Short-time work schemes and their effects on wages and disposable income

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4/2020.

Short-time work and temporary lay-offs are key instruments for cushioning the economic impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Various euro area countries have implemented or revised their short-time work or temporary lay-off schemes[1] in order to limit households’ loss of income and firms’ wage costs.[2] These schemes also support the economic recovery: they preserve employment relationships so that the workers are available and the firms ready to resume activity once lockdown measures are lifted. There is substantial evidence that these support schemes considerably dampen employment losses in the euro area, compared to countries where such schemes are either scarce (e.g. the United States) or non-existent.[3] Such schemes are designed to bridge temporary shortfalls in activity and demand and need to be balanced with the need for economic restructuring and employment reallocation within and across sectors.

This box estimates take-up rates and calculates wage replacement rates for the schemes in the five largest countries in the euro area. These economies account for more than 80% of the euro area-wide compensation of employees. Combining wage replacement rates with the number of participants makes it possible to calculate the impact of short-time work on household disposable income during the pandemic. Understanding the effects of current and planned short-time work and temporary lay-off schemes is important for developing macroeconomic projections. Therefore the impact of the schemes needs to be monitored as and when more information becomes available regarding actual take-ups.

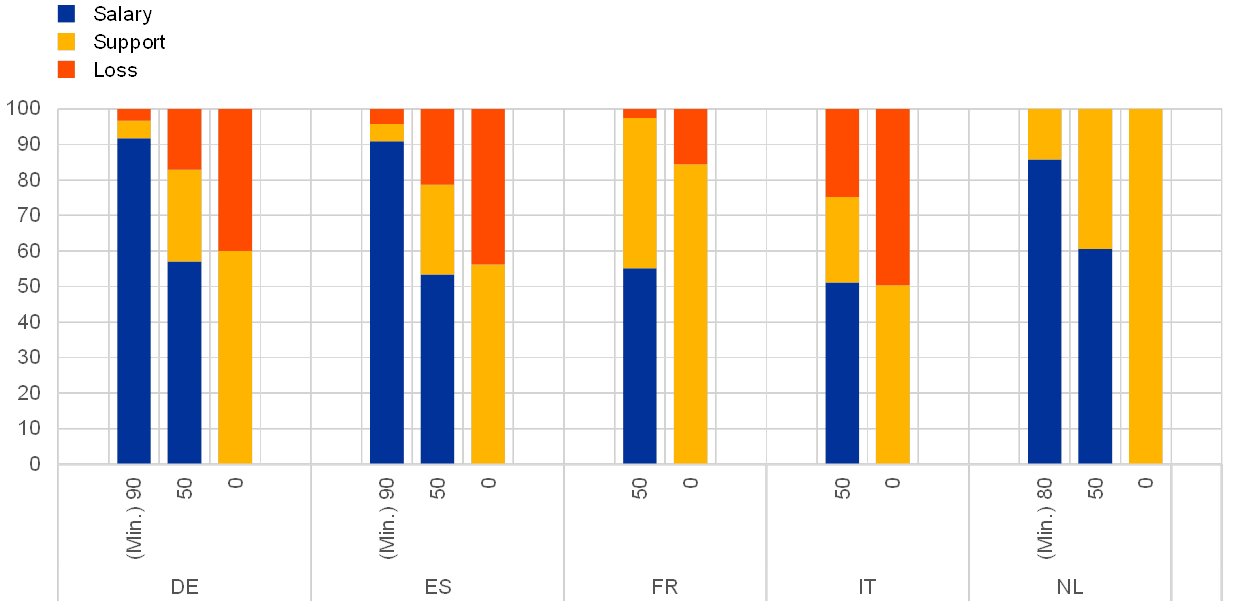

The effects of short-time work schemes on income losses vary according to the reduction in working time. Chart A illustrates that an average employee covered by a short-time work scheme – e.g. in Germany[4], Italy or Spain – is expected to face a loss in net take-home pay of around 25% when working 50% of their regular hours and of around 50% when working zero hours (abstracting from additional sector or firm-specific regulations). The maximum duration of schemes differs substantially across countries.

Chart A

Wage replacement rates for average wage earners

(percentage of net wages and salaries per employee for percentage of regular full-time hours worked)

Sources: ECB staff estimates based on national regulations and input from national central banks.

Notes: The calculations show the net wage income of individual households without children in the first months of receiving the benefit. “Min.” reflects the minimum reduction in working hours required to receive the benefit.

Depending on the design of national schemes, their effects on measures of compensation per employee and on compensation per hour can differ substantially between euro area countries. While in Germany and Spain benefits are paid directly to employees, in the Netherlands, France and Italy employers receive a subsidy to finance their payments to employees. In different countries such schemes may be reflected in statistics in different ways, depending on the classification decided upon by Eurostat. If the benefits are paid directly to employees and recorded as social transfers, while wages and salaries decrease in relation to the number of hours worked, these schemes may show as a strong downward shift in compensation per employee. By contrast, in countries where a scheme is based on a subsidy paid to employers, who continue to pay full salaries for a reduced number of hours worked, the schemes may imply a higher compensation per hour.

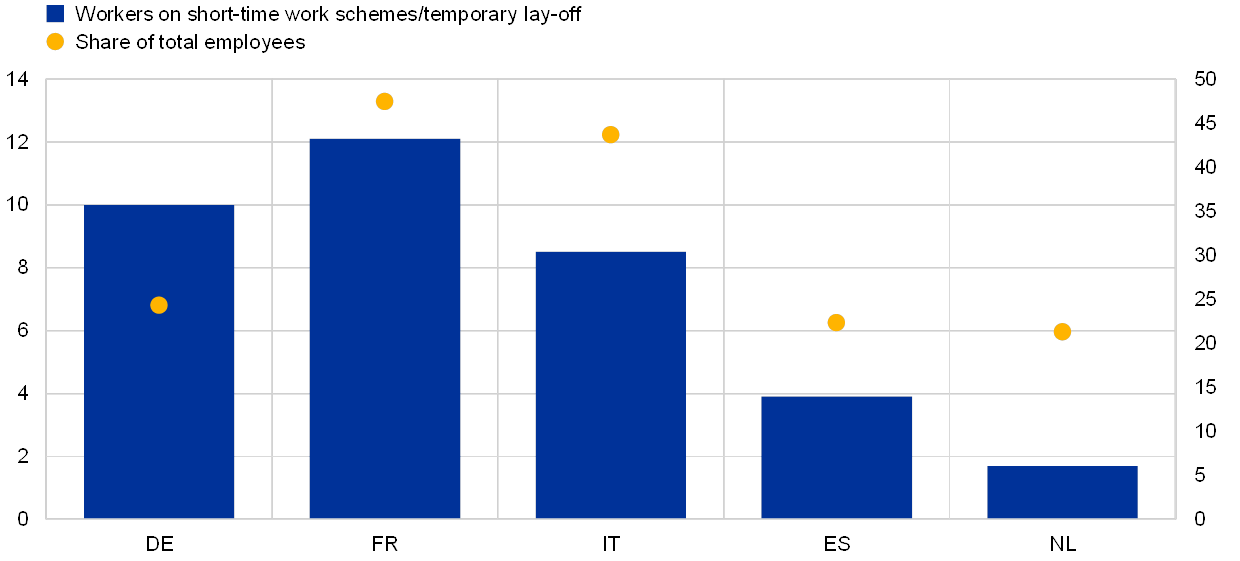

In all five of the largest euro area countries it is likely that a substantial share of employees is on short-time work or temporary lay-off. Preliminary estimates (Chart B) based on different sources suggest there may be about 10 million employees covered by these schemes in Germany (24% of employees) and about 12 million in France (47% of employees). The equivalent numbers are estimated to be 8.5 million in Italy (44% of employees), 3.9 million in Spain (23% of employees) and 1.7 million in the Netherlands (21% of employees). As official data for some of these countries have yet to be released these figures should be viewed with caution. Here they are used for illustrative purposes to gauge the income effects of the measures. Moreover, the figures are likely to be an upper bound, reflecting take-up rates during the time lockdown measures were in place. Additional government measures designed to support the self-employed are not analysed in this box.

Chart B

Estimates of the number of employees on short-time work/temporary lay-off

(left-hand scale: millions of employees; right-hand scale: percentage of employees)

Sources: ECB staff estimates based on information from the IAB (for Germany), Dares (for France), the INPS (for Italy), Factiva (for Spain) and the UWV (for the Netherlands).

Note: Based on data collected up to mid-May 2020.

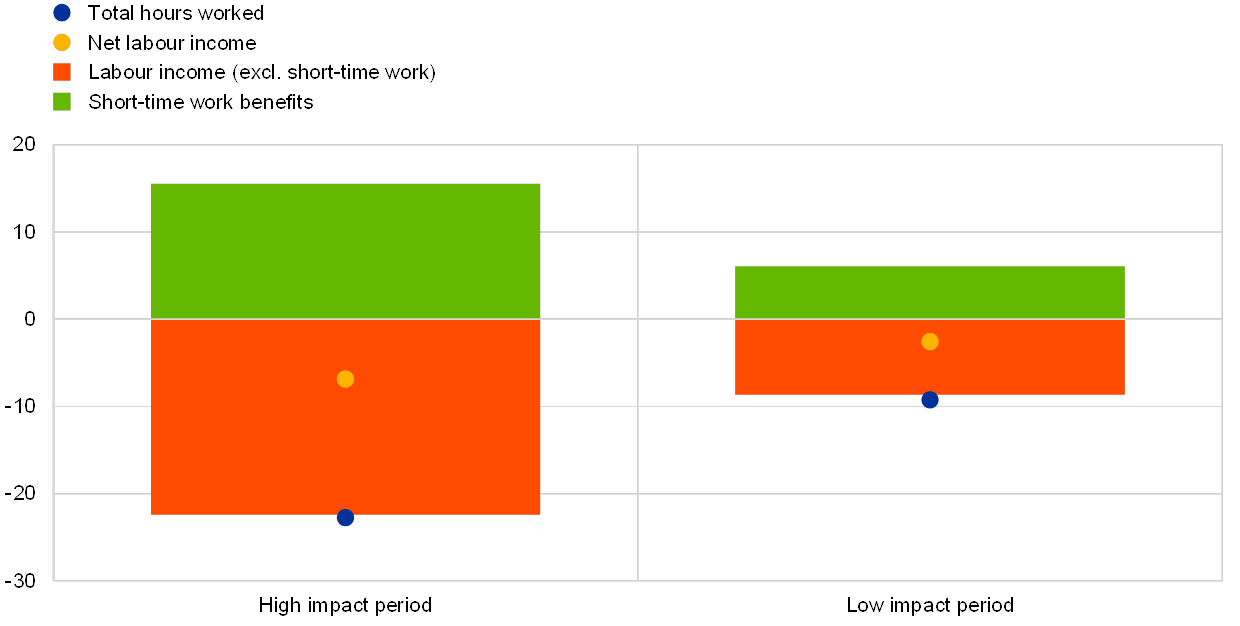

The precise impact of short-time work on households’ disposable income is as yet uncertain. Not only has the number of recipients been changing rapidly, but the precise reduction in the number of hours worked per recipient also remains unknown. To assess the importance of short-time work schemes for households’ disposable income, Chart C presents two illustrations showing a high impact period (applicable during the lockdowns) and a low impact period (with relatively less stringent containment measures applicable after the lockdowns) based on calculations for the five largest euro area countries. Overall, the characteristics of these two periods are in line with the medium scenario for euro area activity in the second quarter of 2020, with strict lockdowns ending in the course of May 2020.[5]

Short-time work benefits are significantly buffering the impact of COVID-19 on households’ disposable income. In the absence of short-time work benefits the drop in euro area households’ labour income from reduced hours worked could amount to -22% during the lockdowns (Chart C, high impact period).[6] However, thanks to short-time work benefits the drop in net labour income should only amount to -7%, although significant differences between individuals and across countries need to be acknowledged. As labour income accounts for about two-thirds of household disposable income, short-time work schemes could be expected to provide a buffer of about 10% of household disposable income (i.e. abstracting from mixed income and property income). After the end of the lockdowns the low impact period illustrates that the loss in net labour income could diminish to -3%, while short-time work benefits rapidly diminish.

As short-time work schemes help to preserve jobs during the crisis, they also mitigate the rise in income uncertainty. Short-time work schemes do not only help households to preserve their income, they also help companies to preserve their cash flow. As a result, fewer jobs should be at risk until the economic recovery arrives. Reducing household income uncertainty is a further channel through which public policy can help to alleviate the adverse effects of the coronavirus pandemic on household spending.

Chart C

Short-time work and labour income in the euro area

(percentage changes, percentage point contributions)

Sources: ECB staff estimates for the (five largest countries of the) euro area based on preliminary information on the number of short-time workers from the IAB (for Germany), Dares (for France), the INPS (for Italy), Factiva (for Spain) and the UWV (for the Netherlands).

Notes: The high impact period uses the estimated number of employees on short-time work in Chart B and assumes a reduction of hours worked by on average 75% per recipient. The low impact period assumes only half of the number of affected employees in the high impact scenario. It assumes a smaller reduction of hours worked per recipient, by on average 60%.

- Changes to existing short-time work schemes have generally been focused on the faster processing of applications, broader eligibility, the compensation of social security contributions, an extension to temporary agency workers, or a change in the duration of the scheme.

- Following the spread of the coronavirus pandemic to Europe, the European Commission also proposed a Council Regulation creating an “instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency” (SURE).

- For a discussion on short-time work during the current crisis see, for example, Giupponi, G. and Landais, C. “Building effective short-time work schemes for the COVID-19 crisis”, VOX-EU, 1 April 2020; or Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva T., Golin M., and Rauh , C. “Inequality in the Impact of the Coronavirus Shock: Evidence from Real Time Surveys”, IZA Discussion Paper Series, No 13183, 2020.

- In Germany, a special regulation is foreseen for 2020: from the fourth month of short-time work onwards, the share of lost income compensated for by the scheme rises to 70% for recipients without children experiencing a loss in working hours of at least 50%.

- See the medium scenario discussed in the box entitled “Alternative scenarios for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic activity in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3, ECB, 2020.

- It is assumed that for each recipient working hours are reduced by 75% on average. This assumed reduction in hours worked is, for example, higher than the actual reduction in hours worked for recipients of short-time work benefits in Germany during the financial crisis. However, it seems reasonable given the substantial reduction in hours worked in several sectors during the lockdown.