in young firms benefit the most compared to workers in old firms. Since workers in smaller and younger firms tend to earn lower wages, policy rate cuts narrow the wage differential across firms in the economy.

Step 2: Which type of workers benefit the most from policy rate changes?

To address this question, we assess the impact of monetary policy on workers with high vs low levels of education. Following a monetary policy rate cut, the hours worked and wages earned by employees with more education increase by more than those of less educated workers. In particular, the labour market effects are most pronounced for better educated workers in small firms. Interest rate cuts are associated with the movement of highly educated workers towards small firms. In turn, this is coupled with a stronger increase in capital investment in small firms. What could be the reason for that? One interpretation is that small firms can often have less success securing credit than larger firms. This handicap is reduced in the aftermath of monetary policy easing. Small firms use improved access to finance for more capital investment, and this increases the value for better educated employees. So, we took a closer look at credit in our third step.

Chart 1

Monetary policy, wages and firm size

Estimated impact of one percentage point policy rate cut, on average wages, of firms of different sizes.

Dots represent the mean estimates of impact on wages. The vertical lines represent the variation in these estimates (‘’margin of error’’).

Sources: Jasova, Mendicino, Panetti, Peydro, Supera (2022). Notes: X-axis shows the size of firms. They increase in size relative to each other as you move right along the x-axis. The y-axis shows the estimated wage increase of employees in the firms represented on the x-axis. The wage increase estimated on the y-axis is always relative to the increases in wages in the largest firms (these firms are visible in the 80-100 quintile). In all cases, the impact on wages has been caused by a 1 percentage point cut in the monetary policy rate.

Monetary easing improves access to credit for small firms

Step 3: What is the role of credit in driving wage differentials after a rate cut?

We start by comparing the impact of a rate cut on wages for firms with and without bank credit. We find that credit plays an important role in explaining the effects of monetary rate changes on the distribution of wages. The wage outcomes for workers in small firms is fully driven by firms with an existing bank-borrowing relationship. In fact, for small firms without bank credit, it simply does not matter. Next, we use a novel measure of firm-level credit sensitivity to monetary policy, as well as measures of bank health, to capture financial constraints that firm and/or banks, respectively, might be experiencing. By alleviating financial constraints, monetary policy rate cuts allow easier access to credit for constrained firms and for firms borrowing from more constrained banks. Workers in these firms benefit more in terms of wages earned and hours worked when rates are falling. In particular, we also find that these effects depend on the state of the economy and are 2 to 3.5 times stronger in crisis periods than in normal times.

What is most relevant at present is that the effects of policy rate changes are symmetric for times of easing and tightening. So, in times of increasing policy rates, the wages of workers in larger firms are less negatively affected than those in smaller firms. This increases the wage differential across firms in the economy. But, at the same time, workers with less education are less affected. Since low-education workers tend to earn lower wages, rate increases narrow the wage differential across workers in the economy.

While the traditional view in macroeconomics focuses on aggregate effects, more recent research sheds a light on how heterogeneous the effects of monetary policy can be. It is important for policymakers to be aware that their decisions affect different types of workers and firms differently for at least two reasons. First, understanding the distributional consequences of monetary policy can help policymakers understand the impact of their actions on inequality. In this respect, earnings are a relevant source of inequality. Second, understanding heterogeneity can also be important to draw conclusions for aggregate effects, and especially so, in a monetary union where countries differ in their compositions of workers and firms. In this post we have argued that the repercussions of monetary policy on workers’ individual wages vary depending on whether they work in small or large firms as well as on their education level. Hence, the overall impact of policy rate changes in a country is going to be affected by the share of small vs large firms as well as by the share of workers with high vs low education levels.

Subscribe to the ECB blogThe views expressed in each article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

All results reported in this blog will be made available in Jasova, Mendicino, Panetti, Peydro, Supera, 2022 (Monetary Policy, Labour Income Redistribution and the Credit Channel: Evidence from Matched Employer-Employee and Credit Registers, forthcoming, ECB Working Paper)

Portuguese data are special in that they allow us to follow workers over time as they move across different firms and, at the same time, have a detailed picture of firm borrowing conditions. The results presented in this article are derived from two primary matched datasets. The first is the linked employee-employer dataset covering all private sector employees in Portugal (Quadros de Pessoal) constructed by the Portuguese Ministry of Labour Solidarity and Social Security. The second is the credit register reporting monthly level data on all loans that firms receive from credit institutions supervised by the Bank of Portugal (Central de Responsabilidades de Credito). In addition, the analysis uses firm-level balance sheet data (Informacao Empresarial Simplificada) and Bank of Portugal’s proprietary bank balance sheet data (Balanco das Instituicoes Monetarias e Financeiras).

See, among others, Dossche, Slacalek and Wolswijk, Monetary Policy and Inequality, Economic Bulletin Article, European Central Bank Economic Bulletin Issue 2, 2021, and references therein.