Preface

As part of its efforts to streamline and focus its publications, the ECB has decided to combine the previous report on “Financial integration in Europe” (last published in May 2018)[1] and the previous “Report on financial structures” (last published in October 2017)[2] into a single report on “Financial integration and structure” in the euro area. This report is designed to focus on structural developments in the financial system of the euro area, and in some cases also of the European Union (EU), and related policy issues. It will be published at a biennial frequency. The new report will, first, pay specific attention to key structural developments such as the process of financial integration, changes in financial structure and the process of financial development or modernisation. Second, it will discuss selected financial sector policies, notably policies related to the European banking union and capital markets union (CMU), and thereby also contribute to the debate on how European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) can be deepened.

For the ECB, the market for a given set of financial instruments and/or services is fully integrated if all potential market participants with the same relevant characteristics: (1) face a single set of rules when they decide to transact in those financial instruments and/or services; (2) have equal access to the above-mentioned set of financial instruments and/or services; and (3) are treated equally when they are active in the market.[3] The financial structure of a financial system can be understood as the mixture of financial intermediaries and of financial markets operating within the economy of that system.[4] One way of defining financial development (or financial modernisation for an already highly developed financial system like the one of the euro area) is the process of financial innovations, as well as institutional and organisational improvements in the financial system that reduces asymmetric information, increases the completeness of markets and contracting possibilities, reduces transaction costs and ensures a high level of competition.[5]

The Eurosystem has a keen interest in the integration, structure and development of the financial system in Europe, and especially in the euro area. All three interact with the implementation of monetary policy and influence its transmission throughout the euro area. All three also interact in multiple ways with financial stability. In addition, financial integration and development are two reasons behind the Eurosystem’s task of promoting well-functioning payment systems. Without prejudice to price stability, the Eurosystem also supports the objective of completing the EU Single Market, of which the banking union (since 2012) and the capital markets union (since 2014) have become important drivers in the financial services area. For all these reasons, the ECB monitors and assesses financial integration, structure and development and expresses its views on relevant policy options.

In general, each issue of the report will contain a first chapter reviewing the main trends in financial integration, structure and development, and a set of special feature articles and boxes, which will provide deeper analyses of specific issues or policies. This first issue of the new report includes special features and boxes on:

- the implications of Brexit for the EU/euro area financial system;

- the need to take the CMU project further;

- the implications of a common sovereign safe asset for the functioning of the banking and capital markets unions;

- euro area cross-border bank mergers and acquisitions in an international context;

- the role of equity markets in “greening” the economy; and

- the euro area fintech scene and how to improve the related statistics.

The ECB has since September 2005 released biannual updates of a set of indicators of financial integration. Similarly, since November 2004 it has also published a selection of EU structural financial indicators in the “Report on financial structures” (previously the “Report on EU banking structure”). Going forward, the ECB will continue these practices with a biannual release of a streamlined set of indicators covering both financial integration and financial structure.

Key messages

1 Overall assessment of financial structure and integration

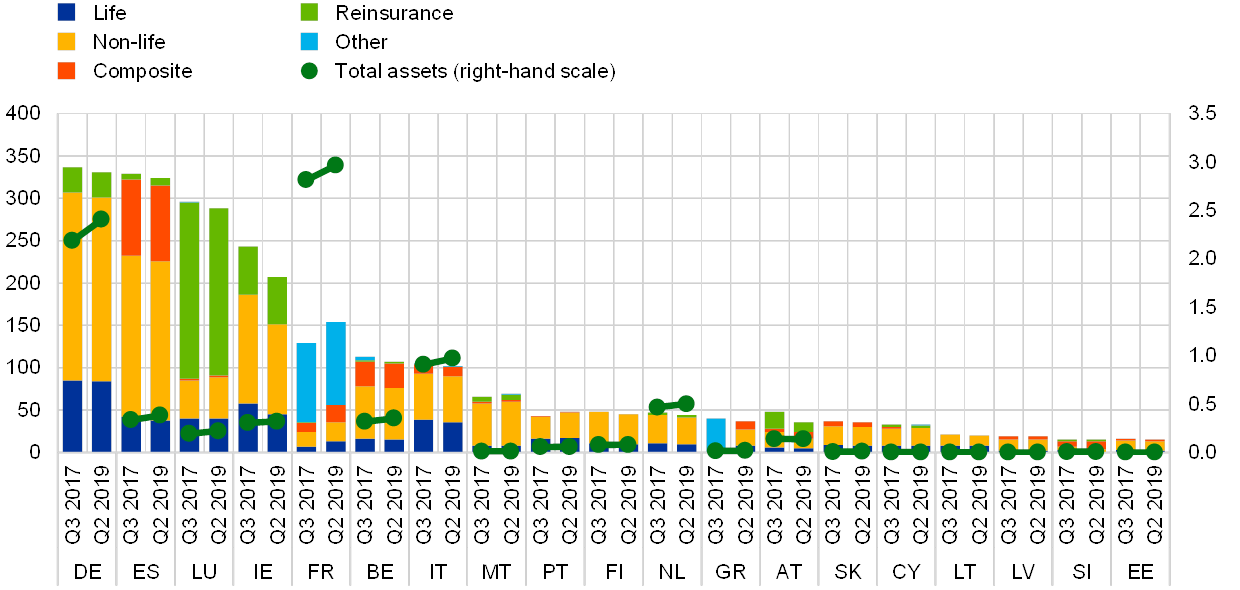

The size of the euro area financial system has been broadly stable in the last few years at a level around six to seven times GDP, roughly in line with the relative sizes of financial systems in other major countries. The overall size of a financial system can be estimated, among other ways, from the assets of financial intermediaries or from the liabilities of all economic sectors. In June 2019 the total stock of assets held by euro area financial intermediaries amounted to €82 trillion (including assets held by the Eurosystem). This is more than seven times euro area GDP (see Chart 1.1, left panel). This figure has changed little since 2015. At the end of 2018 total financing of euro area sectors stood at €67 trillion, which is almost six times euro area GDP and has changed little since about 2014. Such proxies of total financial system size also constitute one way of assessing the development of a financial system in an economy. They are indicative of the capacity that a financial system has to channel funds of agents with surpluses to agents in need of financing for consumption or productive investment purposes. At the same time, the financial crisis that started in 2007 illustrated that too large a financial system could indicate widespread imbalances and therefore pose a serious threat to financial stability and, ultimately, economic welfare. Moreover, there are other dimensions of financial development that may not be reflected well in total assets or liabilities, such as financial innovations, as well as institutional and organisational improvements in the financial system.

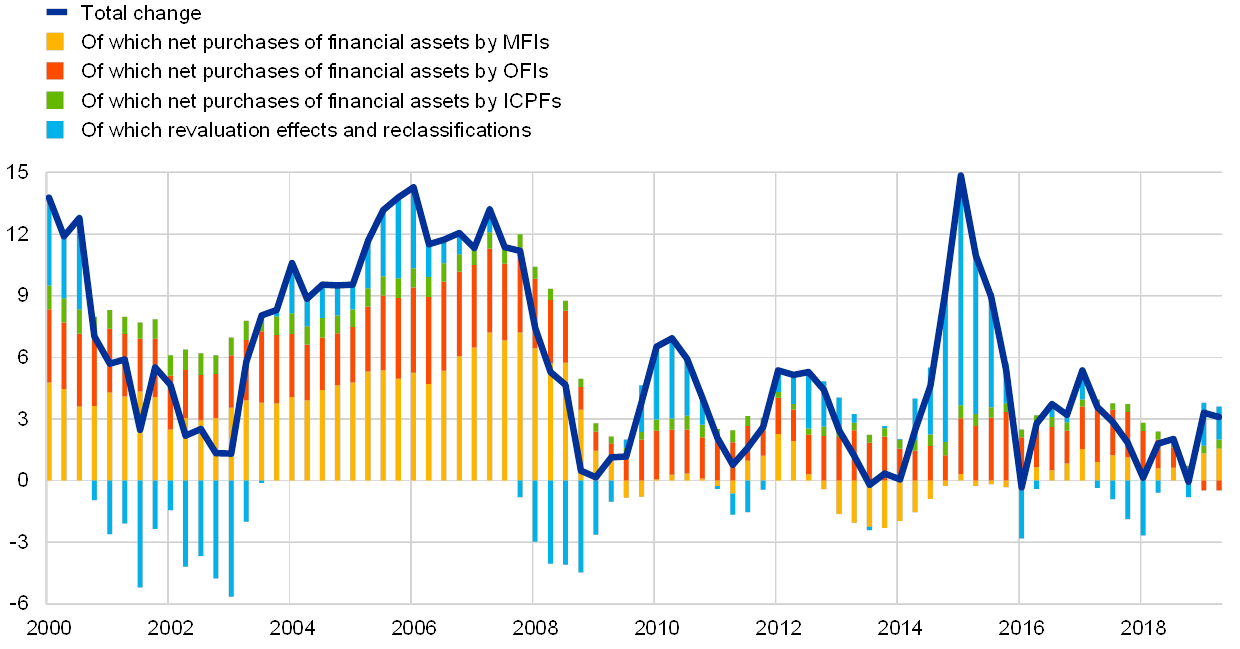

In terms of the roles of different financial intermediaries, the euro area financial structure shows a medium-term movement from strong bank dominance towards a more balanced composition, in which different types of non-bank financial intermediaries are becoming increasingly important. Another dimension that characterises a financial system is its structure, which refers to the mixture of financial intermediaries and financial markets that operate in the economy. For example, the right panel of Chart 1.1 shows that – by assets – the largest financial sub-sector remains banks (credit institutions), although their share has consistently declined since the early 2000s. At the same time, the importance of non-money market investment funds, of a residual category of “remaining” other financial institutions[6] (comprising a wide set of different intermediaries and other entities, including security and derivatives dealers or brokers, insurance brokers, asset management companies, venture capital companies, investment advisers, financial holding companies, specialised lending companies, funding vehicles of non-financial corporations – e.g. supporting their debt securities issuance – and other entities that channel financial flows within non-financial corporations), and of the Eurosystem increased. In other words, in terms of the asset shares of different types of financial intermediaries, bank dominance in the euro area financial system has weakened, notably after the financial and sovereign debt crises.

Chart 1.1

Total assets of the euro area financial sector and shares of different types of financial intermediaries

(ratio of assets to nominal GDP (left panel); percentages (right panel); March 1999 -June 2019)

Source: ECB.

Notes: The aggregated (non-consolidated) assets of sub-sectors include financial assets and exclude non-financial assets. Remaining other financial institutions include security and derivative dealers, financial corporations engaged in lending (such as leasing or factoring companies), specialised financial corporations (including venture capital companies, export/import financing companies or some central clearing counterparties), financial auxiliaries (including for example asset management companies, securities brokers, investment advisers, insurance brokers or exchanges) as well as captive financial institutions and money lenders (including for example financial holding companies, funding vehicles of non-financial corporations – e.g. supporting their debt securities issuance – and other entities that channel financial flows within non-financial corporations). Data on money market funds are reported separately from credit institutions only as of Q1 2006. Data on financial vehicle corporations, which are undertakings carrying out securitisation transactions, are reported separately from remaining other financial institutions as of Q4 2009.

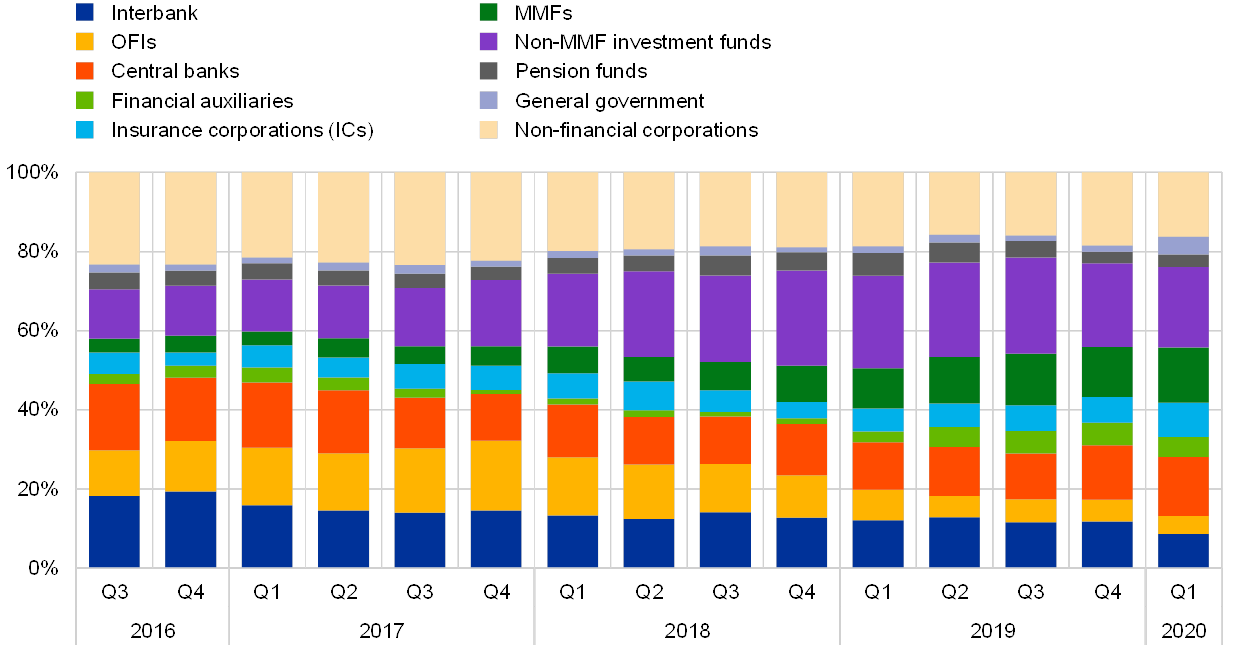

Investment and pension funds have been the fastest-growing types of non-bank financial intermediaries in the euro area over the last few years. Non-bank financial intermediaries (all areas in Chart 1.1, except the dark blue one for credit institutions and the yellow one for the Eurosystem), which accounted in June 2019 for almost 60% of total euro area financial sector assets, deserve particular attention. This is not only because their growth may represent financial development and a more diversified financial system, but also because it may reflect – in part – the migration of risks from the banking sector, which was re-regulated significantly after the crisis, to less regulated financial sub-sectors. A first observation in this regard is that the remaining other financial institutions (OFIs), which cannot be broken down with the currently available statistics and therefore remains relatively opaque, constitutes a substantial share of non-bank financial intermediaries by assets. A second observation is that investment funds and pension funds have been the fastest-growing categories in recent years and investment funds had already earlier become the second largest non-bank financial intermediary group in the euro area behind the residual remaining OFIs. The third and fourth largest types of non-bank intermediaries are insurance corporations and pension funds, respectively.

While non-bank financial intermediary growth has a number of benefits reflecting financial development, it also calls for prudential policy attention to how to contain transforming and potential newly emerging or even increasing financial stability risks. Investment fund growth is important for a variety of reasons. First, European households still hold a relatively large share of their savings in bank deposits, but in the current low interest rate environment various types of investment funds (based on past experience) offer more attractive returns on well-diversified portfolios. Second, many types of investment funds offer cross-country diversification for equities, bonds or other (less tradable) assets, which makes them natural conduits for private financial risk sharing in the euro area. The recent adoption of an EU directive and regulation to promote the cross-border distribution of investment funds may be helpful in this regard.[7] Third, the growing financial flows into investment funds, combined with increasing liquidity mismatches on their balance sheets (see, for example, sub-section 4.2 of the November 2019 ECB Financial Stability Review), may lead to greater financial stability risks and therefore require prudential policy attention. The recommendations published by the Financial Stability Board in 2017 and the European Systemic Risk Board in 2018 aim to address structural vulnerabilities of asset managers arising, in particular, from liquidity mismatches.[8] Progress in implementing these recommendations in Europe can be achieved in the context of a review of EU legislation, such as the ongoing review of the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive, for which a public consultation is expected in the second half of 2020.

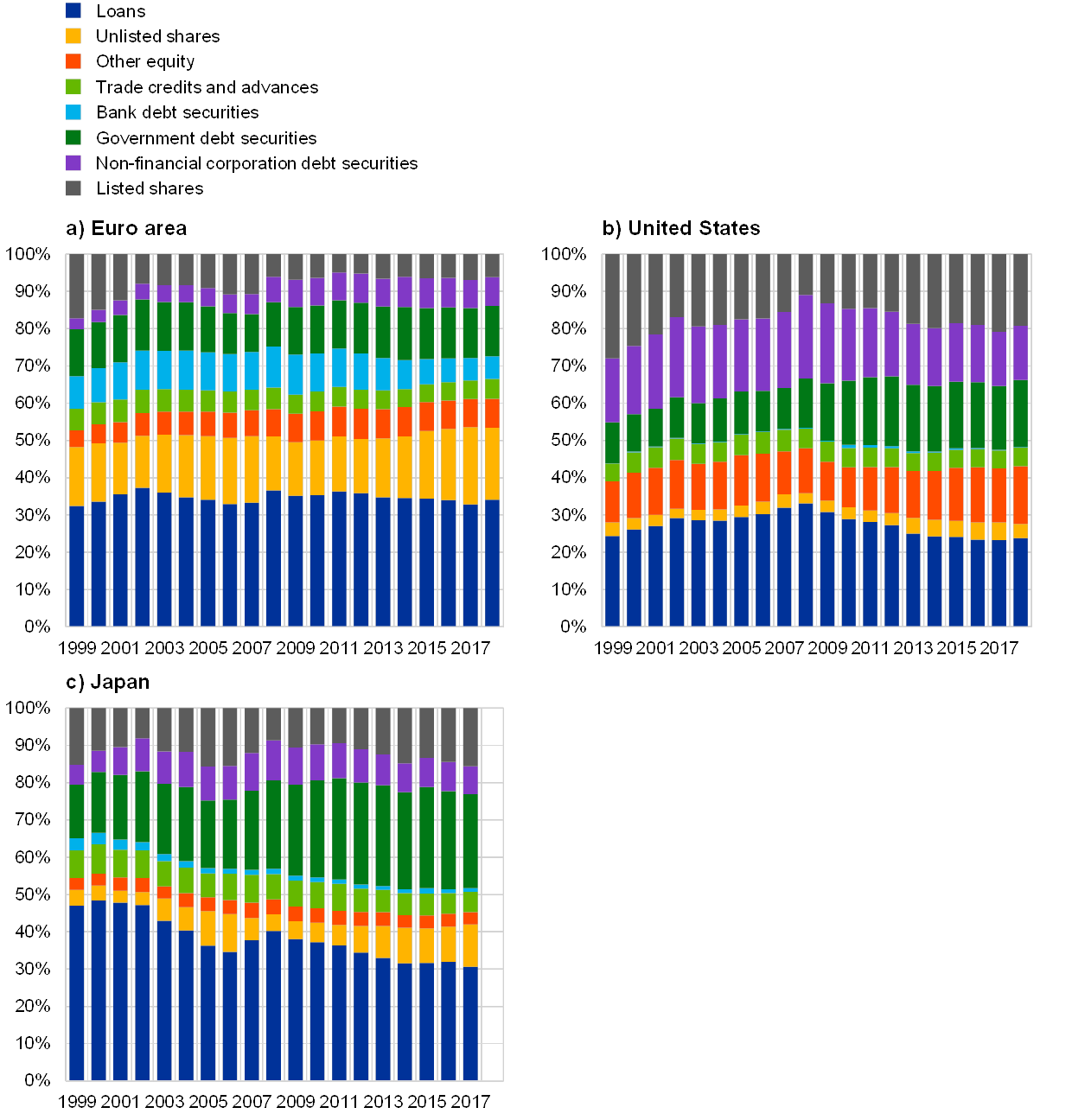

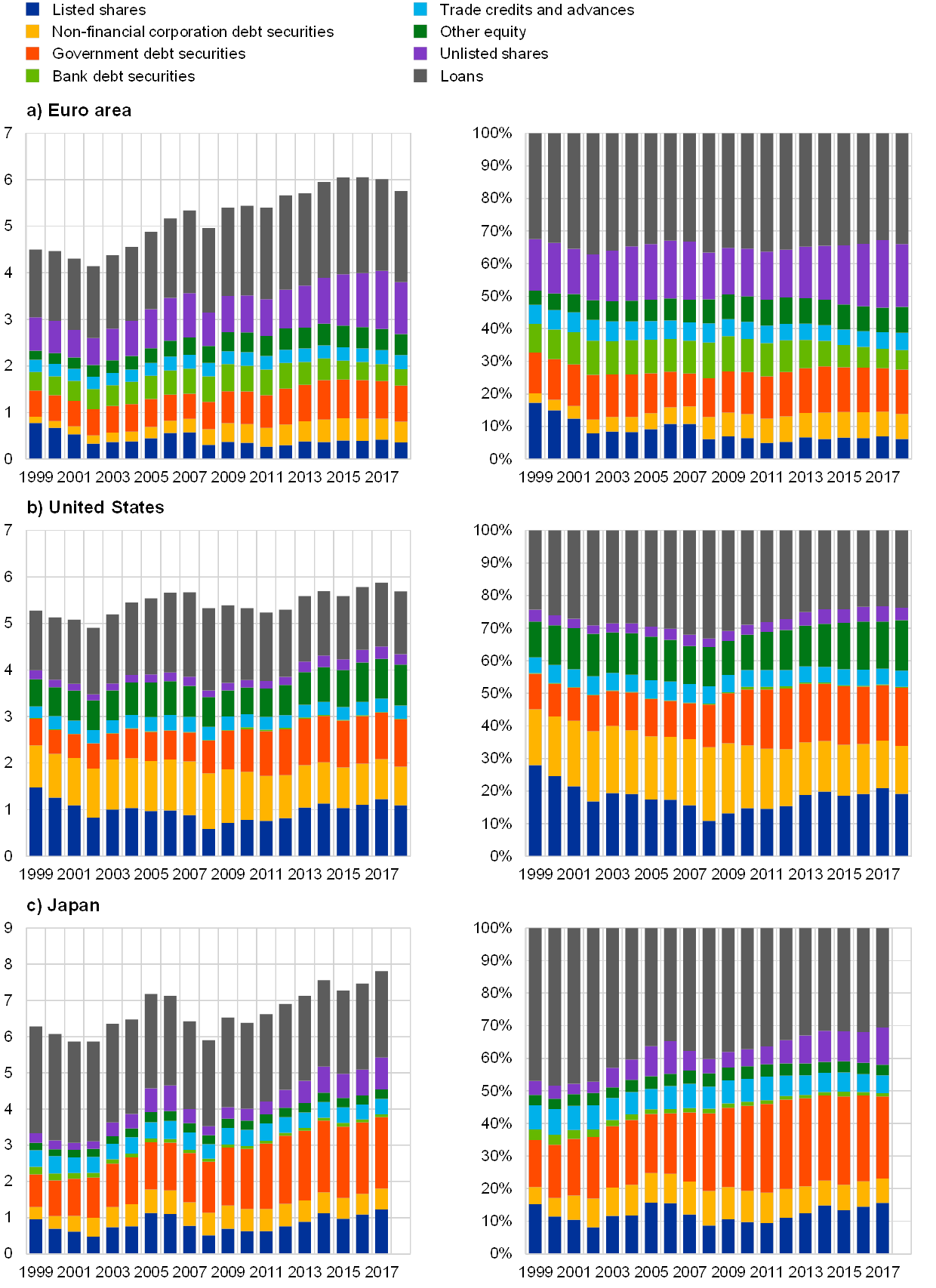

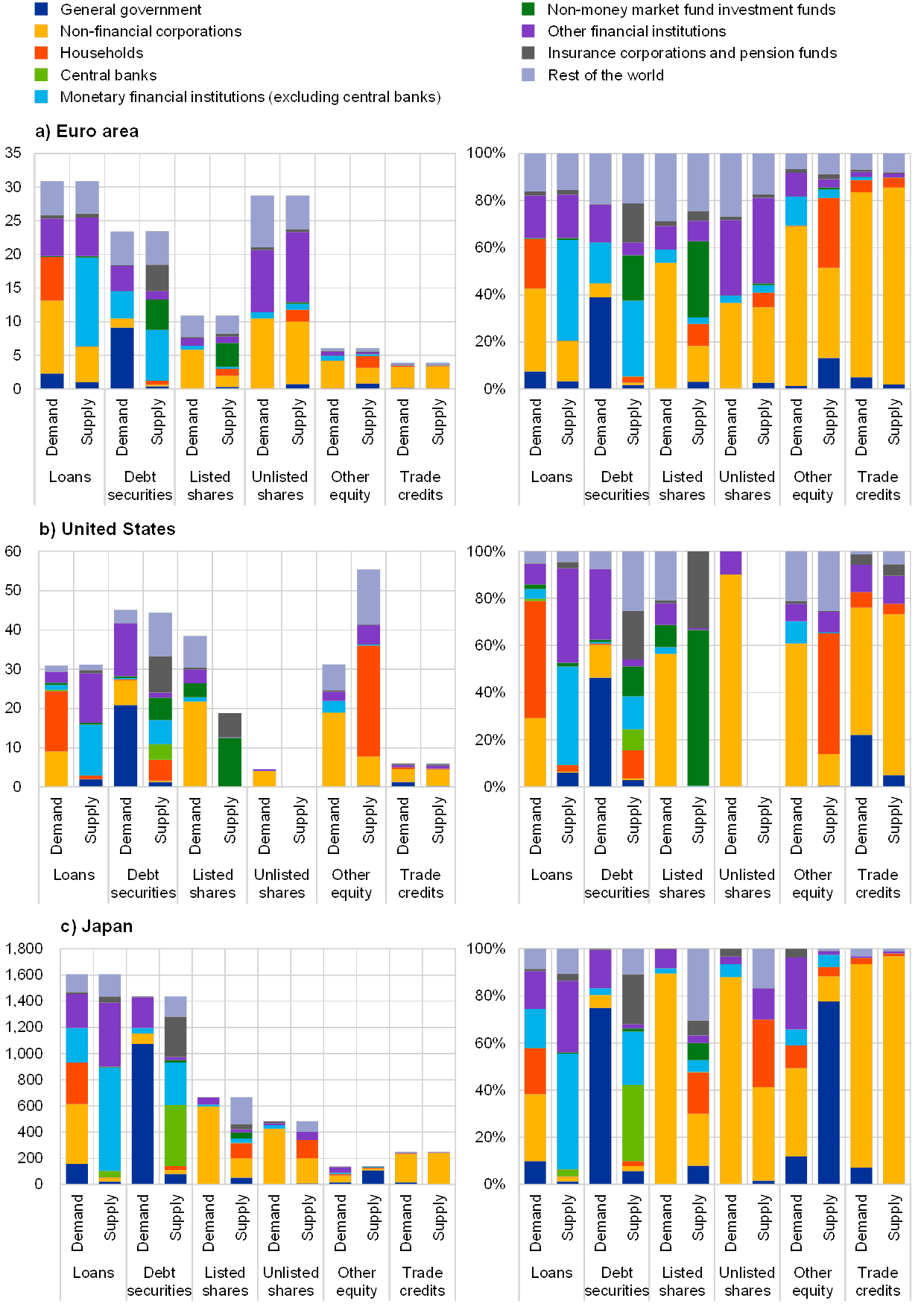

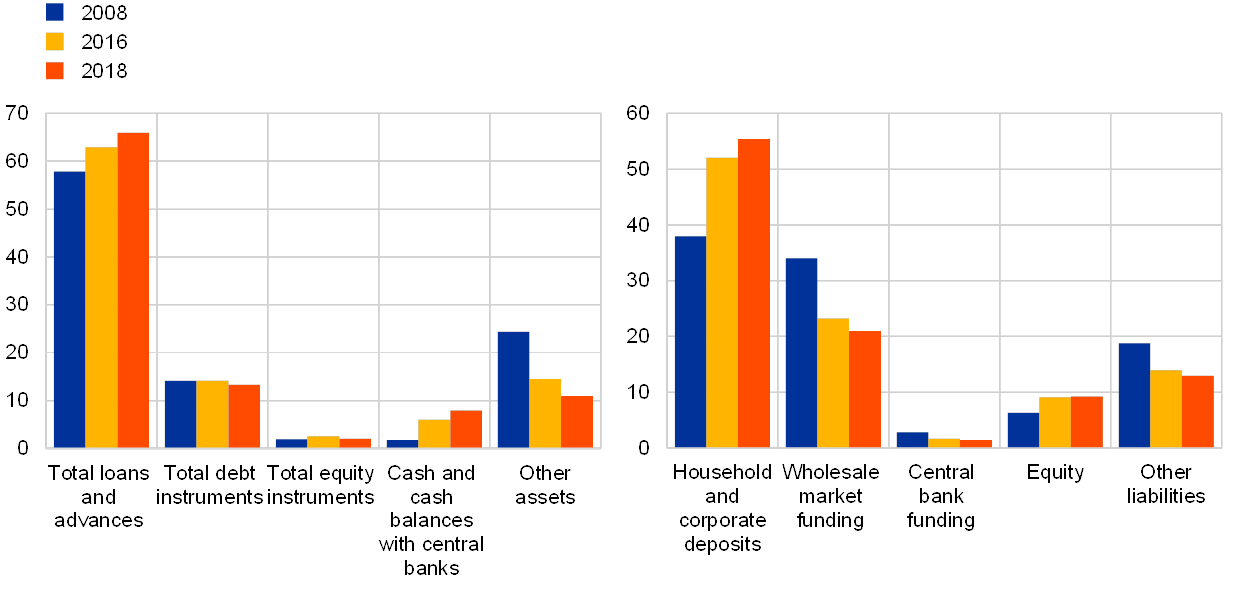

In terms of the roles of different financial markets, the euro area financial structure is characterised by a continuing dominance of non-marketable financing instruments, such as loans and unlisted shares. The second way of describing financial structure through the mixture of markets is via the relative importance of different financing instruments employed by the main economic sectors. Chart 1.2 details the relative shares of the main (on-balance-sheet) financial instruments in the aggregate financing of all economic sectors (households, firms and government, but excluding the external sector) for the euro area, the United States (US) and Japan. The three panels reveal some tangible differences, in line with the widespread view that Europe and Japan have more bank-based financial systems and the United States has a more capital market-based system. The euro area economy has particularly large shares of financing through loans and unlisted shares and the Japanese economy through loans and government debt securities. The US economy has a larger part of financing through listed shares and non-financial corporation (NFC) debt securities than the euro area or Japan (although the shares of loans and other equity are not small).

Only some marketable instruments, notably NFC debt securities, show a small medium-term upward trend in the euro area, while the amount of public equity remains relatively small. While the share of all equity instruments in total financing in the euro area is comparable to that in other countries, the proportions of different equity instruments are not. Financing through equity traded on public markets (listed shares) is relatively small, while financing through private equity (unlisted shares) is relatively large. In line with its bank-based system, the share of bank bonds – effectively financing loans (and leading to some double-counting in Chart 1.2) – is relatively large for the euro area compared with the US or Japan. At the same time, bank bond financing has somewhat declined after the financial crisis and direct corporate bond financing has increased, meaning that the latter has become larger than the former in the euro area. However, the slowly moving aggregate stocks displayed in Chart 1.2 do not suggest a generalised trend towards greater market-based financing, as financing through unlisted shares has broadly increased in tandem. They also mask significant cross-country heterogeneity in the relative importance of market-based instruments. If anything, Chart 2 in the first chapter of this report shows a mild decline for all sectors together over the last two decades. This may, however, have bottomed out recently, as the market-based financing of NFCs recovered after the crisis (probably because NFCs needed to compensate for bank deleveraging).

Chart 1.2

Financing structures of the euro area, US and Japanese economies by type of instrument

(percentages; annual data: 1999 -2018)

Sources: ECB for euro area and OECD for United States and Japan.

Notes: The chart is constructed from the liabilities of all economic sectors, excluding liabilities to the rest of the world, loans from NFCs (to net out intra-company loans in this non-consolidated data), currency and deposits, investment fund shares or units, entitlements from pension, insurance and standardised guarantee schemes, financial derivatives and employee stock options as well as other accounts payable. Other equity refers to equity claims that are not securities listed on an exchange and not unlisted securities, such as equity in incorporated partnerships, equity in limited liability companies whose owners are partners, capital invested in cooperative societies or investment by the government in the capital of public corporations whose capital is not divided into shares. Data for the United States and Japan are based on the global System of National Accounts (SNA) 2008. The European System of Accounts (ESA) 2010 underlying the euro area data is broadly consistent with the SNA 2008, although in some cases it may be more detailed.

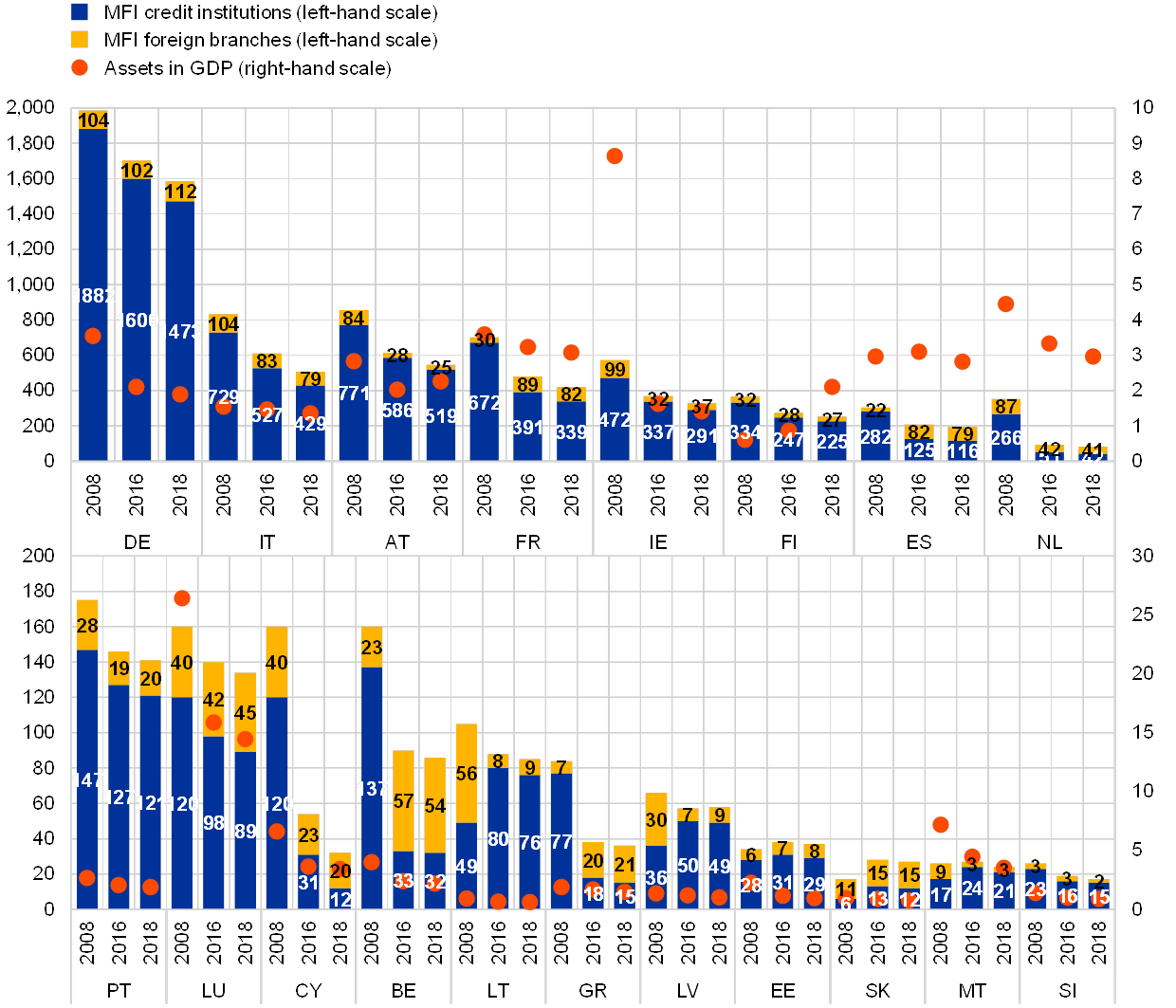

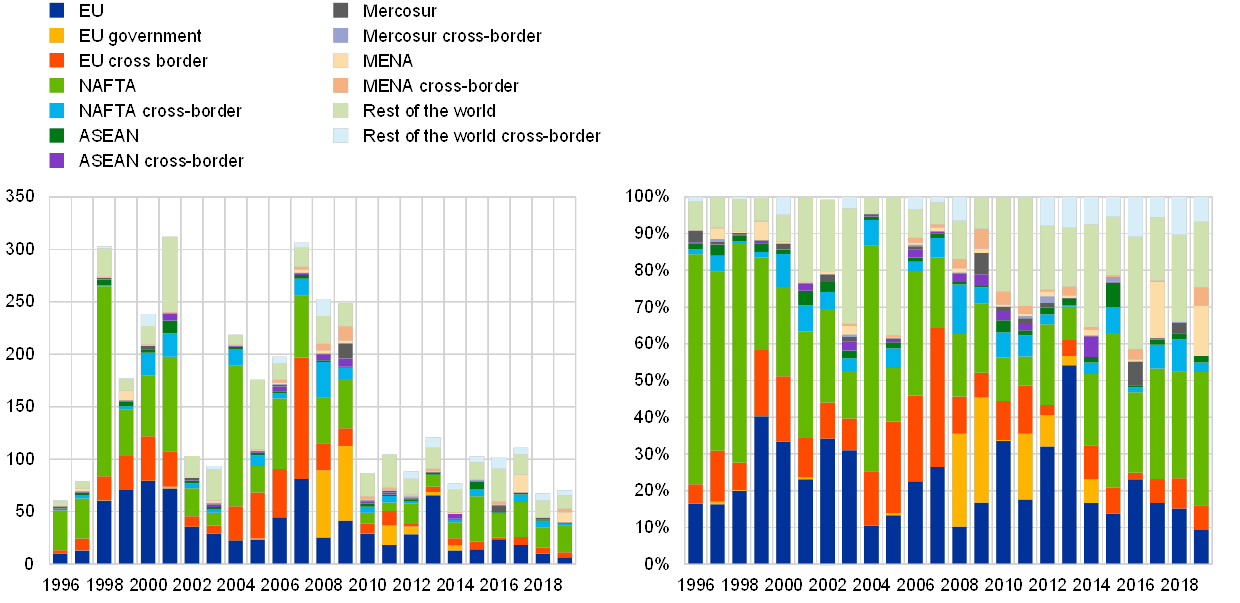

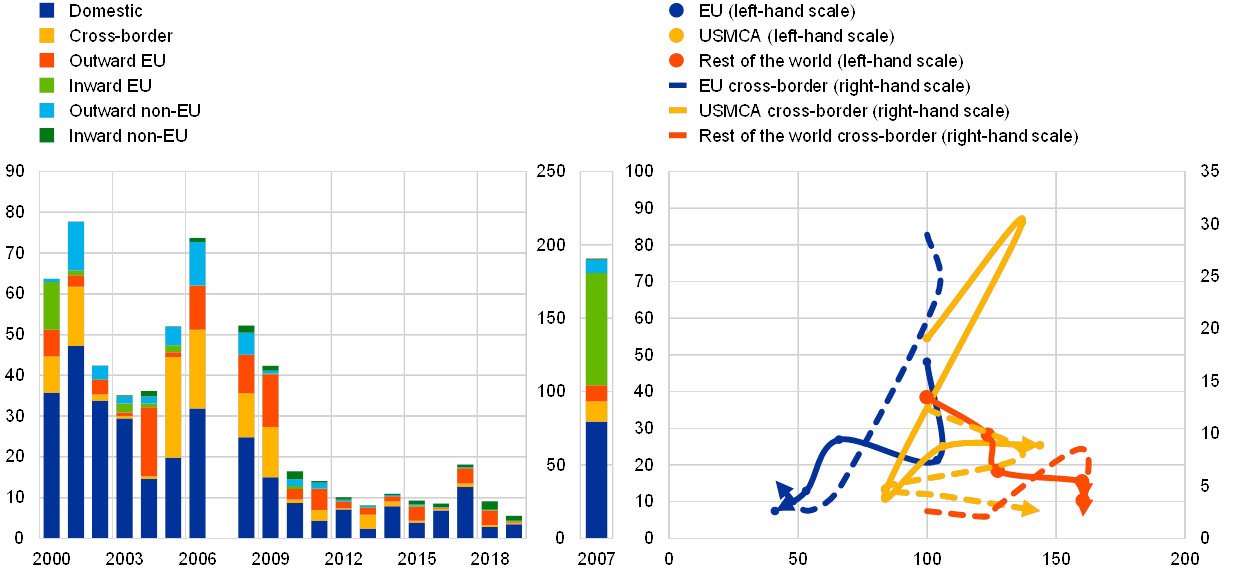

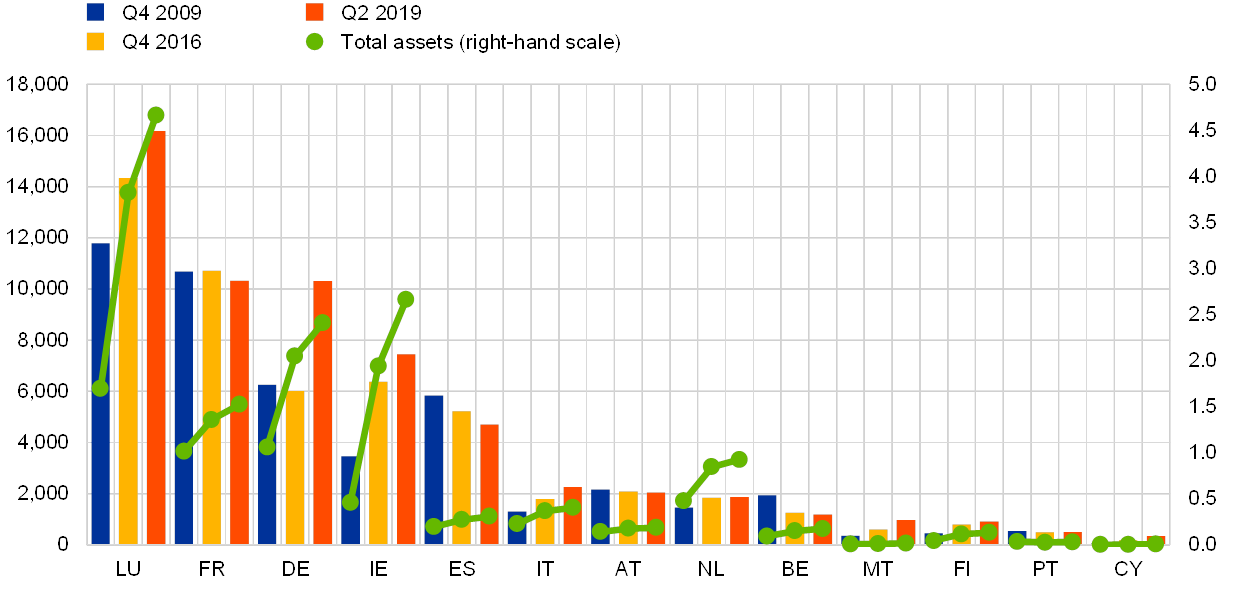

The post-crisis bank restructuring process in the euro area is continuing at a gradual pace, but the limited domestic and cross-border consolidation seems to also be a global phenomenon. Since the financial crisis, the euro area banking sector has been going through a gradual restructuring process, which involves the search for new business models, the adjustment to the revised regulatory regime, consolidation and the resolution of non-performing assets. The number of euro area banks continues to decline slowly, as consolidation has remained rather muted since the crisis, whereas the number of foreign branches has been broadly stable. Interestingly, Box 3 in the first chapter finds that subdued post-crisis consolidation dynamics are not specific to the euro area or the EU. Similarly, low domestic and cross-border bank merger and acquisition (M&A) activity since 2010 has also been observed in the other main free-trade areas around the globe, including the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA, the successor to the North American Free Trade Agreement or NAFTA) area and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) area.

One specific obstacle to bank consolidation in the euro area could be persistently low valuations and their underlying causes, in addition to other economic, business and regulatory factors. The single currency and the banking union could have been expected to result in a greater cross-border component of the bank consolidation process than in other regions of the world. But this is not the case. In addition to a series of economic, business and regulatory factors (including the still incomplete banking union) discussed in the 2018 ECB report on “Financial integration in Europe”, the box in this report points to declining valuations of euro area banks in the last few years as another important factor that may explain the lack of consolidation. The factors that might be behind the declining valuations include low profitability, problematic business models, high costs, unresolved non-performing exposures, and/or market misperceptions or mispricing. Such declining valuations have not been observed in the USMCA region or the rest of the world and seem to be specific to the euro area.

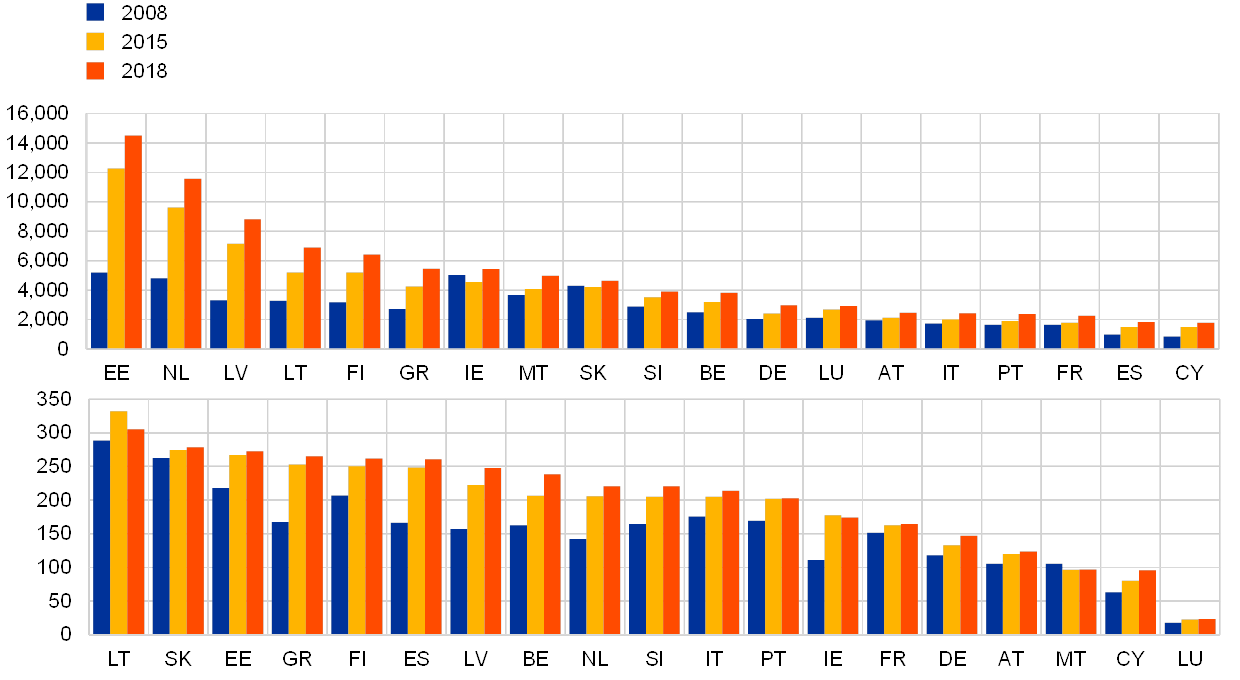

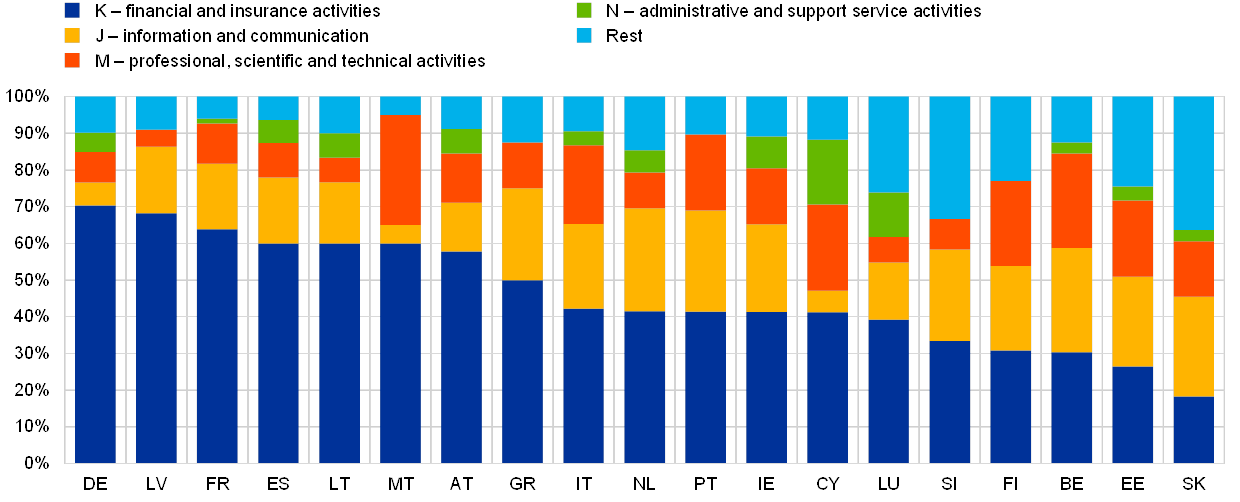

Following the dynamic creation of fintech entities over the last decade, the euro area now hosts about a fifth of all such entities worldwide – quite a number of which are located in smaller, “tech-savvy” euro area countries. One of the most dynamic developments in the financial structure of major economies has been the growth of fintech companies – companies that use technological innovation, in particular information technology, to support or provide financial services. Given the absence of a specific statistical reporting framework for fintechs so far, information about them is relatively limited and unsystematic. Based on a new but still experimental dataset collected by the ECB, the report indicates that – following a sharp acceleration in the creation of fintechs in the euro area since the middle of the first decade of the millennium – the 2,800 fintech entities domiciled in the euro area in 2018 constituted more than a fifth of all fintech entities worldwide. While large euro area countries host most fintech entities, there are some small and “tech-savvy” countries with significant fintech representation relative to their population (e.g. Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Lithuania and Luxembourg).

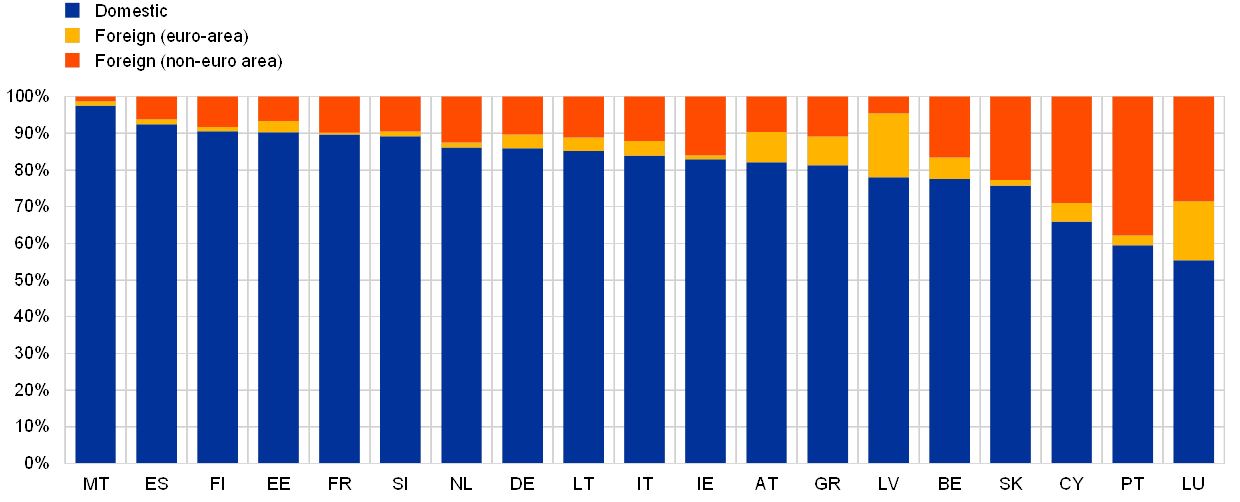

Understanding the economic benefits and potential risks of fintechs would be facilitated by integrating them as a separate class into the international and European statistical classification systems for economic activities. Following the typology of the European Banking Authority, the experimental dataset reveals that most entities are involved in payment, clearing and settlement services or in credit, deposit-taking and capital-raising services. But there are also significant numbers of entities involved in investment services and management or in credit scoring, compliance services and other (not further classified) financial technology. In terms of ownership structure, the largest shareholder group tends to be from the financial and insurance sector and the second largest group from the information and communication sector. In terms of the location of shareholders, most of the fintech entities are domestically owned. In order to provide a sound basis for monitoring fintech developments, for assessing their benefits and risks and for analysing their implications for the main central bank functions, it is important that they are properly integrated into the international and European statistical classification systems for economic activities. Monitoring and assessment would be facilitated if fintech activities were to become a separate class.

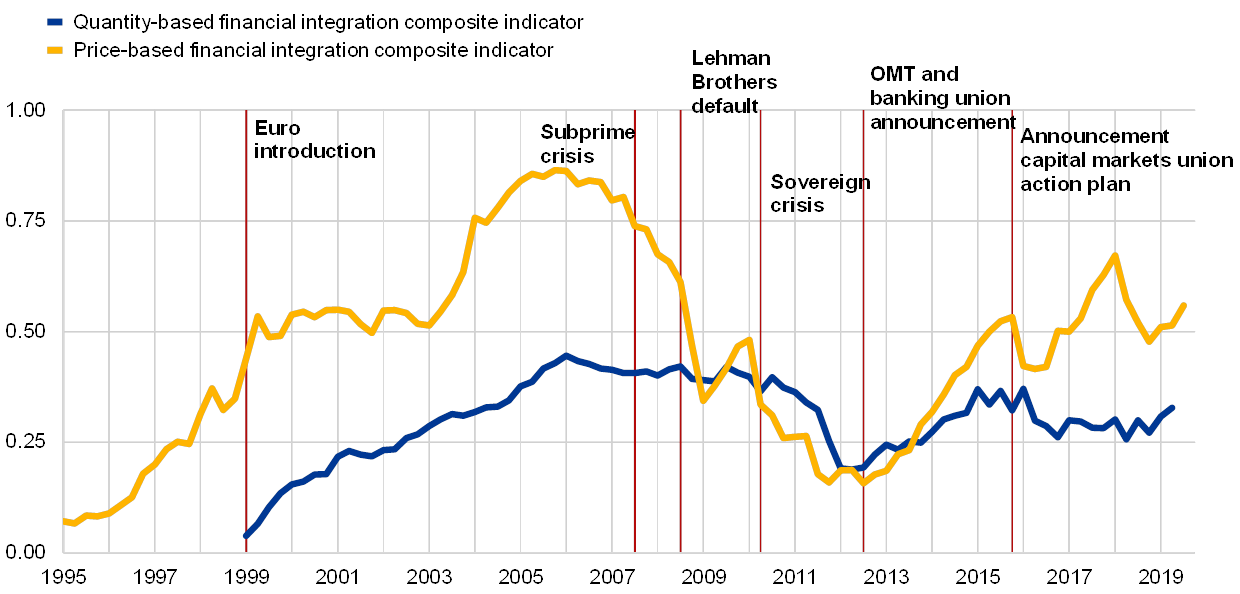

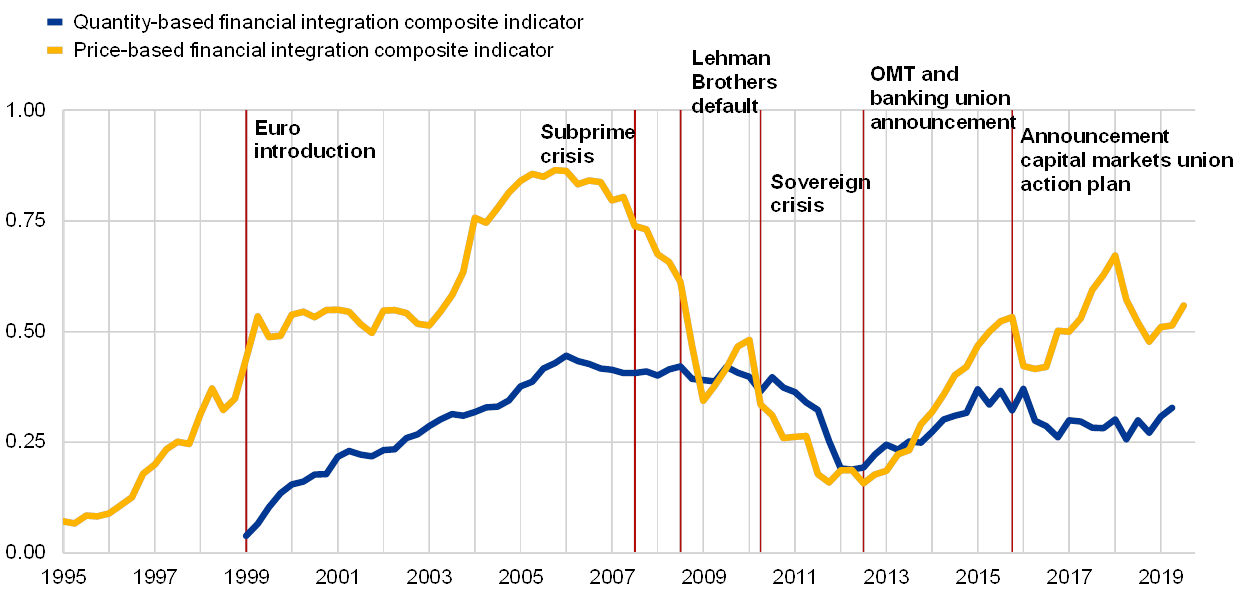

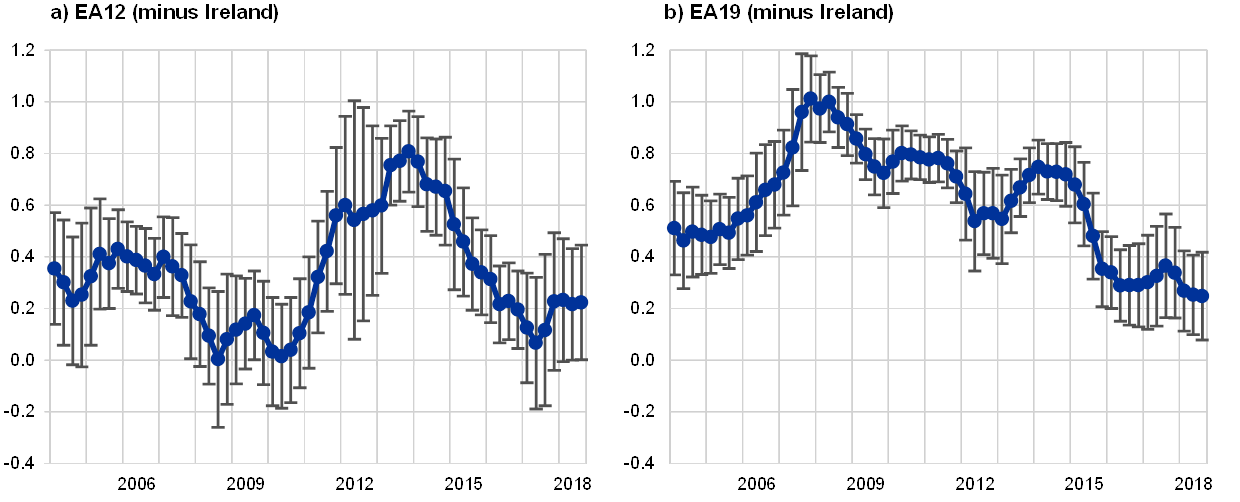

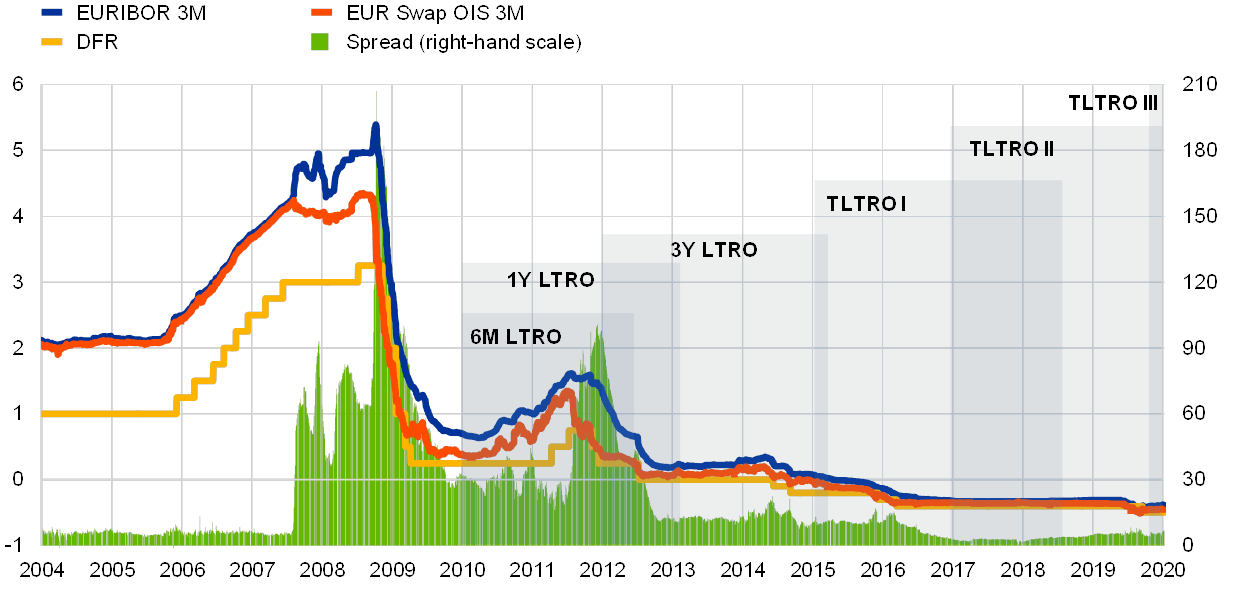

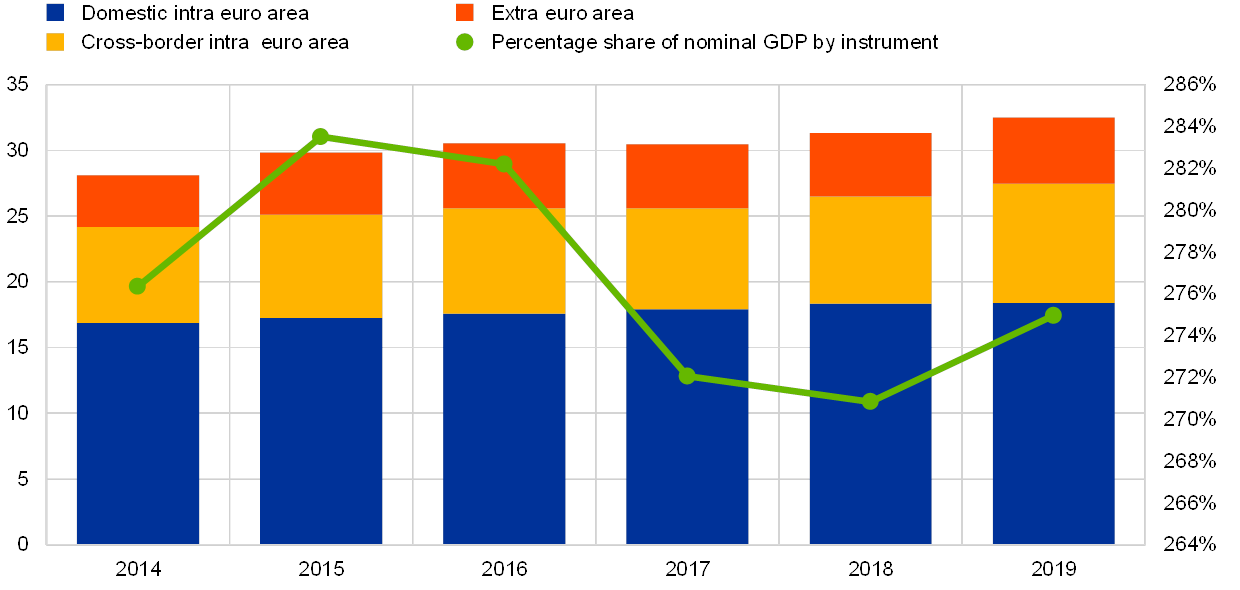

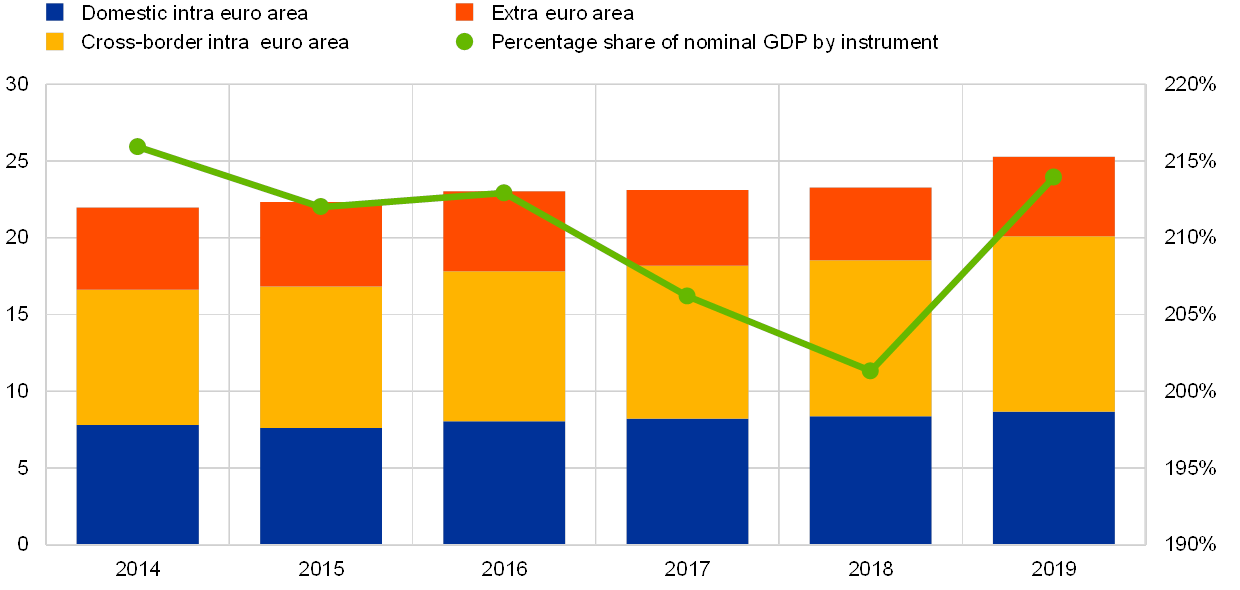

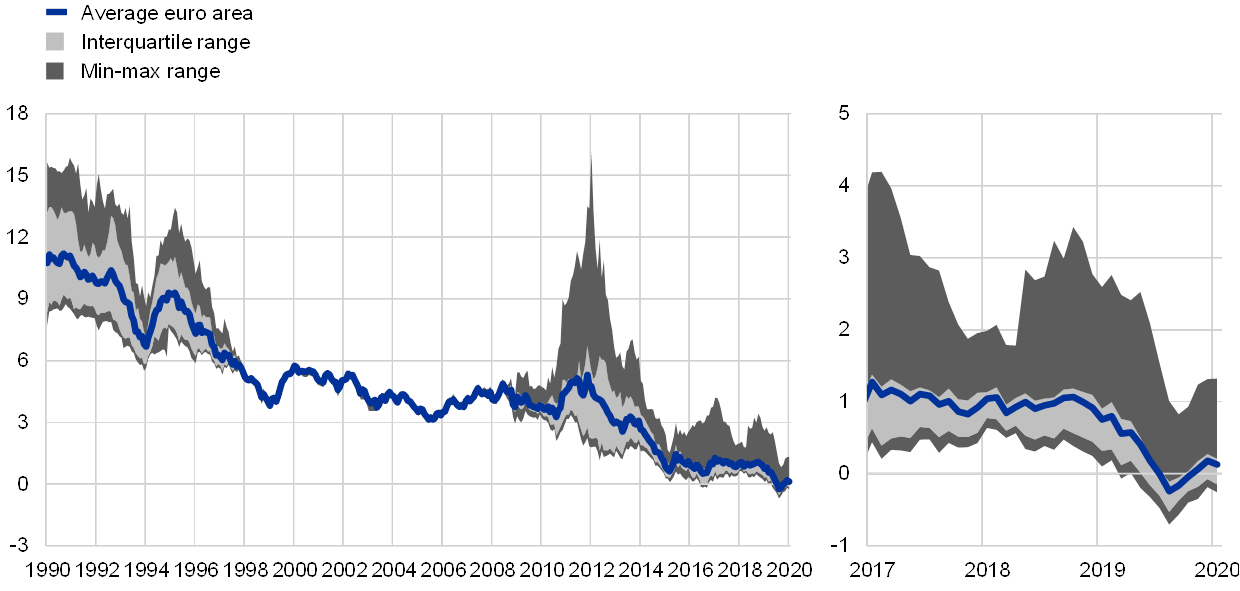

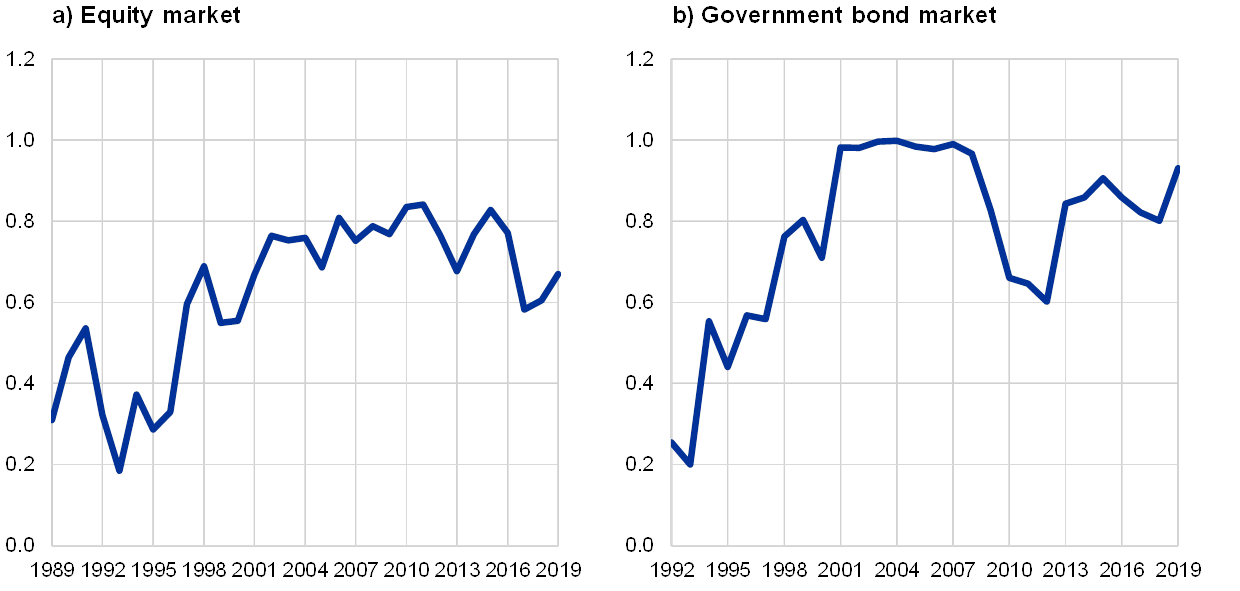

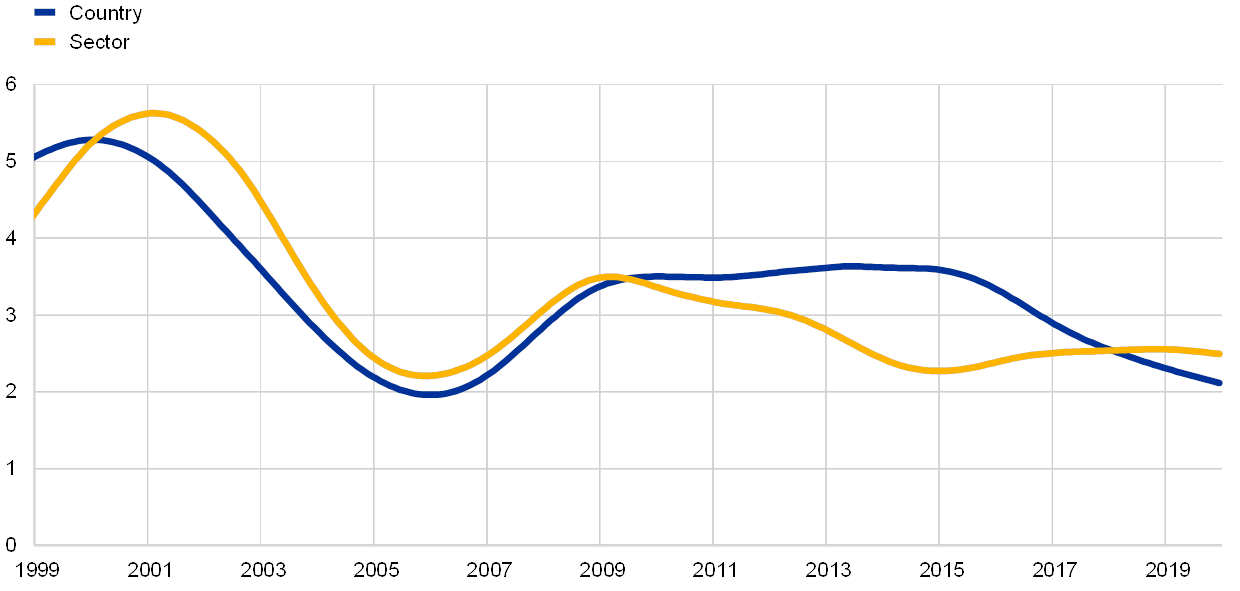

Following the strong post-crisis reintegration trend in the euro area until 2015, mixed developments in overall financial integration since then have been characterised by substantial volatility in price convergence and the stalling of growth in cross-border investment. The more advanced financial integration across euro area countries is, the more one can talk about a single market for financial services and the more adequate it is to look at financial structure and development in the euro area as a whole. The two composite indicators of financial integration displayed in Chart 1.3, which are designed to approximate the overall picture of euro area financial integration by combining information from the most important financial markets, still suggest discrepancies between integration as reflected in cross-border price differentials (the price-based indicator in yellow) and integration as reflected in cross-border investment (the quantity-based indicator in blue). Following the financial and sovereign debt crises both strongly recovered until 2015. Thereafter, however, the price-based indicator showed sizeable fluctuations, with the latest reading being only slightly above the 2015 peak. This volatility resulted in particular from changing cross-border bond yield differentials, related to emerging and dissipating political uncertainties in various euro area countries among other factors. Despite the generally supportive effects on financial integration from the ECB’s expansionary monetary policy, the quantity-based composite indicator was held down since 2015 particularly by modest cross-border interbank lending, as the injection of excess reserves implied by unconventional monetary policy measures – as expected – reduced counterparties’ need for cash. The slight pick-up of the quantity-based indicator for the latest observation, bringing it to similar levels as seen in 2004 and 2015, was driven by recoveries in cross-border interbank lending and bond holdings. A related indicator on cross-border finance in the euro area published by the Association for Financial Markets in Europe, which is based on a broader set of market segments and thereby less influenced by a single component, shows, however, a more continuous post-crisis recovery also in terms of quantities.[9]

Chart 1.3

Price-based and quantity-based composite indicators of financial integration

(quarterly data; price-based indicator: Q1 1995 – Q3 2019; quantity-based indicator: Q1 1999 – Q2 2019)

Source: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The price-based composite indicator aggregates ten indicators for money, bond, equity and retail banking markets, while the quantity-based composite indicator aggregates five indicators for the same market segments except retail banking. The indicators are bounded between zero (full fragmentation) and one (full integration). Increases in the indicators signal greater financial integration. From January 2018 onwards the behaviour of the price-based indicator may have changed due to the transition from EONIA to €STR interest rates in the money market component. OMT stands for Outright Monetary Transactions. For a detailed description of the indicators and their input data, see the Statistical Web Annex to this report and Hoffmann, P., Kremer, M. and Zaharia, S. (2019), “Financial integration in Europe through the lens of composite indicators”, Working Paper Series, No 2319, ECB, September.

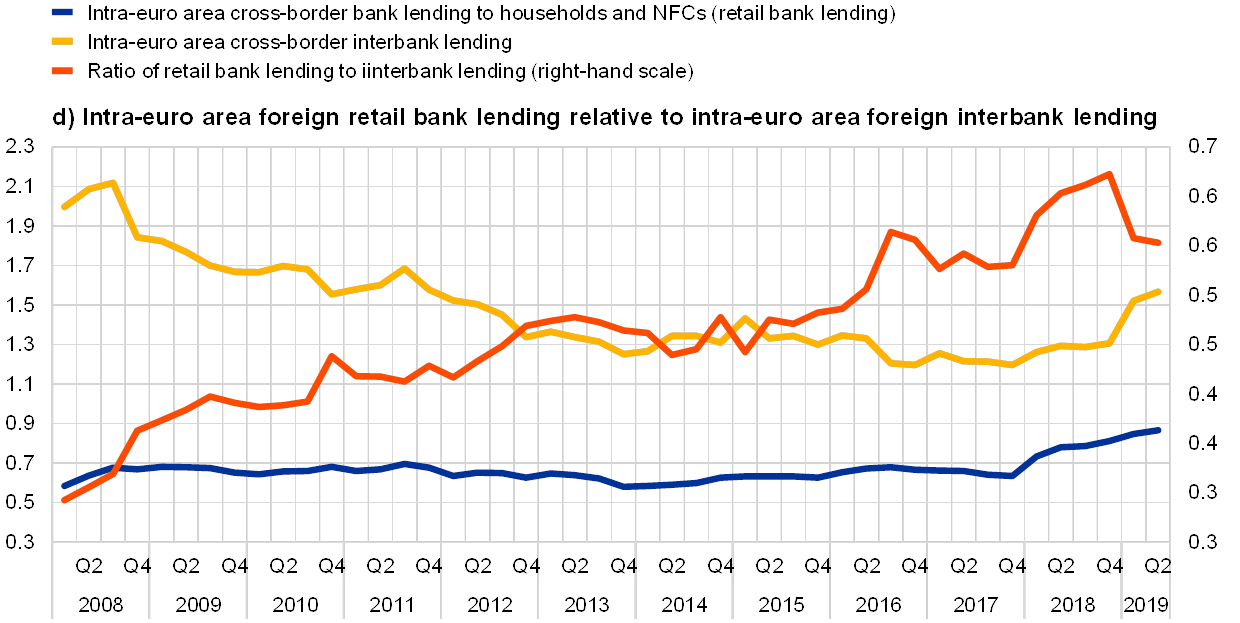

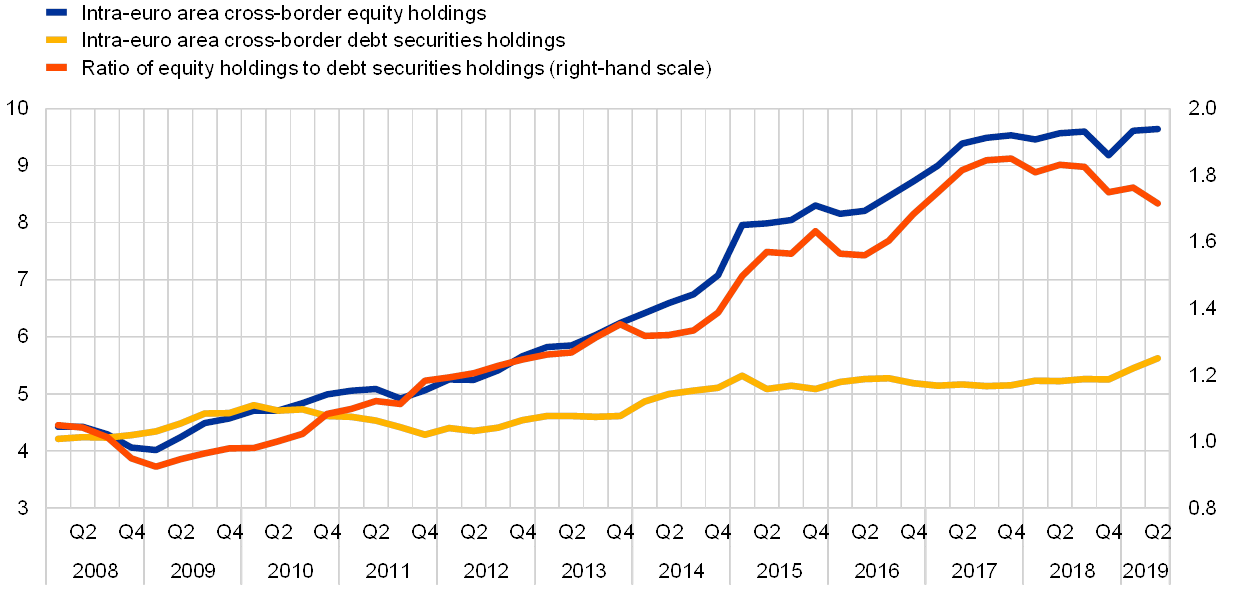

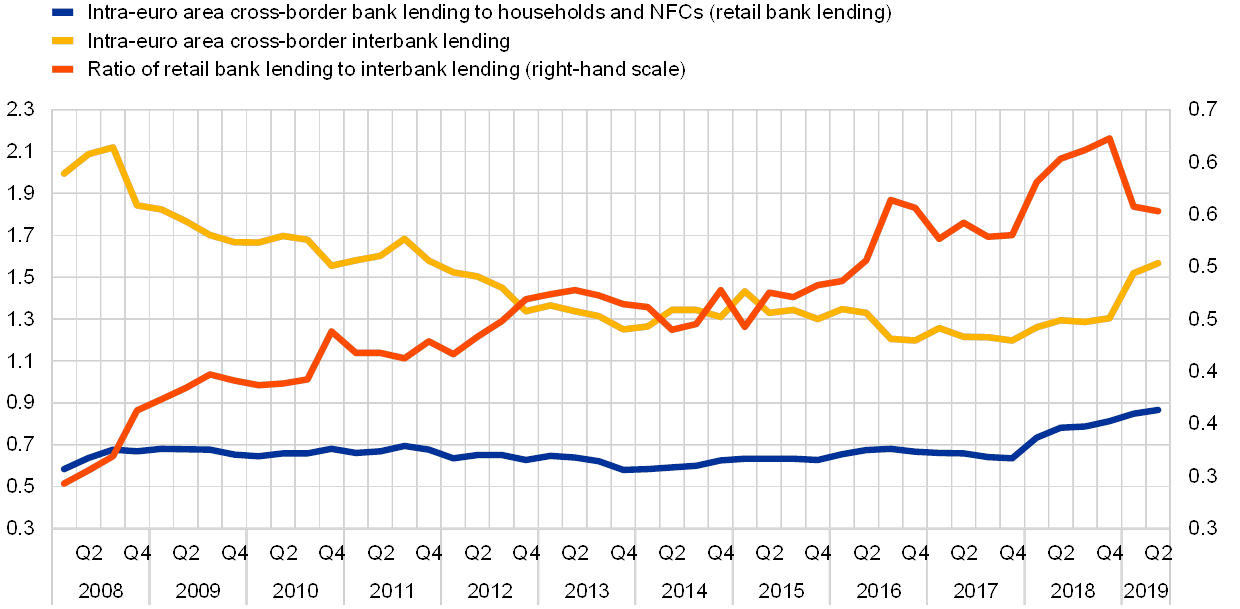

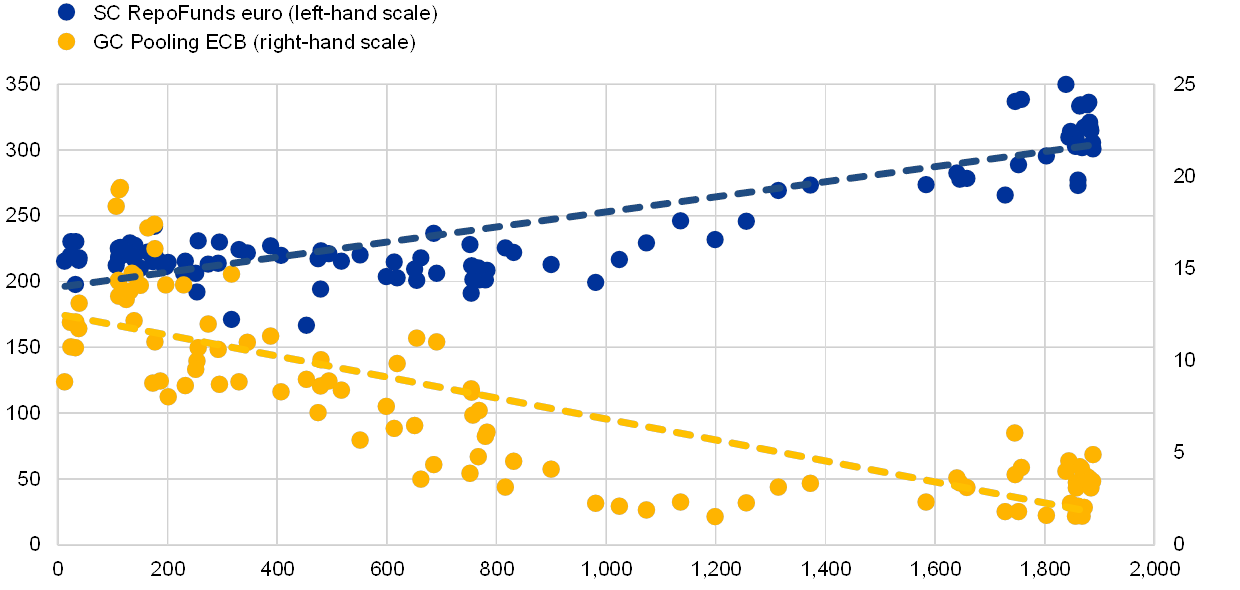

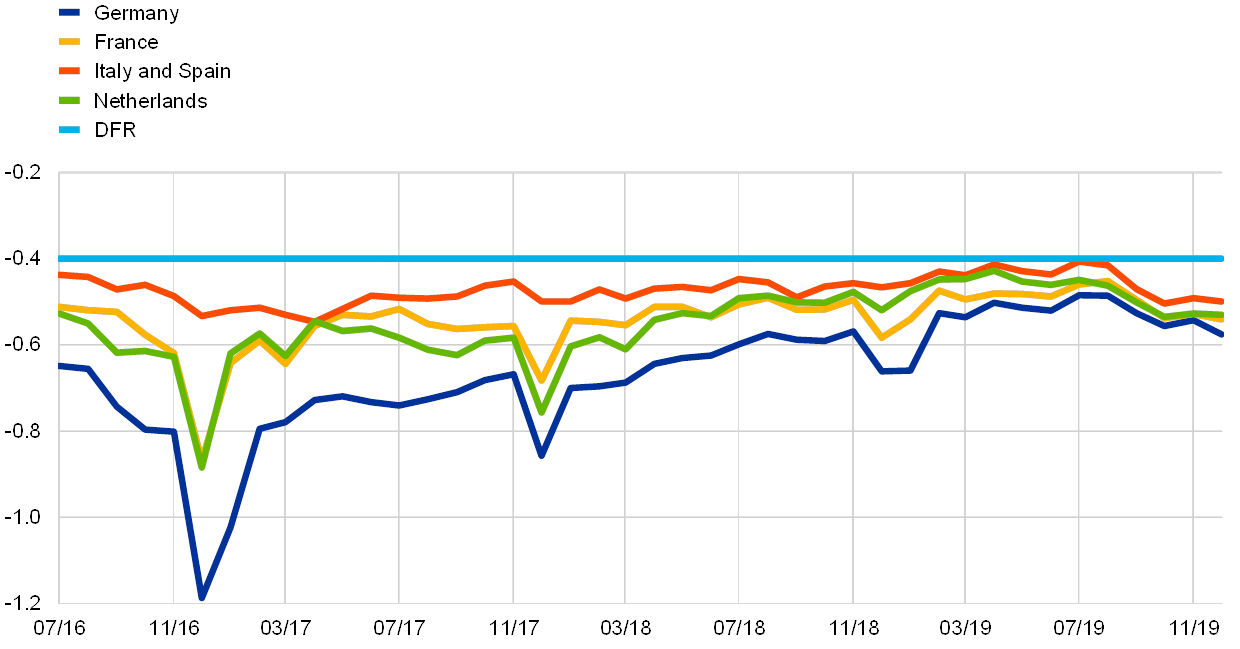

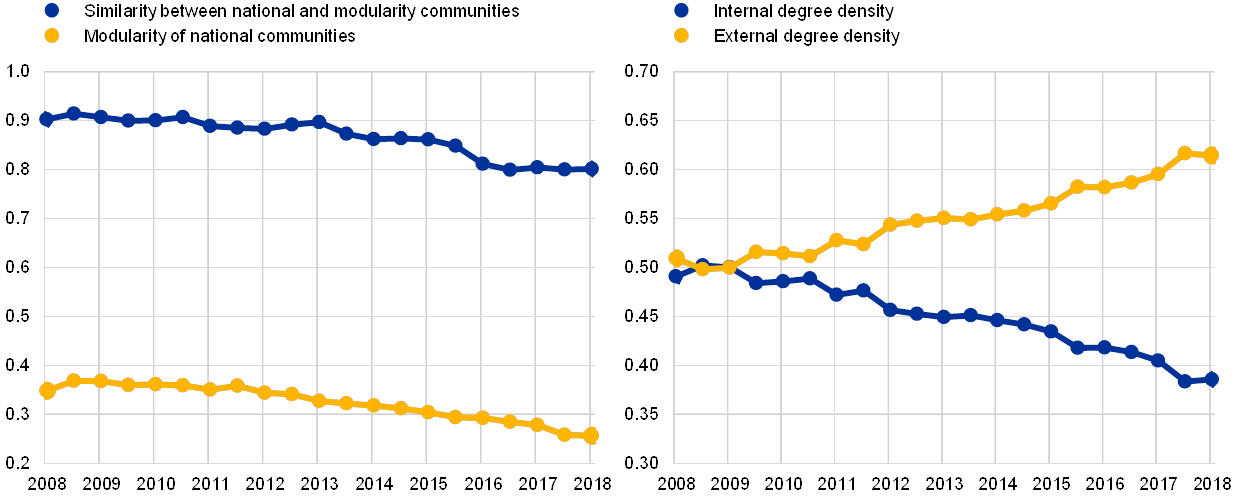

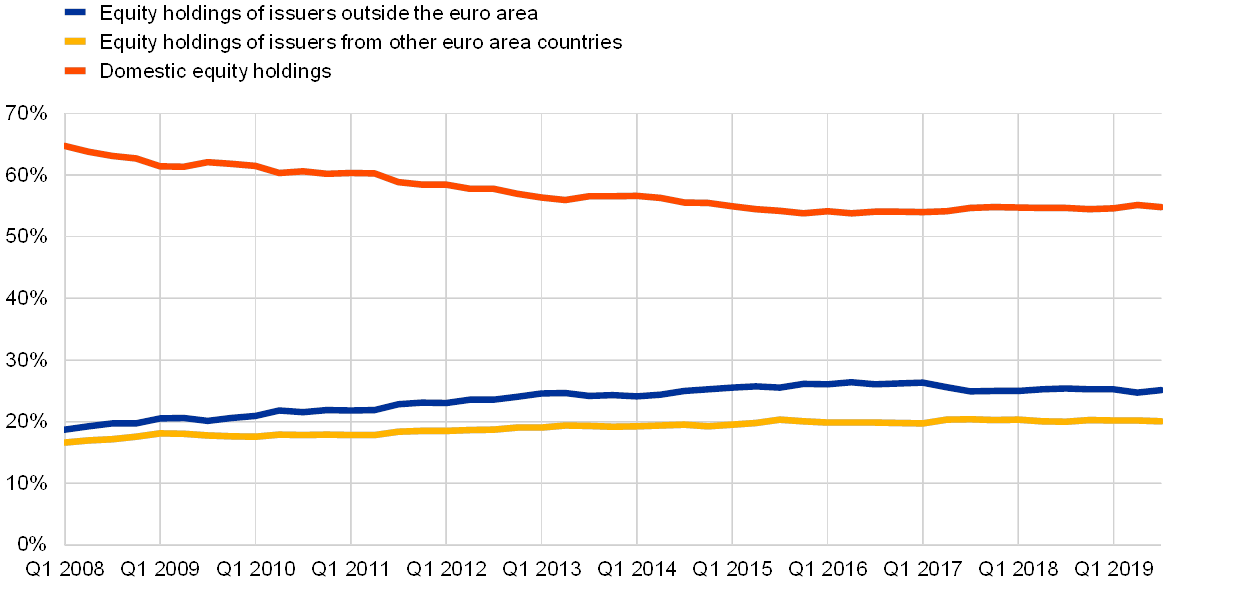

Favourable financial integration developments have been observed in the last few years, particularly, in large-value payment relationships, specific collateral repo market rates and, very gradually, bank retail lending volumes, but have mostly not been seen in equity markets. This report also identifies some specific integration developments in different financial markets. New research applying network methodologies to TARGET2 data indicates that the number of payment relationships that banks in Europe maintain with other TARGET2 banks of the same national community has steadily decreased in the course of the last decade, while new payment relationships with TARGET2 banks of other national communities have increased. This suggests increasing cross-border integration in the large-value payments area. In the secured euro money market, the specialness of repo rates for specific types of government bond collateral has diminished over the last two years, as indicated by the narrowing of their yield spreads below the ECB’s deposit facility rate for countries like France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. At the same time, euro area cross-border bank retail lending increased, albeit rather gradually and from a relatively low level (see the blue line in panel (d) of Chart 1.4). Euro area equity returns and holdings across countries (see the blue line in panel (a) of Chart 1.4) no longer point to further increases in stock market integration and, by some measures, suggest incipient signs of re-fragmentation. This is in line with the slowing and less uniform economic recovery, as well as political uncertainties in some euro area countries.

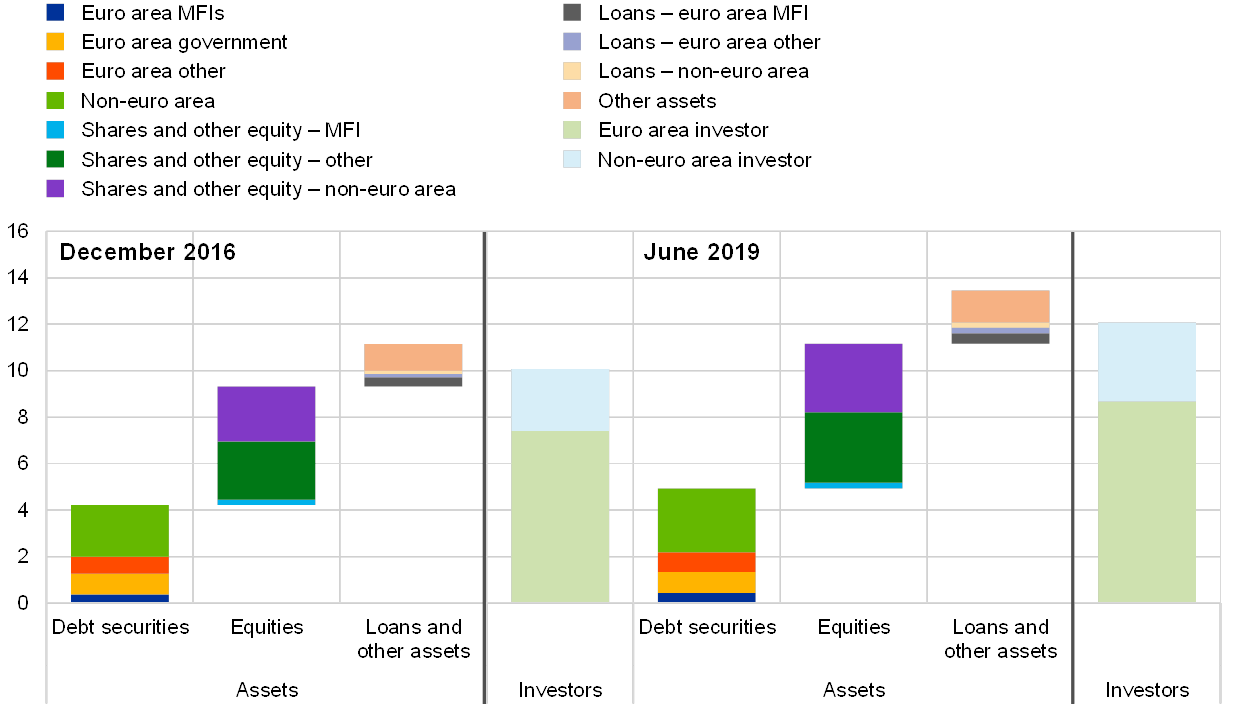

When considering measures of home bias in euro area equity and bond fund holdings that do not distinguish between investor and fund domiciles, it is necessary to be careful not to underestimate quantity-based financial integration. Special Feature C directly links fund investors’ countries of origin with the origins of their fund-specific equity and bond holdings. The corresponding home bias measure is considerably lower than measures taking the fund’s domicile as the investment origin. This finding can be explained by the sizeable share of fund investments that euro area investors hold in financial centres (e.g. Ireland or Luxembourg). The funds in these centres tend to have more diversified portfolios than funds domiciled outside financial centres. Therefore, when considering home bias measures that do not fully account for investor origin, one has to be careful not to underestimate quantity-based integration.

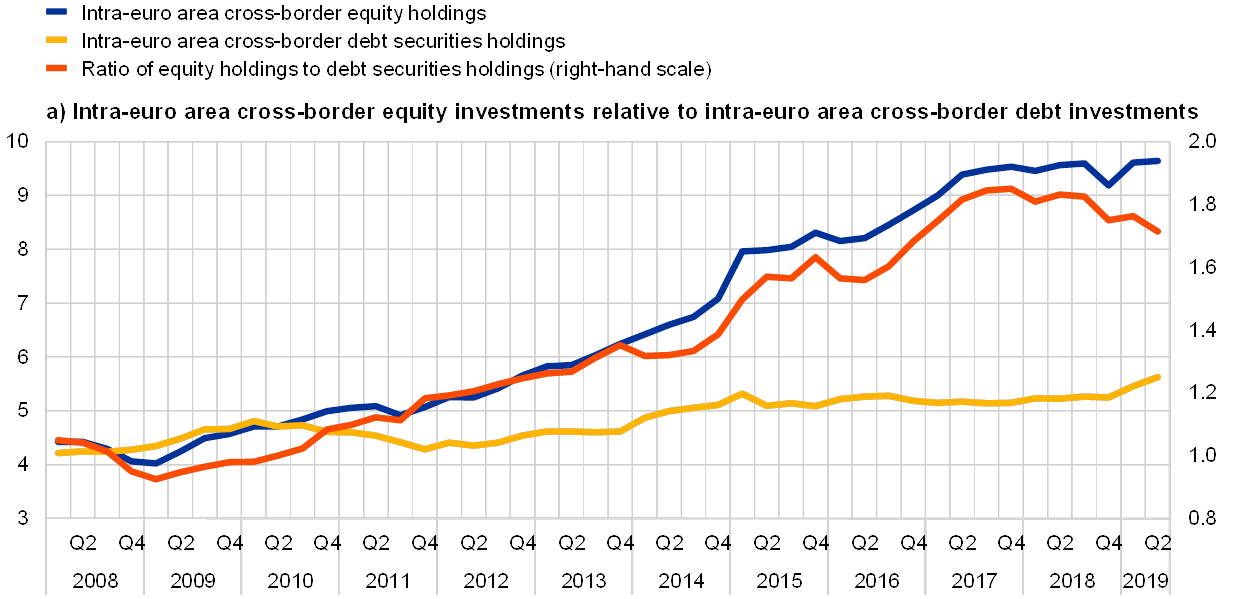

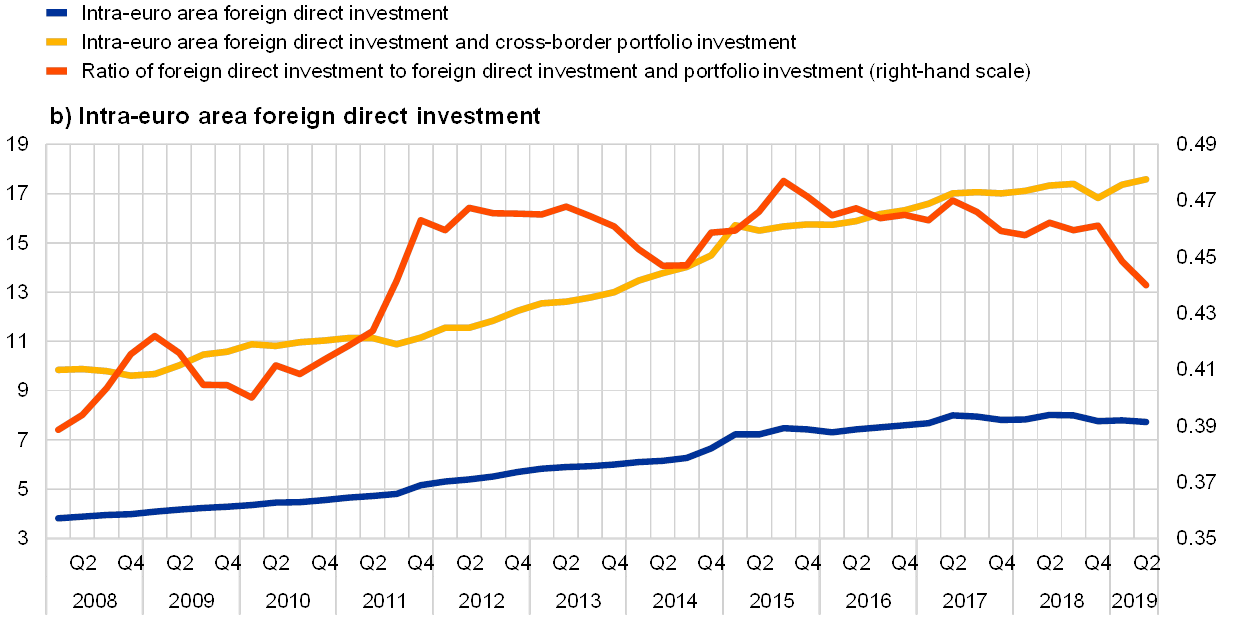

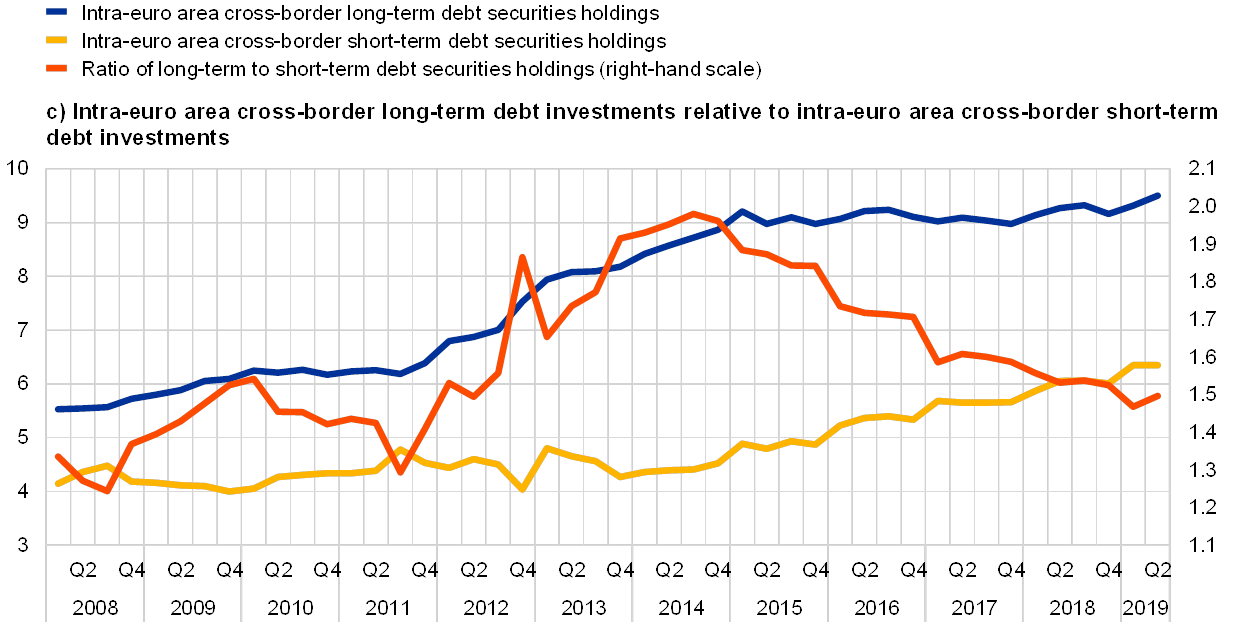

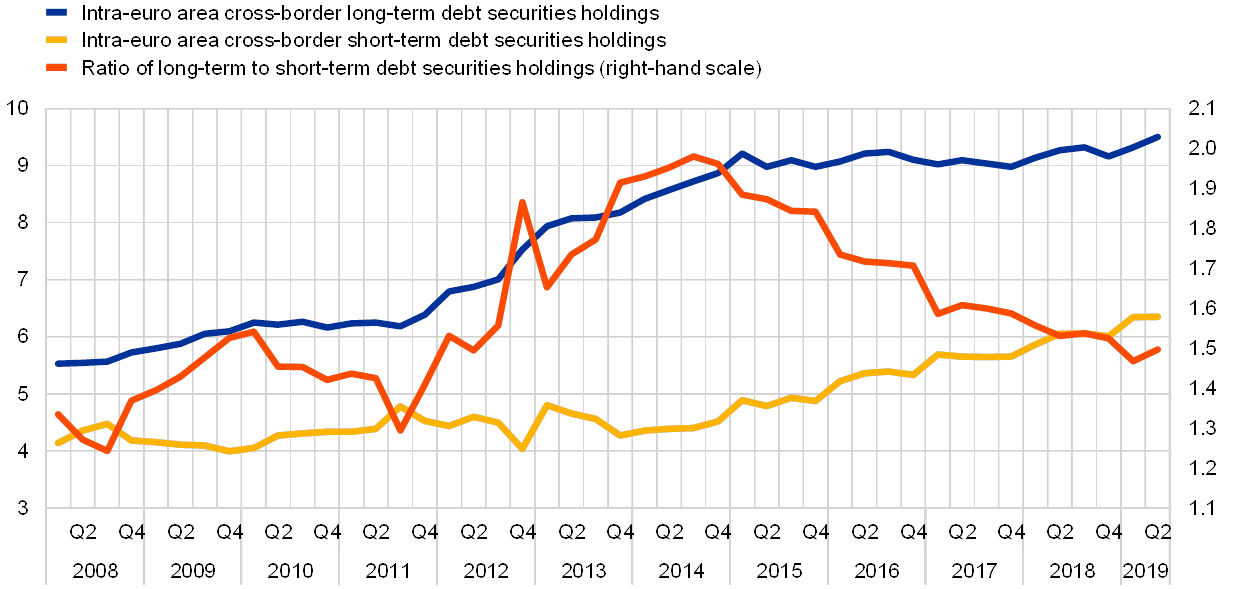

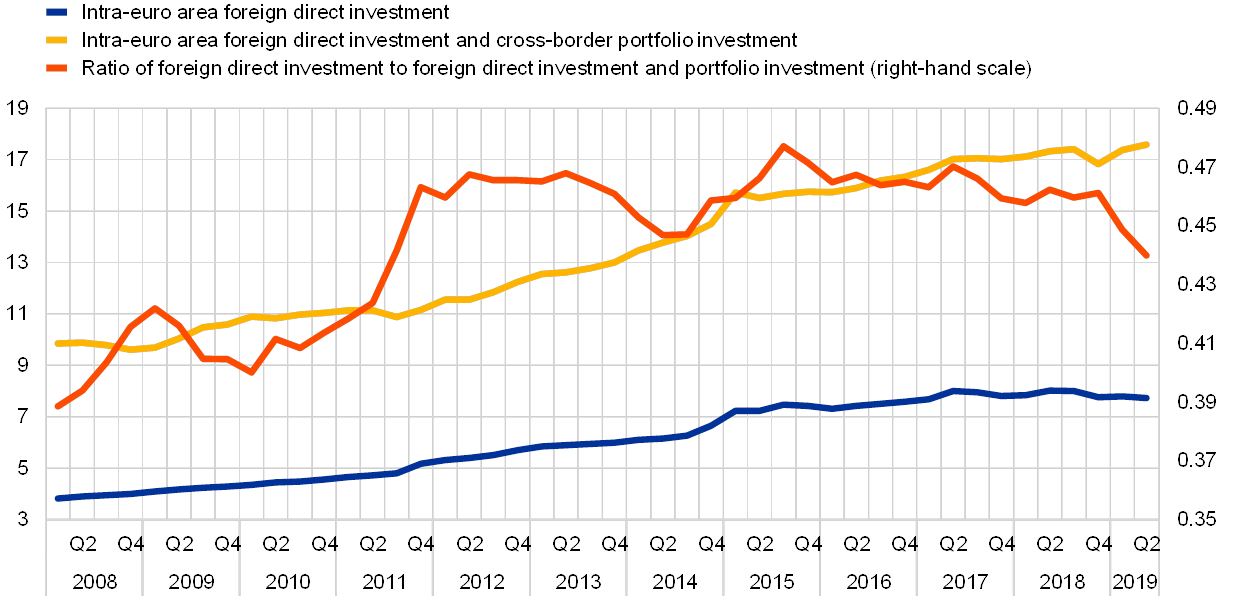

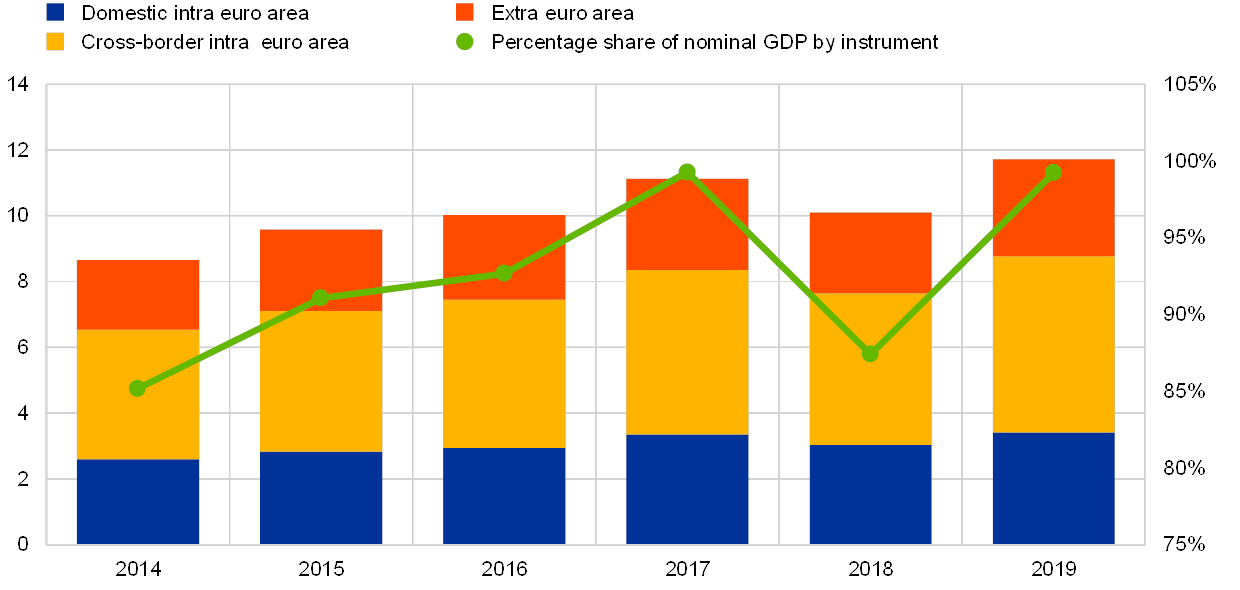

The significant post-crisis improvements in the resilience of euro area financial integration may have levelled out and it should be monitored that increasing cross-border short-term debt investments and decreasing cross-border foreign direct investment (FDI), if they continue, do not lead over time to pockets of vulnerability to shocks. Chart 1.4 shows the four indicators that the ECB monitors to assess the resilience of euro area financial integration (i.e. that the improvements in financial integration since the financial and sovereign debt crises do not unravel should severe shocks strike). For example, one type of vulnerability could emerge from over-proportionate shares of “runnable” instruments, such as interbank loans or short-term debt securities. First, panel (a) of Chart 1.4 may suggest that the ratio of cross-border equity investments to cross-border bond investments in the euro area peaked in 2017 and 2018. Second, panel (b) shows that FDI within the euro area as a share of cross-border direct investment and portfolio equity investment hovered around similar levels since 2011 and started to decline towards the end of 2018.[10] Third, panel (c) shows that since 2014 cross-border short-term debt investments have grown at a faster rate than cross-border long-term debt investments in the euro area. Fourth, panel (d) shows that during 2019 the rather gradual increase in cross-border retail bank lending in the euro area was more than offset by the recovery in cross-border interbank lending. While the reversals still tend to be rather small and, perhaps with the exception of short-term debt, not particularly protracted as yet, it seems advisable to continue monitoring developments in these resilience indicators.

Chart 1.4

Indicators of the resilience of financial integration in the euro area

(left-hand scale: EUR trillions; right-hand scale: ratio)

Sources: (a) ECB and ECB calculations; (b) ECB; (c) ECB, ECB calculation based on balance of payments data and Eurostat; (d) ECB.

Notes: (a) The blue line shows the total amount of equity holdings by euro area investors (all sectors) issued by residents of other euro area countries. The yellow line shows the total amount of debt securities holdings by euro area investors (all sectors) issued by residents of other euro area countries. The orange line shows the ratio of the two. For both equity and debt investments, the total refers to the sum of intra-euro area cross-border and domestic asset holdings. (b) The blue line shows the total amount of intra-euro area foreign direct investment. The yellow line shows the sum of intra-euro area foreign direct investment and intra-euro area cross-border portfolio investment. The orange line shows the ratio of the two. (c) The blue line shows the total amount of long-term debt (with a maturity of more than one year) issued by euro area countries and held by residents of other euro area countries. The yellow line shows the total amount of short-term debt (with a maturity of less than one year) issued by euro area countries and held by residents of other euro area countries. The orange line shows the ratio of the two. (d) The blue line shows the total amount of intra-euro area cross-border bank lending to households and NFCs, i.e. retail bank lending. The yellow line shows the total amount of intra-euro area cross-border lending between MFIs, i.e. interbank lending. The orange line shows the ratio of the two. For more discussion on the interpretation of these indicators, see Special Feature A “Financial integration and risk sharing in a monetary union” in the 2016 ECB report on “Financial integration in Europe”.

(left-hand scale: EUR trillions; right-hand scale: ratio)

(left-hand scale: EUR trillions; right-hand scale: ratio)

(left-hand scale: EUR trillions; right-hand scale: ratio)

2 Selected policy issues for financial structure and integration

A number of the features of and developments in euro area financial structure, development and integration mentioned above underline the importance of completing the European banking union and making further progress with the European capital markets union. Concerning CMU, the share of marketable financing instruments has not increased since the introduction of the euro. In particular, compared with other countries, there is scope to raise the share of public equity in total corporate financing. Furthermore, the euro area private equity markets should become a more dynamic source of risk capital, which would give rise to better growth opportunities for young and innovative companies. At the same time, the relatively strong growth of non-bank financial intermediaries suggests the need to contain transformed or new financial stability risks that may emerge and ensure a level playing field with banks. In order to maintain the resilience to shocks of the capital market integration achieved so far, it seems desirable that the slight declines in cross-border equity holdings and in FDI (to the extent that the latter was not a temporary effect of US multinationals repatriating foreign earnings) do not continue and that cross-border long-term debt investments resume to grow faster than short-term debt investments. Overall, the level of financial integration reached in the euro area is not satisfactory. For the effective functioning of the banking union, it would be good if the only very gradual increases of cross-border bank retail lending in the euro area continued and strengthened, enhancing the resilience of banking integration and increasing private credit risk sharing among euro area countries. These effects are much more likely to materialise with further cross-border bank consolidation among euro area countries. Therefore, obstacles to cross-border bank M&As should be addressed. In this regard and also more generally – including for financial stability purposes – further progress in completing the banking union is highly desirable.

The European Commission and the Economic and Financial Affairs Council of the EU (ECOFIN Council) have started initiatives to make a second set of measures to develop CMU following the 2015 Action Plan a priority for this legislative cycle. By the end of 2019, 11 out of 13 proposals included in the Commission’s CMU Action Plan announced in September 2015 had been adopted. As of January 2020, six of these legislative measures were already effective, with the remaining measures to gradually become effective up to mid-2022. While the adoption rate is relatively high, it also needs to be acknowledged that the ambition of some initiatives had to be lowered significantly in order to enable agreements among the European co-legislators. In the light of the above and other features of and developments in the EU financial system, various reports by policymakers and market participants have called for a second set of actions, partly reorienting CMU and taking it to the next level. Accordingly, the ECOFIN Council indicated its interest in putting CMU high on the political agenda and the Commission expressed its intention to make CMU a centrepiece of this legislative cycle. For example, the Commission has set up a High-Level Forum on capital markets union composed of experts from different industry sectors, which is working on proposals for concrete measures that could be included in the next CMU Action Plan. This work is currently focusing on how to create an ecosystem that enables more cross-border capital raising, how to develop a European capital market architecture and how to achieve greater retail investor participation, as well as on the related aspects of the transition to sustainable and digital economies.

The ECB strongly supports the new CMU initiatives, stressing for example the importance of further improving and harmonising insolvency frameworks and of further developing public and private equity markets in the EU. Given the benefits of more developed and integrated capital markets for the transmission of its monetary policy, for financial stability and for deepening EMU, the ECB strongly supports such efforts to further develop CMU. It stands ready to provide its views and advice on which policy measures would be most desirable. For example, already in the 2018 report on “Financial integration in Europe” the ECB emphasised the great importance of further improving and harmonising insolvency frameworks and of further developing public and private equity markets in the EU. Apart from generally fostering capital market integration and development, the key objectives of CMU should be to contribute to a wide choice and the stability of funding sources for households, firms and governments, to economic growth by supporting start-ups and promoting the scaling-up of young and innovative companies, and to more private financial risk sharing across euro area countries.

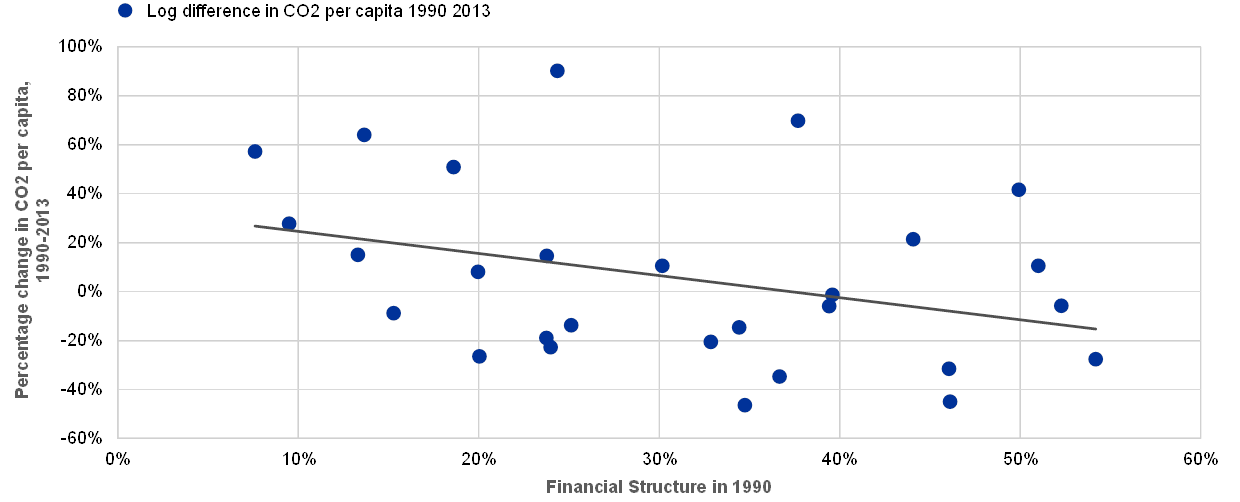

An emphasis on the further development of equity markets in the next set of CMU measures could, among other benefits, make an important contribution over time to de-carbonising EU economies. As illustrated in Chart 2.1 for 28 OECD countries, new ECB research suggests that economies with a financing structure more geared towards equity than bank credit or other debt have shrunk their carbon footprint by more over the last decades than other economies. This relationship is even more pronounced for private equity, such as venture capital or angel investments. It can be explained by two effects. First, equity markets are better at financing risky innovative companies, which are less rich in tangible assets, and energy-efficient sectors often have a larger share of such companies. By contrast, banks often lend against tangible collateral, which “brown” industries tend to possess to a larger extent than “green” industries. Second, equity investors are more immediately affected by litigation costs, and the lower probability of environmental damage implied by green industries diminishes the likelihood of such costs. A development programme for public and private equity markets could usefully complement ongoing initiatives to promote the issuance of green bonds. While changing the EU financial structure so that it comprises more equity will take time, overall it promises to be more effective in greening the economy than debt-based initiatives. It would also have many other benefits, related to boosting productivity and growth, enhancing private financial risk sharing and strengthening the resilience of financial integration.

Chart 2.1

Financial structure and carbon emissions

(y-axis: percentage change in country-specific carbon emissions per capita between 1990 and 2013; x-axis: total stock market capitalisation divided by the sum of total private credit and total stock market capitalisation, for each country, in 1990)

Sources: Data on carbon emissions (kilotons of CO2 per capita) are from the International Energy Association. Data on private credit and stock market capitalisation are from the World Bank Financial Structure Database.

Notes: “Financial structure in 1990” is defined as total stock market capitalisation divided by the sum of total private credit and total stock market capitalisation multiplied by 100, for each country, in 1990. The points in the chart are for 28 OECD countries.

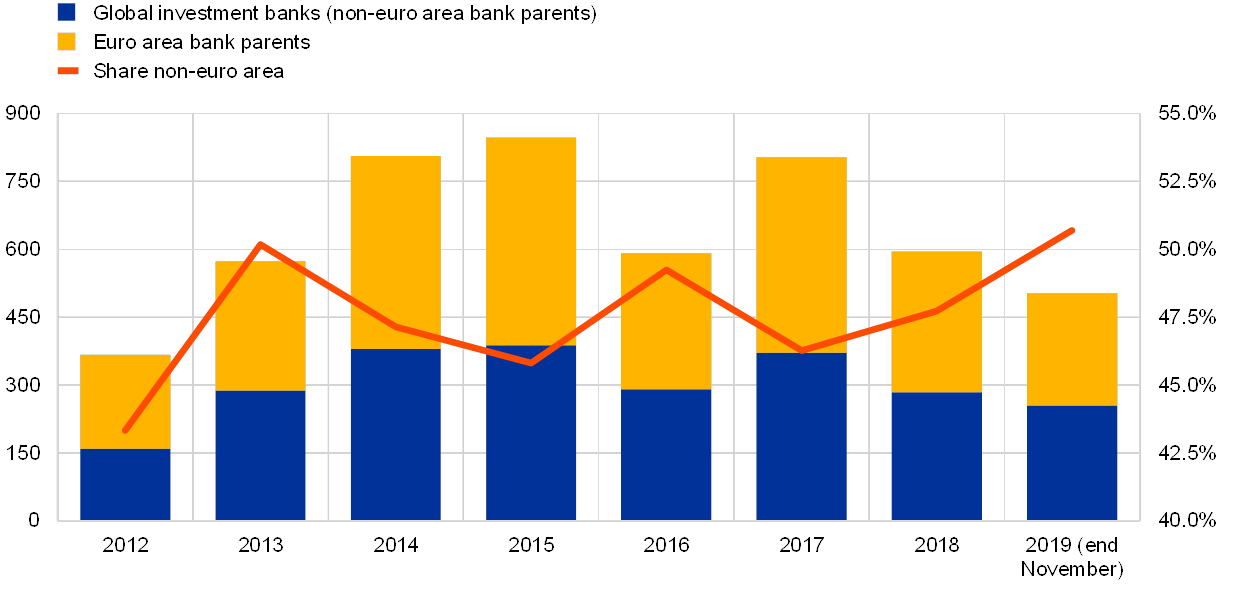

The new economic and financial relationship between the United Kingdom (UK) and the EU27 after Brexit may lead to adjustments in the structure, development and integration of the EU’s financial system and the EU is prepared for all scenarios. Many EU27 companies use financial services currently provided from the City of London. Reliance on the UK is pronounced for capital market-related services, in particular derivatives clearing, various investment banking services such as securities issuance, M&A financing and syndicated lending, as well as securities and derivatives trading. Once the UK leaves the EU Single Market, the cross-border provision of services from the UK will be affected by supervisory and regulatory factors, such as decisions taken under the EU’s equivalence framework. Decisions on equivalence are the competence of the European Commission. Financial stability considerations, including financial stability risks related to the potential divergence of supervisory and regulatory frameworks, will be a key factor in them. The EU is prepared for all scenarios and, in the light of the current uncertainty regarding the future equivalence of the UK’s framework, the private sector must also continue to prepare for all possible developments after December 2020. Where the cross-border provision of services becomes no longer possible, UK-based financial service providers may have to relocate to the EU and/or the EU may have to deepen its domestic capacity, with implications for its financial structure and development.

Apart from regulatory factors, economic incentives for relocations between the UK and the EU27 and other private sector adjustments will depend, among other factors, on economies of scale and scope. For example, economies of scale in the clearing business provide strong incentives for concentration in a single location. Plans of London-based banks submitted to ECB Banking Supervision, as well as other intermediaries’ plans, suggest that some financial groups may relocate different types of activities to a number of Member States. This seems to indicate that “ecosystem” effects may be more important than economies of scope. If confirmed, the trend could enhance the multi-centricity of the euro area/EU27 financial system.

It is important that the new CMU initiatives currently under preparation facilitate the necessary adjustments in the EU financial sector to Brexit. Should the multi-centricity of the EU financial system become more prominent, it will be increasingly important to maintain the fluidity of financial activities between different EU financial centres, avoiding any fragmentation tendencies between them, in line with the integration goal of CMU. The EU should also deepen domestic capacity in the equity space. Euro area NFCs extensively rely for equity issuance on global banks, which largely serve the Single Market from London (see Chart 2.2). For services that will continue to be provided from London, relevant third country frameworks should be sufficiently uniform across EU countries. Regulatory and supervisory coherence is paramount to ensure level playing fields and avoid regulatory arbitrage. Future policy initiatives, notably the envisaged new set of CMU measures, should take such needs to adapt to Brexit into account in a forward-looking manner.

Chart 2.2

Euro area NFCs’ equity issuance via global investment banks

(left-hand scale: number of deals; right-hand scale: percentage shares)

Source: Dealogic.

Notes: Banks involved in deals as manager, co-manager, bookrunner, participant or underwriter are categorised as “euro area” or “global”, depending on the location of the parent. Prior to Brexit, global banks typically accessed the market from London. The bars reflect the number of deals participated in by individual banks. As many banks typically participate in a single deal, this may entail some double-counting of deals on the left-hand scale. The orange line is the ratio between the blue and yellow bars and can be taken as a proxy of the relevance of global banks for the euro area market.

The introduction of an adequately designed common sovereign safe asset could have important benefits for financial stability, integration and development in the euro area. The euro area financial structure currently lacks a common sovereign safe asset. Such a security would develop the financial system by introducing an additional financial instrument with risk/return characteristics that are different from those of existing assets, notably with low risk that is not directly related to a single sovereign. Moreover, such a debt security could be an important ingredient for developing a proper euro area term structure, a key feature of highly developed capital markets based on which many other financial instruments would be priced. Both of these benefits have natural implications for financial integration, not only for the cross-country convergence of asset prices and interest rates, but also for investor diversification beyond domestic assets. But one of the most emphasised effects of a well-designed euro area sovereign safe asset is the potential benefit for financial stability. Notably, significant home biases in banks’ government bond holdings leave important channels of the sovereign-bank nexus still intact, despite major progress with the first two pillars of the banking union. The option to diversify sovereign holdings by also investing in a common safe asset would reduce the scope for direct losses from national fiscal sustainability issues. Furthermore, reducing the relevance of national sovereign benchmark bonds could weaken the link between debt sustainability of the domestic sovereign and bank funding costs (including via high-quality liquid collateral for repurchase agreements). Moreover, as both a common safe asset and changes to the regulatory treatment of banks’ sovereign exposures are part of the European policy debate, indicative simulations in Box 1 of Special Feature B suggest that combining regulatory sovereign concentration charges (i.e. higher capital requirements for banks with more concentrated sovereign debt portfolios) with a safe asset could facilitate the reduction of the home bias, imply a smaller need for reshuffling sovereign holdings above the concentration threshold, and could avoid potential increases in the volatility of banks’ sovereign bond portfolios. While introducing a common safe asset and changing the regulatory treatment of sovereign exposures could be two mutually supporting elements of EMU deepening, discussions on these possible measures should be viewed in the broader context of completing the banking and capital markets unions, which includes the ongoing policy debate on a European deposit insurance scheme.

Such a common sovereign safe asset would also pose multiple challenges, as expressed by some market participants. First, depending on the design, the creation of a common safe asset could have a negative impact on national bond markets. For example, likely the issuance sizes of traditional government bonds could become smaller, which would have a negative impact on their liquidity. Second, in relation to this, the likelihood of finding sufficient buyers in the market for any subordinated debt instruments, which are crucial for the credit quality of any common safe asset, might be low, as the investor base for such products is likely to be smaller than for traditional government bonds. In this regard, specific attention to the proportionate treatment of risks for the common safe asset and the remaining sovereign debt is needed in bank regulation. Third, the sizeable rating dispersion across euro area sovereign debt instruments may complicate the process of creating a common safe asset backed by sovereigns. These points need to be carefully considered.

To reap the intended benefits, a common euro area sovereign safe asset should combine a number of features related to its credit quality, size, incentive effects and alignment with the regulatory and market environment. A common safe asset should have a very high credit quality and be resilient to country-specific as well as more widespread sovereign shocks in the euro area. It should also be designed in such a way that it maintains incentives for sound national fiscal policies. Moreover, the safe asset should be compatible with both regulatory and market standards and meet the collateral eligibility criteria for the ECB’s liquidity operations. Another priority is that the remaining national public debt markets continue to function well. Some asset designs fulfilling these criteria would have the potential to extend the benefit of low sovereign funding costs to a larger set of issuers than is presently the case. The volume of the asset created should also be of a sufficient size, so that the market develops enough liquidity and brings meaningful improvements in financial integration, development and stability. All in all, a well-designed common sovereign safe asset could be a supportive element for the banking and capital markets unions and could therefore contribute to the deepening of EMU. At the same time, the current debate about different safe asset designs illustrates the challenges in fulfilling all the desirable criteria to the same extent.

Structural developments in the euro area financial system

The financial system comprises various agents, financial intermediaries and financial instruments which serve to fulfil the financing requirements of the euro area economy. Such agents include households, non-financial corporations (NFCs) and national governments, while the financial intermediaries include monetary financial institutions (MFIs), Insurance Corporations and Pension Funds (ICPFs), and other financial corporations including non-money market fund investment funds, other financial intermediaries and financial auxiliaries, as well as captive financial institutions and money lenders. The financial instruments include loans, bonds and equities. This section looks at the developments in these elements of the financial system, as well as their integration across the euro area.[11] The main findings emerging from this section can be summarised as follows.

In terms of international comparison, the euro area economy’s financing requirements reached 5.8 times nominal GDP at the end of 2018 – a level similar to the US economy and significantly lower than the Japanese economy. While the requirements are predominantly met through debt and non-marketable financing instruments, their funding also includes a component of financing via listed shares that is significantly smaller than in either the United States or Japan.

The relative weight of different financial intermediaries has changed in recent years. The relative role of MFIs, or more specifically credit institutions, compared to other financial intermediaries has declined since the global financial crisis. Up to the end of 2014 MFIs were still the largest financial sector. Non-credit institutions have gradually been playing a more important role, with the investment funds sector in particular channelling increased amounts of debt and equity financing to the euro area economy. Since 2015 non-money market fund investment funds, financial vehicle corporations and other financial entities together have represented the largest financial sub-sector.

This section begins by analysing the financing of the euro area economy by size and type of instrument, which points to two major developments over the last three years:

- the assets of non-bank financial intermediaries have surpassed in size the euro area banking sector’s assets.[12] This is the result of relatively slower growth in bank assets, further consolidation and concentration in the banking sector, the strong expansion of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet, and increased reliance on market-based intermediation;

- the ratio of financial sector assets to GDP has been contracting at the euro area level since 2015, masking heterogeneity in national developments.

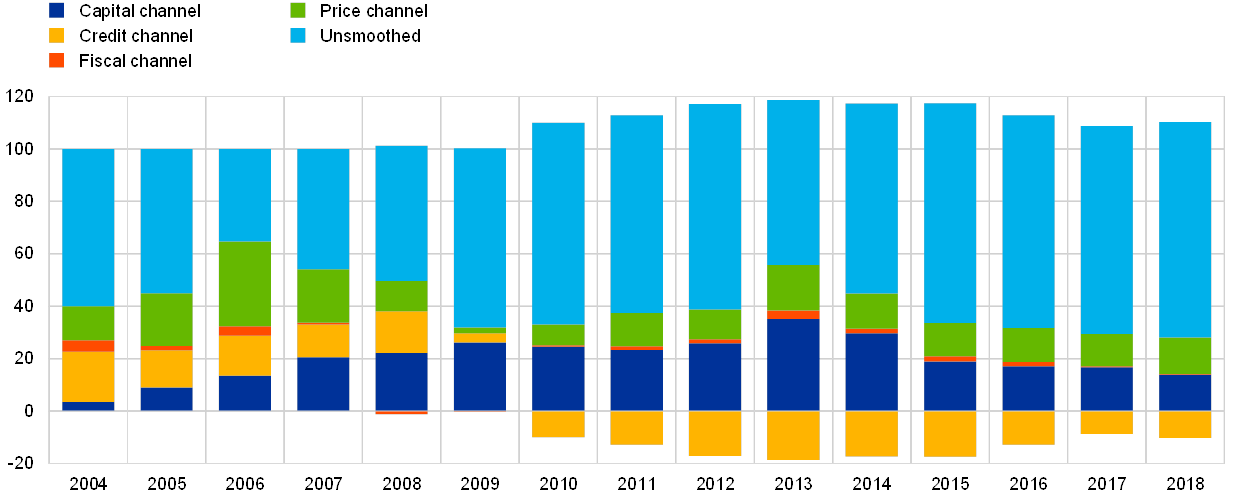

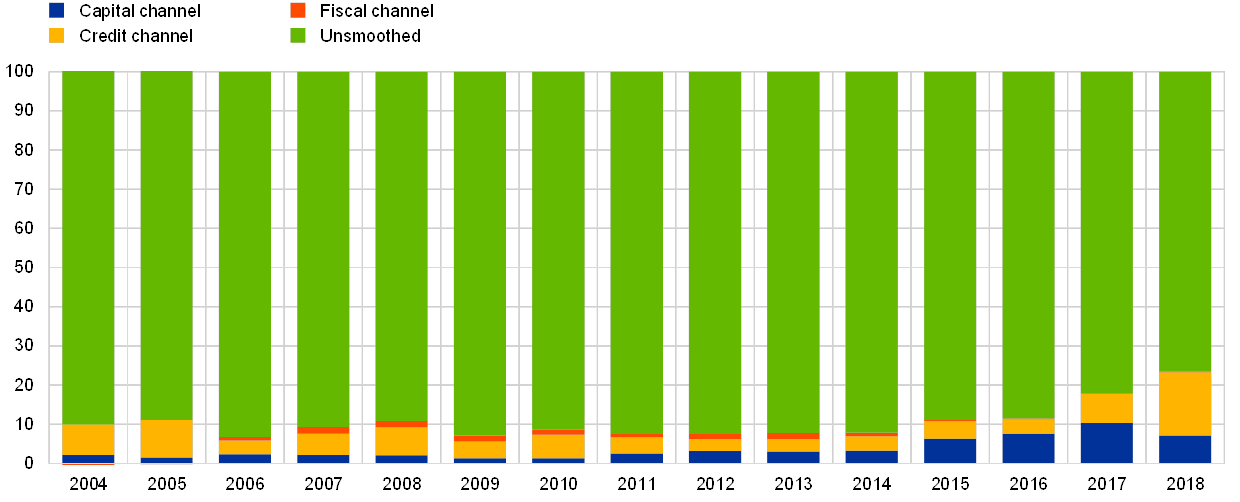

When looking at overall financial integration, both dimensions – i.e. price convergence across the euro area and quantity-based integration via cross-border activities – were hit by the global financial crisis and the subsequent “double dip” in the economy. They have recovered some ground since, thanks to non-standard monetary policy measures (NSMs), reforms of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), and macroeconomic adjustment programmes. Yet this process has stalled in since 2015, while the two dimensions exhibit some discrepancies. On balance, progress in financial integration within the euro area – based on combining a broad range of price-based and quantity-based indicators – has not been very satisfactory in recent years.

Concerning risk sharing, which should reflect both financial integration and resilience, it has risen slightly in recent years, but is modest overall across the various channels in the euro area. Not all risk-sharing channels are operating at their capacity, and some are not even contributing at all due to a reversal of cross-border banking flows. Thus, there may be potential for improved risk sharing through better integrated capital markets.

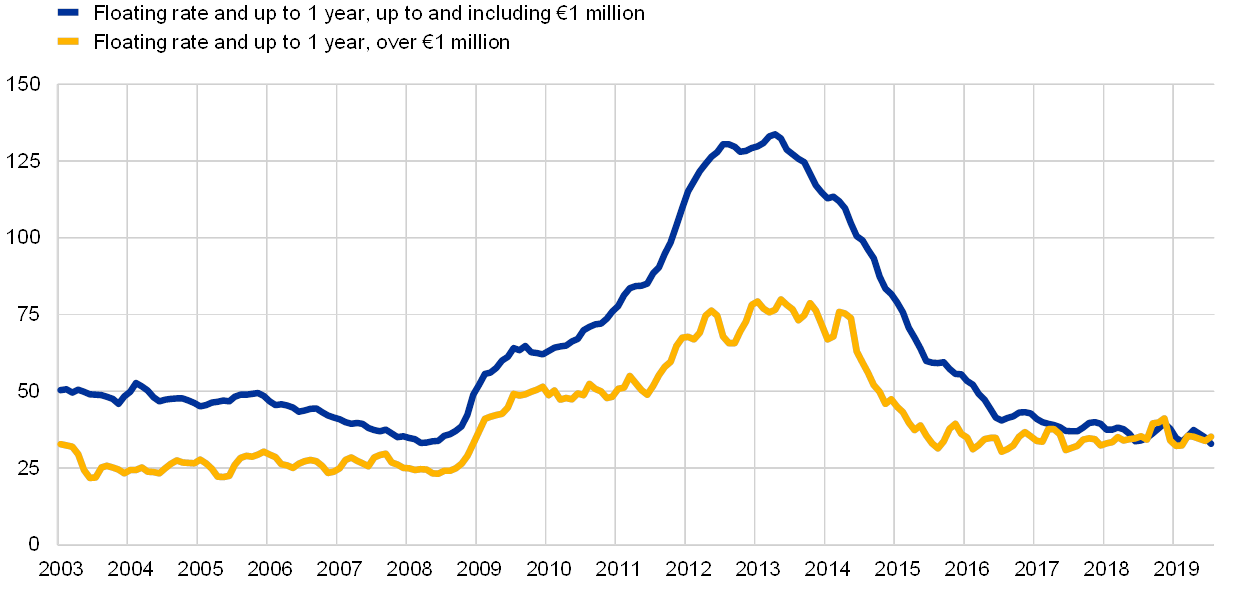

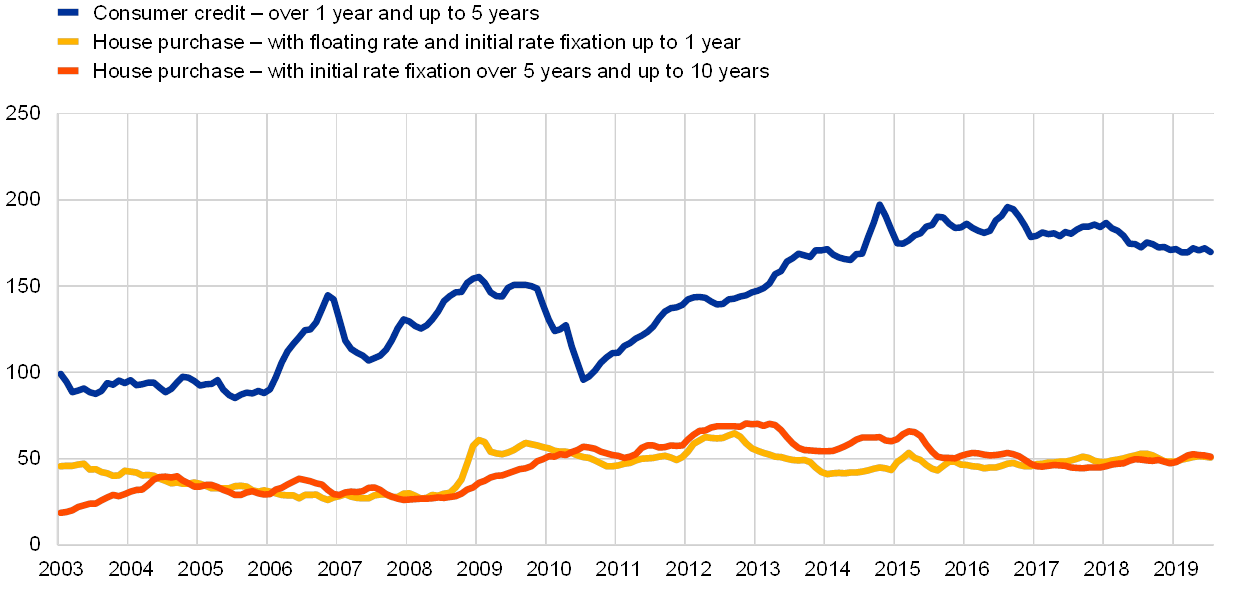

Concerning integration across market segments, a mixed picture emerges. The unsecured and secured segments of the money markets have not responded in quite the same way to an environment characterised by excess liquidity. The integration of retail banking markets is characterised by contrasting developments. Bank retail lending volumes grew across all countries and the share of cross-border intra-euro area loans rose somewhat over the review period. The dispersion of MFI interest on new loans to households is more nuanced. Euro area equity market returns across countries no longer point to a further increase in stock market integration. Meanwhile, cross-border holdings point to a slight increase in fragmentation – also due to political uncertainties in some euro area countries.

This section proceeds by first analysing the euro area financing requirements by size and type of financing instrument (Section 1.1) to understand the demand that the euro area financial sector is expected to meet. Subsequently the section illustrates in more detail how those financing requirements developed over time for the household, NFC and general government sectors (Section 1.2). This analysis provides insights into the evolving liabilities in euro area financial markets. The composition of markets in debt and equity instruments where those seeking and providing financing meet and trade is then presented (Section 2). These markets provide the link to the different types of financial intermediary that channel savings to sectors with borrowing needs. Section 3 reviews structural developments in key sub-groups of these three types of financial intermediaries. The section then turns to the analysis of the recent developments in financial integration (Section 4) by first looking at the price, quantity and quality of integration at the aggregate euro area level (Section 4.1) before looking in more detail at developments in credit markets (Section 4.2) and securities markets (Section 4.3).

1 Liabilities of euro area economic agents

This section characterises the type of instruments used to meet euro area resident economic agents' financing needs and compares them to their equivalents in the United States and Japan. Economic agents incur different types of liabilities depending on the institutional sector[13] they belong to. The aggregate liabilities determine the demand that the euro area financial system should cater for and that is analysed in Section 2.

At the end of 2018, the euro area economy required total financing amounting to EUR 66.6 trillion or 5.8 times nominal GDP (Chart 1 – Section a). Such aggregate financing represented 66% of total[14] (unconsolidated) euro area domestic financial liabilities.[15] Euro area economic agents sourced this financing in the form of debt instruments – loans and trade credits as well as debt securities – and equity instruments – including listed and unlisted shares as well as other types of equity.[16]

The financing of the euro area economy has increased by EUR 1.1 trillion from 2016 to 2018[17]

Chart 1

Financing of the euro area, US and Japanese economies

(ratio to nominal GDP (left-panels); percentages (right-panels); annual data: 1999‑2018)

Sources: ECB for euro area and OECD for United States and Japan.

Notes: The chart is constructed from the liabilities of all economic sectors, excluding liabilities to the rest of the world, loans from NFCs (to net out intra-company loans in this non-consolidated data), currency and deposits, investment fund shares or units, entitlements from pension, insurance and standardised guarantee schemes, financial derivatives and employee stock options as well as other accounts payable. Other equity refers to equity claims that are not securities listed on an exchange and not unlisted securities, such as equity in incorporated partnerships, equity in limited liability companies whose owners are partners, capital invested in cooperative societies or investment by the government in the capital of public corporations whose capital is not divided into shares. Data for the US and Japan are based on the global System of National Accounts (SNA) 2008. The ESA 2010 underlying the euro area data are broadly consistent with the SNA 2008, although in some cases it may be more detailed.

1.1 By type of financial instrument

The financing of the euro area economy is still predominantly debt-based, despite a steady decline in the share of debt securities instruments. The share of debt financing declined from a peak of 73.6% in 2011 to 68.4% in 2018. Nearly 55% of debt financing consists in loans, 38% in debt securities and 7% in trade credits.

General government has issued the largest stock of debt securities outstanding, representing half of the debt securities in the euro area economy. Credit institution liabilities in the form of debt securities represented 6% of total external financing. This share has nearly halved since its peak in 2008 reflecting an advancing but slow process of euro area banking sector consolidation and concentration (see Section 3.1). It also reflects robust deposit growth and notable financing through the Eurosystem, thus reducing the need for debt securities issuance as well as dependency on interbank lending.

Despite gradually increasing from 27% in 2008 to 32% in 2018, equity financing is still well below the 36% share in external financing it had at the start of EMU. Looking ahead, a more significant role of equity financing of the euro area economy would have beneficial implications including diversifying funding sources, increasing financial resilience (see Section 4), and supporting a faster reduction in the carbon footprint of the economy (see Box 1).

Listed shares – a marketable and hence more easily tradable financial instrument – have seen their role in the mix of equity instruments diminish strongly since 1999 as they are increasingly supplanted by unlisted shares (i.e. equity securities not listed on an exchange). The proportion of listed shares has fallen from 46% to 19% whereas that of unlisted shares has increased from 42% to 58%.

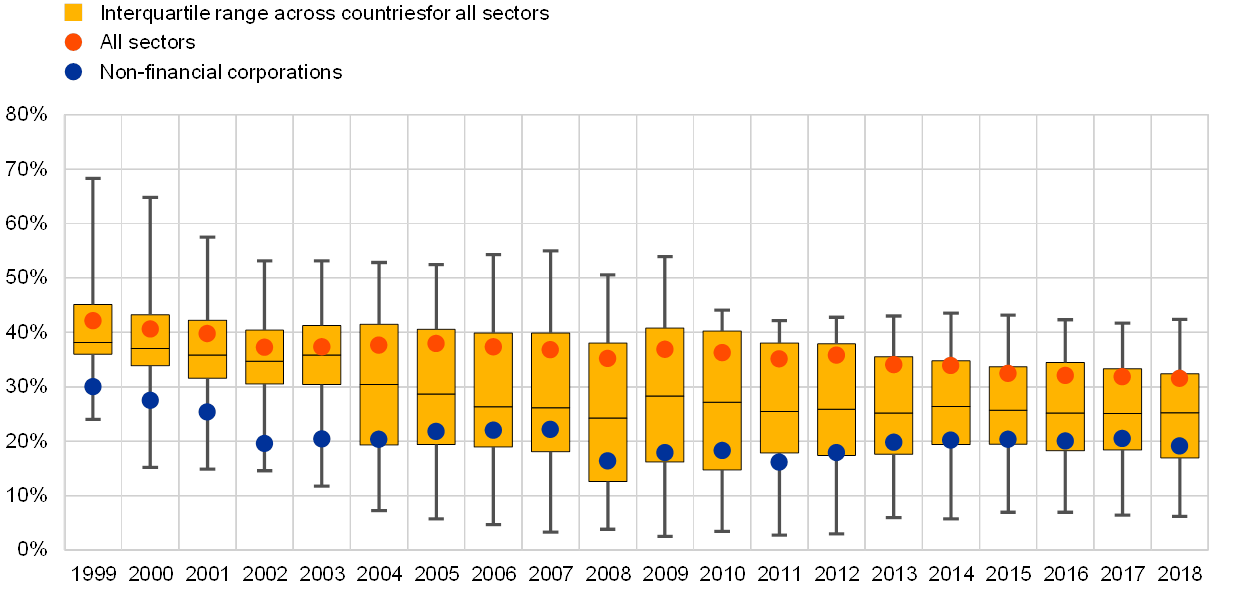

The significant decline in the share of marketable instrument-based financing since the start of EMU has stabilised recently (at 32%). However, this masks significant heterogeneity in developments across Member States (Chart 2). Marketable financial instruments benefit from a broader investor base and – subject to an adequate prudential framework – provide economic agents with a more diverse and resilient funding pool. Therefore, from a financial stability perspective, it is desirable for these instruments to play a larger role in the external financing of euro area Member States. Unfortunately, the share of these instruments remains markedly low, especially the share in the NFC financing mix (19%). Furthermore, we note a downward trend for the overall share of these instruments since 1999, echoing the increasing role of unlisted shares, as indicated in Chart 1. Finally, the downward trend comes with a time-varying distribution across the euro area countries. The current width of the distribution – narrower than during the recent crisis, but broader than at the start of the period – translates into a heterogeneous situation across the various Member States.

The major role of loans in external financing, and the dominance of unlisted shares in equity financing (58%), reflect the high share of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the euro area economy.

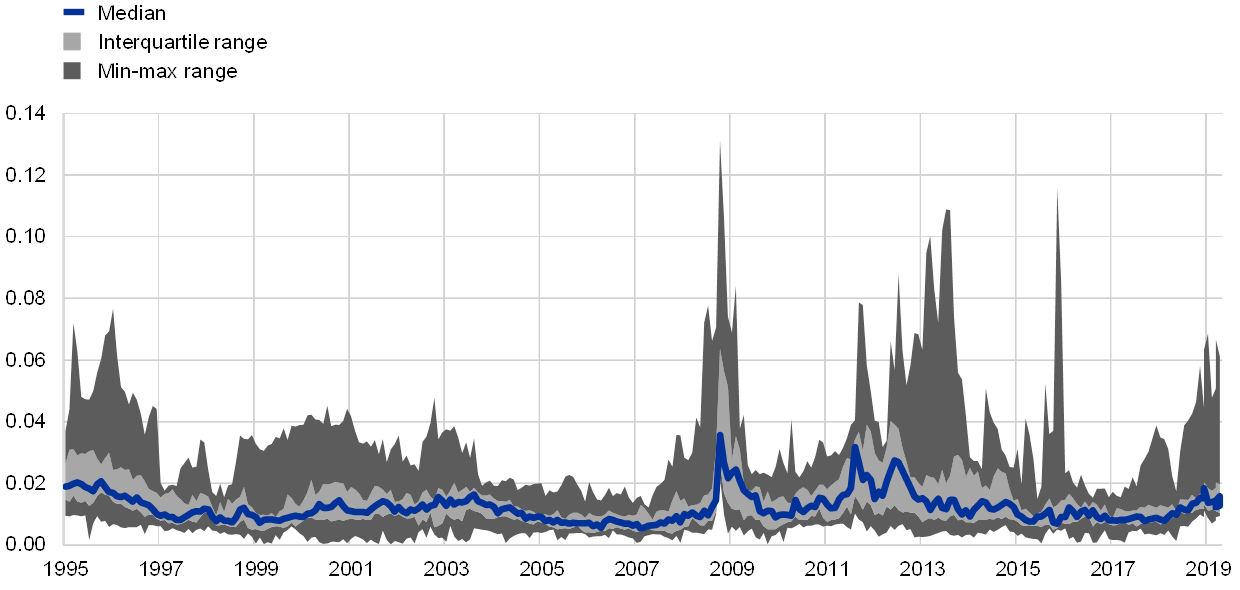

Chart 2

Marketable proportion of external funding among euro area countries

(ratio; annual data: 1999‑2018)

Source: ECB.

Notes: The marketable part of a euro area country’s capital market is defined as the total debt securities and listed shares over total loans (adjusted for intra-company loans), trade credits, debt securities and equity (including listed and unlisted shares as well as other equity). For the years 1999‑2003, the plot is based on only 12 countries (specifically, it excludes Cyprus, Estonia, Malta, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovakia and Slovenia).

A comparison with the financing structures of the US and Japanese economies highlights the following differences:

- At a comparable level in terms of ratio to GDP (5.7), the US economy’s external financing was more equity-based (39%) and marketable instrument-based (52%) (Chart 1 – Section b). It relied less on loans (24%) and featured a larger stock of public sector debt securities (18%). Equity financing was based 51% on listed shares, 8% on unlisted shares and notably 41% on other equity financing instruments.[18] [19]

- While significantly larger in size (7.8 times GDP), Japanese external financing needs featured a stronger debt basis as a consequence of the high public sector indebtedness (Chart 1 – Section c). Moreover, it relied almost equally on marketable financial instruments in general with a significant share of listed share equity financing (16%).

- The marginal role of debt issuances by US and Japanese credit institutions – commonly operating as subsidiaries of larger bank holding companies or financial groups – masks the fact that parent entities – classified as other financial intermediaries (OFIs) – issue debt securities to meet financing requirements and subsequently channel the funding received to the credit institutions via intra-company loans.

Box 1

Does financial structure affect the carbon footprint of the economy? [20]

The recent interest in the ability of green-finance initiatives to fund the decarbonisation of the global economy has laid bare our limited understanding of the link between traditional finance and environmental degradation. Are expanding financial markets detrimental to the environment because they fuel economic growth and the concomitant emission of pollutants, or do they steer economies towards sustainable growth by favouring “green” sectors over “brown” ones? And do credit markets and equity markets have a similar impact on the environment, or does it make economic sense to stimulate one segment of the financial system at the expense of the other in order to contribute to meeting high-level commitments on limiting global warming?[21] These important issues seem to be missing in the current policy discussion about how to de-carbonise advanced economies.[22]

Analysis of data on aggregate carbon emissions and financial structure reveals that the carbon footprint of the economy shrinks faster in economies that receive relatively more of their funding from equity investors than from banks. Chart A illustrates this result: during the quarter-century after 1990, per capita carbon emissions declined more in countries where stock markets were relatively larger in 1990. The statistical relationship between financial structure and carbon emissions is observed while holding the level of economic development, financial development, and environmental regulation constant, and when using policies promoting financial market deregulation and liberalisation as instruments for financial development and improving financial structure. It is also economically meaningful: lifting all countries to a ratio of total stock market capitalisation to the sum of total private credit and total stock market capitalisation of one-half (from a global mean of one-third) would result in an 11.5% reduction in global per capita carbon emissions.[23]

The aggregate effect is explained by two separate mechanisms at the sector level: relatively faster output growth in “green” sectors, and relatively faster declines in emissions per output in carbon-intensive sectors, in countries with deeper equity markets. The former mechanism is similar to one in which financial markets speed up the reallocation of productive resources towards sectors with better growth opportunities.[24] The latter mechanism is related to the ability of financial markets to finance the development and adoption of new technologies which increase within-sector productivity. Unlike most previous research, however, the evidence here suggests that one type of investment (equity) is superior to another (credit) in achieving both goals, i.e. growth in “green” sectors and technological progress in “brown” sectors, at least in the context of the economy’s carbon footprint.

Also strengthening the link between equity markets and green innovation is the fact that deeper stock markets are associated with more green patenting in traditionally carbon-intensive sectors. This is especially the case for patented inventions whose goal is to increase the energy efficiency of the production process. This mechanism is further strengthened when the analysis takes into consideration private equity investments, such as venture capital and angel investments, which are particularly effective in financing early-stage innovation.[25] Importantly, while some of the reduction in domestic carbon emissions is offset by those embedded in the production of imported goods, the “domestic-greening” effect dominates the “carbon-import” effect by a factor of ten.[26]

Firm-level evidence also supports the idea that higher equity investment is associated with faster decarbonisation. In 2006 Belgium introduced a notional interest deduction for corporate equity, in order to reduce the tax advantage of issuing debt. This policy shock provides an arguably exogenous source of variation in the cost of equity financing. Matched data from Orbis and from the European Emissions Trading System suggest that the reform caused Belgian non-financial firms to increase their equity ratio by about 5%, an adjustment similar to that of Belgian banks.[27] Subsequently, these same firms reduced the carbon intensity of their production, also in comparison to similar firms in the same sector in neighbouring countries (such as the Netherlands).

Chart A

Financial structure and carbon emissions

(y-axis: percentage change in country-specific carbon emissions per capita between 1990 and 2013; x-axis: total stock market capitalisation divided by the sum of total private credit and total stock market capitalisation, for each country, in 1990)

Notes: “Financial structure in 1990” is defined as total stock market capitalisation divided by the sum of total private credit and total stock market capitalisation, for each country, in 1990. Data on carbon emissions (kilotons of CO2 per capita) from the International Energy Agency. Data on private credit and stock market capitalisation from the Financial Structure Database.

The superiority of equity financing to debt financing in decarbonising the economy appears to stem largely from equity investors’ propensity to fund intangible projects and their higher aversion to litigation risk. Relative to carbon-intensive sectors, energy-efficient sectors tend to be more innovative and less rich in tangible assets. Innovative, R&D intensive sectors typically grow faster in countries with deeper stock markets. In contrast, sectors rich in tangible assets (which also happen to be more carbon-intensive) expand faster in economies that rely more on bank financing, for example because banks often take less risk and therefore tend to lend against tangible collateral.[28] Second, equity investors see green firms as less likely to suffer environmental disasters, and therefore less likely to be involved in litigation.[29] Thus, the technological “greening” of carbon-intensive sectors as stock markets develop is, to a large degree, explained by equity investors pushing such sectors to develop and adopt greener technologies in an attempt to reduce future litigation costs.

The evidence provided in this box illustrates the challenges implied in limiting the financing of the carbon transition in Europe to bank or debt-based initiatives, and instead suggests a strong emphasis on equity-based initiatives. A number of such initiatives can be embedded in a push to give a stronger equity dimension to the European Capital Markets Union (CMU) project, tapping the European capital markets’ potential to fund innovative, sustainable growth. One specific measure that is crucial in this regard is reducing or eliminating any tax benefits that favour debt over equity. The European Commission has already adopted a proposal on a common corporate tax base which will address the current debt-bias in corporate taxation by introducing an “Allowance for Growth and Investment” that will give companies tax benefits for equity equivalent to those they receive for debt.[30] Other initiatives already on the table that will arguably stimulate equity investment include measures to support the development of venture capital markets, and improving and harmonising insolvency regimes, among others.[31]

In parallel, countries should take measures to counterbalance the tendency of credit markets to finance relatively carbon-intensive sectors and firms. For example, banks can be asked to release information about the environmental performance of the firms they fund. Furthermore, countries can adopt green credit guidelines to encourage banks to improve their environmental performance and to lend more to firms that are part of the low-carbon economy.

Finally, a number of initiatives can be implemented to support the budding market for green bonds, such as improving risk-return profiles, boosting demand, introducing tax incentives, and enabling strategic issuance.[32] Practically non-existent a decade ago, green bonds (i.e. bonds issued by private or public entities and earmarked to be used for climate and environmental projects) have rapidly emerged as a popular way to finance the greening of the economy. Their global issuance stood at $255 bn in 2019, with the EU being the biggest issuer of green bonds in the world ($107 bn), ahead of the United States ($51 bn) and China ($30 bn). While the analysis of their effectiveness is constrained by the short historical window of their existence, recent evidence suggests that green bond issuance does not just improve companies’ value and performance, but also weakly stimulates patented innovation.[33] At the same time, green bonds are typically issued by large listed companies which tend to be much less constrained than smaller companies in their ability to invest in R&D, a fact that puts their usefulness in funding green innovation in question. In contrast, equity investors such as venture capitalists typically fund financially constrained young innovative companies seeking to place a radically new technology in the market. For this reason, measures aimed at stimulating equity investment in Europe are plausibly associated with higher benefits for climate mitigating technologies than measures supporting the market for green bonds.

1.2 By economic sector

The three main euro area economic sectors – households, non-financial corporations (NFCs) and the general government – have distinct funding structures. The following sections examine the evolution of the use of financial instruments by each sector as well as the main funding sources.

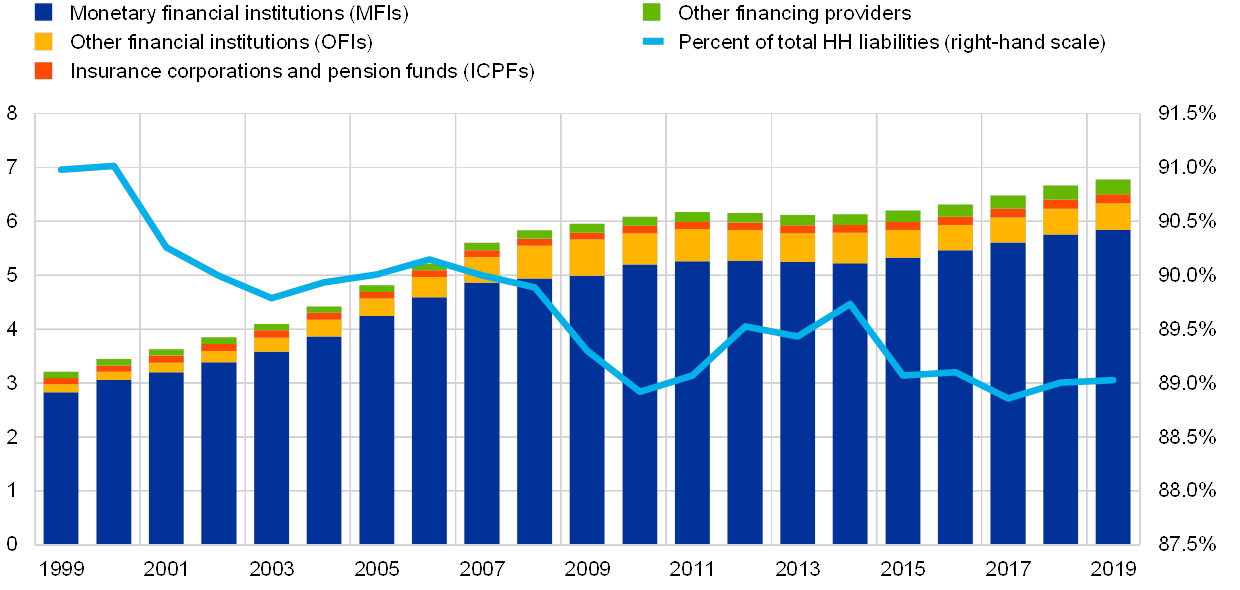

1.2.1 Euro area households

Euro area households finance themselves principally through loans from MFIs, (Chart 3). The presence of the non-banking sector is still limited in this segment of the market. OFI loans consist mainly of securitised loans originated by MFIs. The shares of bank and OFI loans in total loans to euro area households have remained practically unchanged over the past ten years.

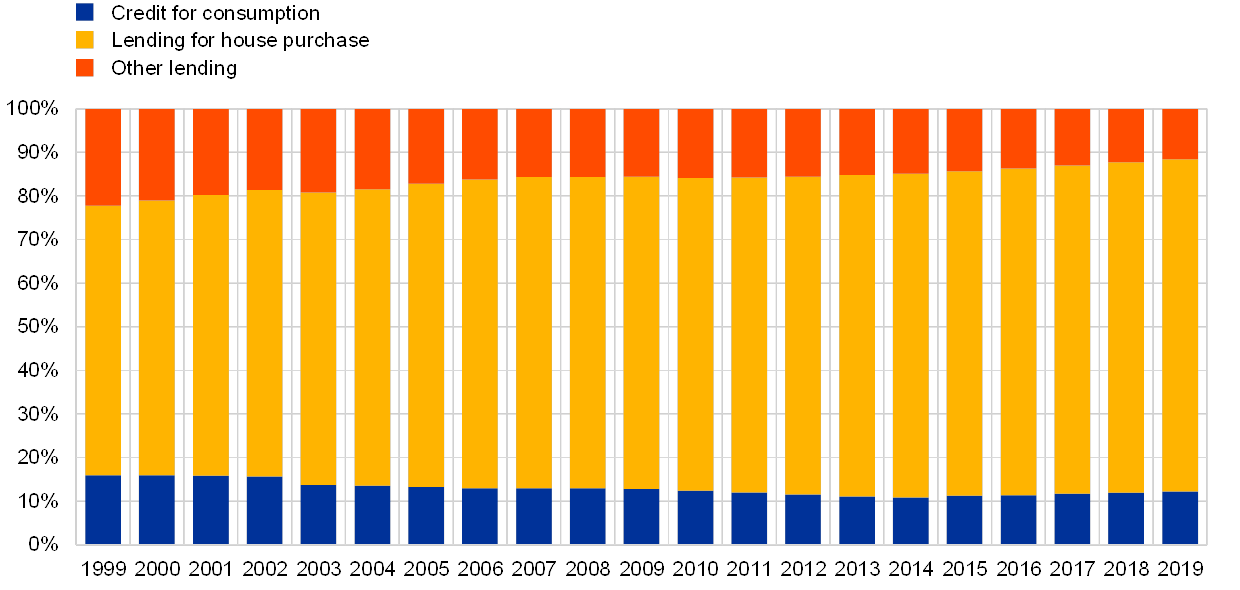

The main reason households have recourse to MFI loans for financing is to purchase houses (75% of MFI loans) with the remaining share being equally distributed between consumer credit and loans for other purposes (Chart 4).

Chart 3

Loans to households and the economic sector providing the financing

(EUR trillions (left-hand scale); percentages (right-hand scale); annual data; 1999‑2019)

Source: ECB.

Notes: OFIs include other financial intermediaries (except insurance corporations and pension funds), financial auxiliaries as well as captive financial institutions and money lenders. OFI loans consist mainly in securitised loans originated by MFIs. 2019 data refer to end Q3 2019 data.

Chart 4

Composition of outstanding MFI loans to households by lending purpose

(percentages; annual data; 1999‑2019)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Loans consist of: (1) loans granted to households in the form of credit for consumption, i.e. loans granted primarily for the purpose of personal use in the consumption of goods and services; (2) lending for house purchase, i.e. credit extended for the purpose of investing in houses for own use or rental, including building and refurbishments; and (3) other, i.e. loans granted for purposes other than consumption and house purchase, such as business, debt consolidation, education, etc. (see Guideline ECB/2014/15).

1.2.2 Euro area NFCs

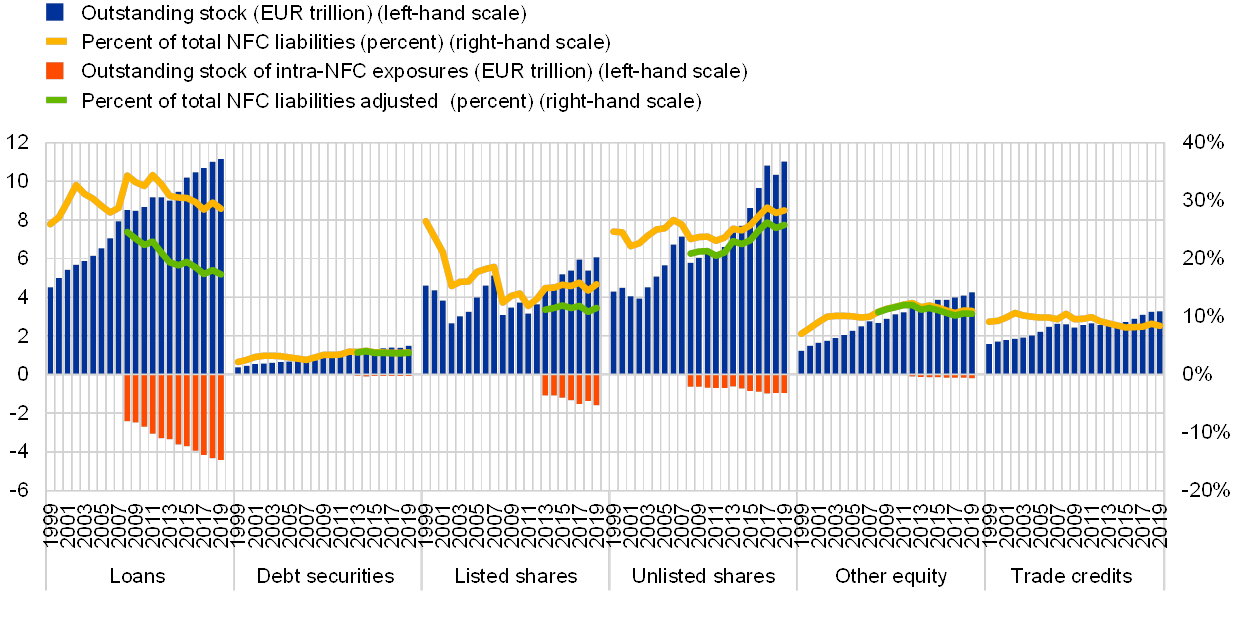

Euro area NFCs have relied principally on loans and unlisted shares for their financing over the last 20 years (Chart 5). These two funding sources currently represent around 60% of NFCs’ total non-consolidated liabilities. The observed low NFC reliance on market-based finance relative to other major international economies is partly due to the larger share of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the euro area.

Equity financing has provided the backbone of euro area NFC financing since 1999. In terms of stocks, equity financing (i.e. listed and unlisted shares and other equity issued by NFCs) represented 53.9% of NFC external financing in 2007, which was 4.5 percentage points higher than in 2003. At that time, this increase was supported by substantial positive valuation effects on the equity issued, reflecting the marked stock price increases, and by the high level of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) witnessed during that boom period. Thereafter, between 2007 and 2011, the share of equity in external financing declined significantly, following the global financial crisis and the euro area crisis as well as the ensuing marked drop in stock prices. Thereafter, it recovered and increased to stand at 55.3% in mid‑2019, mirroring the gradual recovery of the economy and a considerable increase in stock prices.[34]

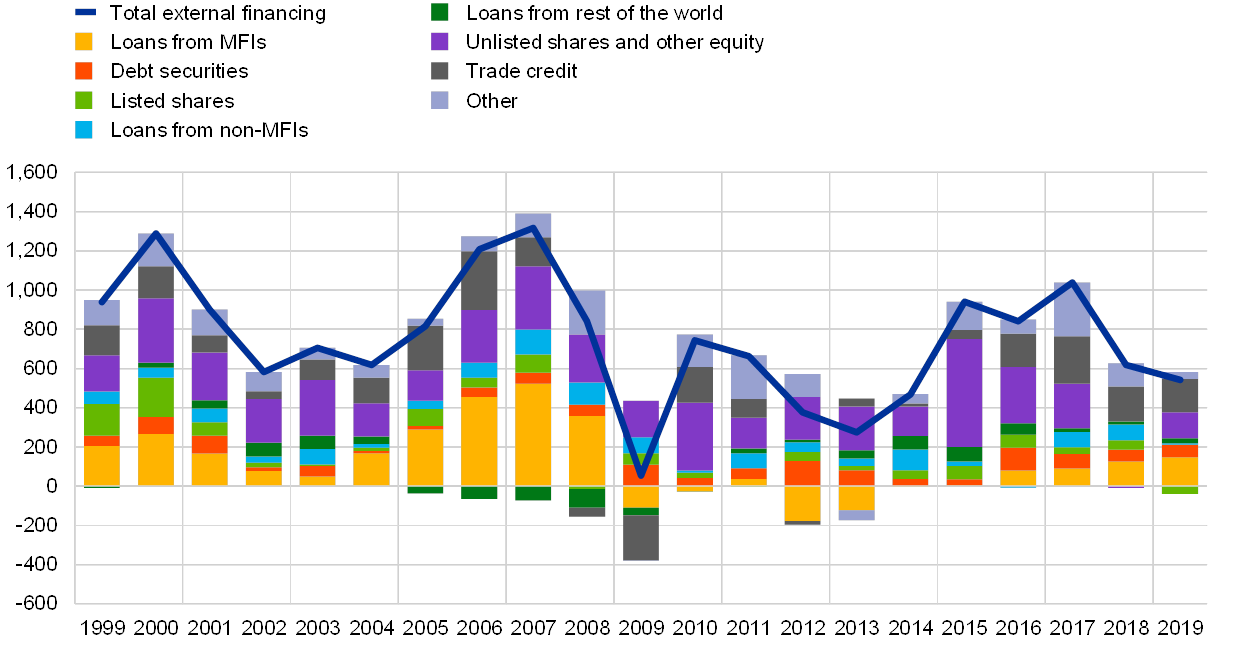

A notable phenomenon is that since 2007 NFCs have gradually diversified their funding structure towards a combination of loan and market-based debt and equity financing (Chart 6). From a stock perspective, bank loans formed 63% of NFC debt financing in 2007, which was 5.7 percentage points higher than in 2003. Borrowing from banks was buttressed over this period by robust economic growth, construction and real estate booms and very favourable bank lending conditions in a number of euro area countries. Post‑2007 the share of bank loans in NFC debt financing has followed a declining trend. In mid‑2019, bank loans accounted for 46.3% of debt financing, while the share of financing through debt securities, loans from OFIs and from the rest of the world increased to 50.5%. Changes in the financing structure of large enterprises drove the decline in the share of bank loans, as these large enterprises increasingly reverted to capital markets for direct debt securities financing and to other financial institutions (OFIs) for indirect debt securities and loan financing. By contrast, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the backbone of the euro area economy, also reduced their reliance on bank credit.

Trade credits have traditionally played an important role in the financing structure of euro area NFCs and now represent close to 10% of euro area NFC liabilities.

Chart 5

Composition of NFC liabilities by type of financial instrument

(EUR trillions (left-hand scale); percentages (right-hand scale); annual data; 1999‑2019)

Sources: ECB and ECB calculations.

Notes: The outstanding stock of intra-NFC exposures is estimated based on financial accounts and balance of payments data. This explains the fact that a significant part of non-investment fund and non-FVC OFI loans are related to debt securities issued indirectly via NFC financing conduits. 2019 data refer to end Q3 2019 data.

Chart 6

External financing of euro area NFCs by instrument

(annual flows; EUR billions; 1999‑2019)

Sources: ECB (euro area accounts) and ECB calculations.

Notes: Non-MFIs include other financial institutions (OFIs) as well as insurance corporations and pension funds (ICPFs). "Other" is the difference between the total and the instruments included in the chart, and includes inter-company loans and the rebalancing between non-financial and financial accounts data. 2019 data refer to end Q3 2019 data.

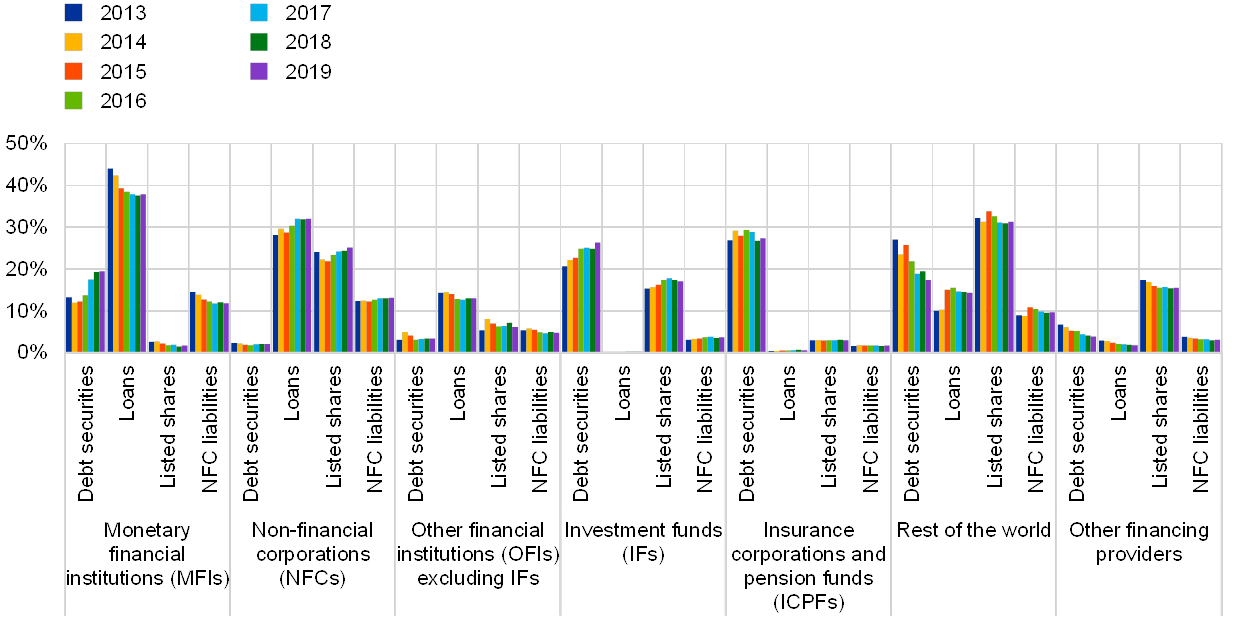

NFCs have sourced their financing from different financial intermediaries or economic sectors. The role of the different financing providers via loans, debt securities and listed shares is characterised as follows (Chart 7):

- Intra-NFC financing is substantial. NFCs rely for approximately 13% of financing on other NFCs. One-quarter of euro area NFC listed shares are owned by other euro area NFCs and 32% of loans are inter-company (often intra-company) loans. The outstanding stock of intra-NFC exposures in Chart 5 provides an estimate for the broader relevance of inter-company exposures.

- MFIs remain an essential provider of debt financing to euro area NFCs. Since 2013 the role of MFIs in the stock of debt financing has declined by 5 percentage points to 36% and the composition of debt financing has shifted towards marketable instruments.

- The ICPF and investment fund (IF) sectors each finance around 27% of NFC debt issuance. IFs moreover provide around 17% of equity financing through listed shares. The ICPF sector has increased its portfolio allocation to IFs over recent years (see Section 3.2.1) and hence also contributes to NFC equity financing indirectly.

- The rest of the world holds close to 10% of NFC liabilities.

This characterisation is incomplete as suppliers of financing in the form of unlisted shares – the biggest component in euro area NFC funding structures – cannot currently be identified due to the limitations of the statistical data. This is an area in which further work is ongoing.

Chart 7

Role of financing-providing sectors in the stock of euro area NFC external financing

(percentages; annual data; 2013‑2019)

Sources: ECB (euro area accounts) and ECB calculations.

Box 2

The need to take the European Capital Markets Union (CMU) further

Well developed and integrated capital markets can make important contributions to economic growth and financial stability, in particular by improving funding access for firms and households and increasing private cross-border financial risk sharing (Section 4). Since the implementation of the CMU Action Plan in 2015 progress has been achieved on the legislative front, albeit to a varying extent across initiatives. While acknowledging that the actual impact on the real economy may take time to materialise, further and timely action is indispensable to drive this project forward.

Benefits of CMU

The Commission has been pursuing the CMU Action Plan in order to unlock more EU and global investment, better connect financing to investment projects, enhance financial stability and deepen financial integration and competition. A deeper and more harmonised CMU complements Europe’s strong reliance on bank financing and strengthens the link between savings and growth.

State of play of CMU