- THE ECB BLOG

The dynamics of PEPP reinvestments

13 February 2024

When reading data on reinvestments under the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) one needs to understand how we implement purchases. Director General Market Operations Imène Rahmouni-Rousseau and Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel explain how to avoid pitfalls.

In March 2020, the ECB launched the PEPP “to counter the serious risks to the monetary policy transmission mechanism and the outlook for the euro area” posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Flexibility was a key feature of the PEPP, which allowed us to conduct asset purchases flexibly over time, across asset classes and countries. We ended net purchases under the PEPP in March 2022. From that point, we reinvested the amounts equivalent to maturing assets; and also in this phase flexibility was maintained. However, the ECB has not given details on the actual use of this flexibility, beyond what can be inferred from the bi-monthly publication of data on asset purchases under the PEPP.

If activated, flexible reinvestment leads to positive net purchases in some countries and to negative net purchases in others. However, cumulative net purchases across all countries remain at zero. The Governing Council announced in June 2022 that it would apply flexibility in reinvesting redemptions coming due in the PEPP portfolio, with a view to preserving the functioning of the monetary policy transmission mechanism, a precondition for the ECB to be able to deliver on its price stability mandate. This was briefly covered in our initial review of the PEPP in the ECB Economic Bulletin.

However, positive and negative net purchases across countries can also occur in periods when flexibility is not actively applied. In those cases, it is purely a mechanical consequence of the way reinvestments are implemented. This is due to a “double-smoothing” mechanism designed to ensure market presence in all euro area countries over time, thereby supporting market functioning. This blog post sheds light on these operational implementation aspects in order to dispel misinterpretations of the PEPP purchase data that we publish on our website.

The need to smooth reinvestments

Over a calendar year and under normal market conditions, i.e. when flexibility is not applied, the redemptions of government and agency securities under the PEPP are fully reinvested in the same country in which the principal repayments occur.

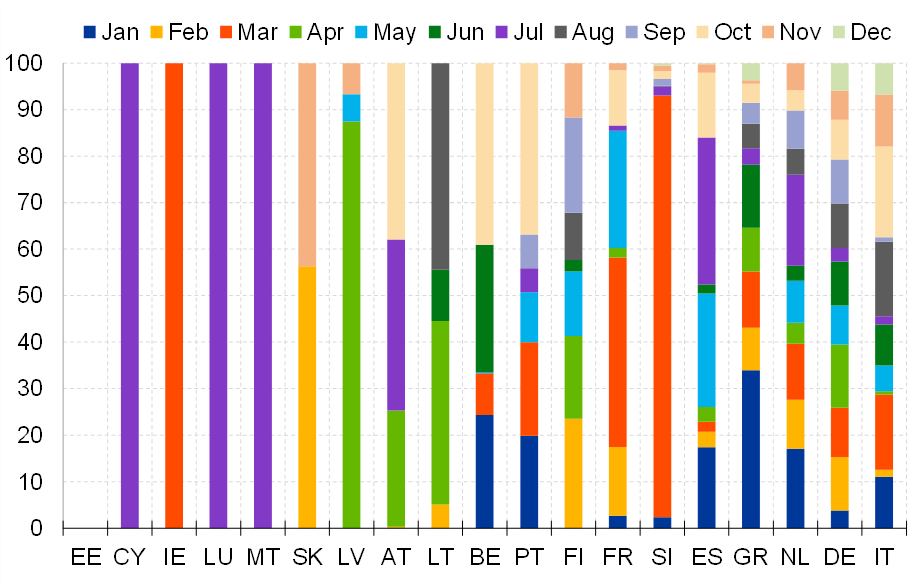

The need for a smoothing of reinvestments by country over a calendar year arises from the fact that redemptions are typically unevenly distributed over time and concentrated in only a few months of the year. A snapshot of the different country redemption patterns is provided in Chart 1. At the one end, in some countries, namely Cyprus, Ireland, Luxembourg and Malta, all redemptions of the year occur in one single month. At the other end, in Germany and Italy, redemptions occur in every month of the year. Most euro area countries fall somewhere in between.

As the Eurosystem conducts purchases across the euro area, it is essential that we factor these country-level redemption patterns into the implementation approach. This allows for a regular and balanced market presence in all countries over the calendar year and preserves the market price formation and market functioning of euro area government bond markets.

Chart 1

Concentration of redemptions per country in 2023 (%)

Source: ECB.

Notes: The chart shows the share of redemptions of each country per month. For example, Ireland has 100% of redemptions occurring in March while Germany has redemptions occurring in all months. Countries are grouped by the number of months with redemptions. For country codes refer to ECB website

Deep dive into the mechanics of “double smoothing”

The smoothing mechanism incorporates two effects. First, the reinvestments per country are smoothed across the calendar year, with the aim of guaranteeing a reinvestment amount in every month. These monthly amounts are calculated so that they add up to the total redemptions of a country within the calendar year. Second, reinvestments are smoothed across countries, meaning that the aggregate redemption amount per month is distributed as reinvestments among the countries. The choice of a calendar year for the smoothing period guarantees a good market presence across countries and is closely aligned with the seasonal pattern of debt management offices, which publish a calendar year schedule for their government bond issuance. By contrast, a simple smoothing, meaning the smoothing of reinvestment solely across time but not across countries, would lead to fluctuations in the total aggregate stock of PEPP holdings over the smoothing period. This would conflict with the monetary policy objective of keeping the holdings of the PEPP portfolio constant during the reinvestment phase.

In mathematical terms, the amount that is reinvested into government and agency securities (abbreviated here as “securities”) of country A in a certain month (in this case April) follows the formula below.

Both total redemptions and the coefficient of reinvestment may change over the year, given the minimum remaining maturity of 70 days for purchases of eligible public sector securities under the PEPP. This means that additional redemptions may appear over the year due to purchases of short-term assets.

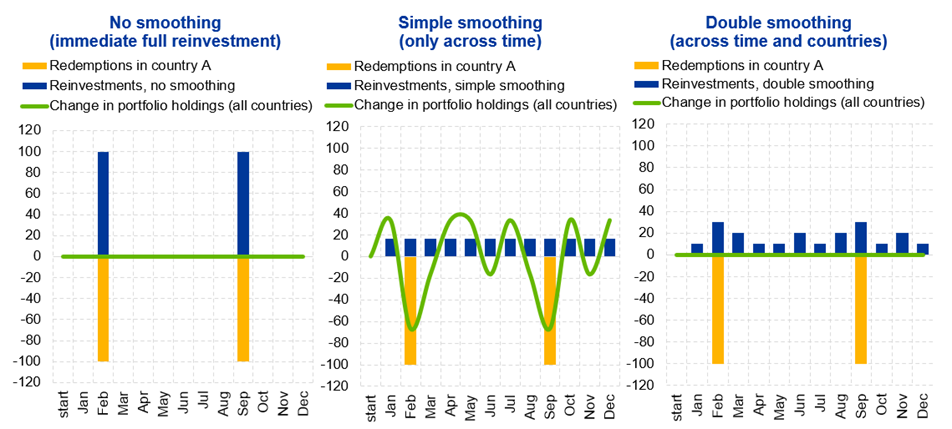

Chart 2 illustrates the effects of simple and double smoothing reinvestment amounts based on a model setup with three countries (A, B and C) and different stylised redemption patterns over a calendar year. The charts focus on country A, with irregular redemptions occurring only in a few months. Meanwhile, countries B and C (not shown) have more regular redemption patterns. Importantly, the green line shows changes in the aggregate portfolio resulting from reinvestments across all three countries. Beginning with the chart on the left, an immediate and full reinvestment of redemptions (i.e. no smoothing) leads to stable aggregate portfolio holdings but comes at the expense of irregular market presence in countries with irregular redemption patterns. The middle chart depicts simple smoothing across time (i.e. months of the calendar year), which distributes reinvestments equally and thereby ensures some market presence in every month. However, this comes at the expense of undesirable fluctuations in aggregate portfolio holdings within a calendar year. Finally, the right chart depicts double smoothing of reinvestments across time and countries, which allows for a regular market presence and no fluctuations in aggregate portfolio holdings within a calendar year.

Chart 2

Stylised example of simple and double smoothing calculations (EUR billions)

Source: Eurosystem.

Notes: The graphs show three methods of conducting reinvestments in a country where redemptions arise in only a few months of the calendar year. The example calculations shown here are based on a portfolio with stylised redemptions in three countries: the country of focus (country A) with irregular redemptions of EUR 100 bn in February and September, country B (not shown) with regularly occuring redemptions of EUR 50 bn per month, and country C (not shown) with redemptions of EUR 50 bn in March, June, August and November. While the charts focus on country A, the change in portfolio holdings, shown in green, arises from the dynamics across all three countries. The underlying data for these charts is available upon request.

How to read 2023 data on PEPP purchases

A crucial consequence from the mechanics explained above is that the double-smoothing mechanism leads to fluctuations of the monthly net purchase amounts within a calendar year. However, it does not change in any way the cumulative net purchases at the country or aggregate level for the full calendar year, which add up to zero unless PEPP flexibility is applied.

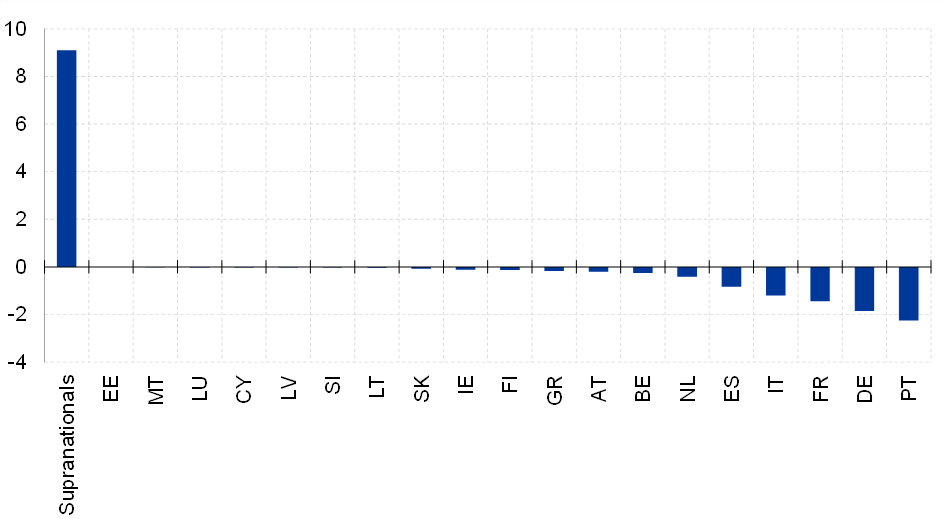

One caveat to this observation in 2023 is that the Eurosystem increased its reinvestments in supranational bonds by an average of €1 billion per month, by reducing reinvestments in government and agency securities accordingly. This was an operational decision implemented as of March 2023, with the aim of achieving a gradual catch-up in supranational bonds to the 10% target share of cumulative net purchases of public sector securities. As such, it aimed to fulfil a legal requirement of the PEPP decision.[2] Each country with redemptions in 2023 has contributed to this gradual reallocation of reinvestments according to its capital key. This explains the overall decline of cumulative net purchases per country at the end of 2023 when compared with the observed levels at the end of 2022 (Chart 3).[3]

Chart 3

Cumulative net purchases for 2023 (EUR billions)

Source: ECB. Notes: For country codes refer to ECB website.

Another element to take into consideration when interpreting the published data is that the smoothing of reinvestments is conducted over a calendar year, while the purchase data of PEPP at country level are published every two months (after the end of January, March, etc.). The full calendar year can hence not be reconstructed from the published bi-monthly data. However, this blog post provides additional 2023 calendar year data, allowing for a cross-check of the neutrality of the smoothing mechanism over the calendar year.

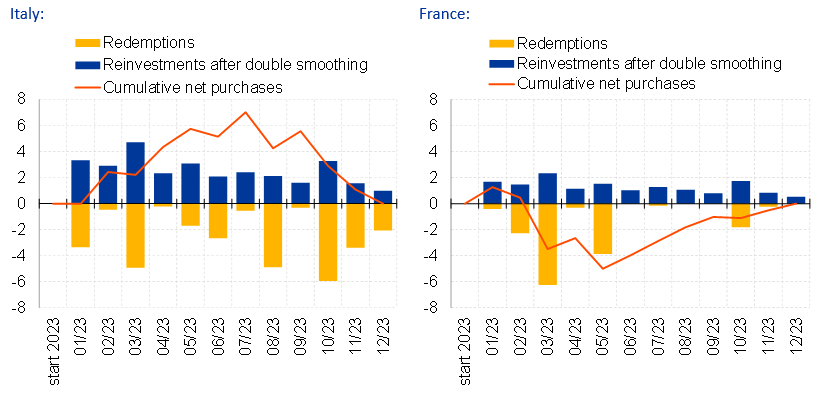

Finally, the different profiles of redemptions over the calendar year matter for the distribution of reinvestments after smoothing and consequently also for the fluctuation in net purchases across countries. For instance, in some countries (such as Italy) redemptions occurred every month in 2023, while in others (such as France) they were less regular. In practice, the smoothing aims to offset the impact of different patterns of redemptions in order to guarantee a more regular market presence of the Eurosystem over the year. It leads to differences in timing between redemptions and reinvestments, and consequently to positive net purchases (when reinvestments are higher than redemptions) and negative net purchases (when reinvestments are lower than redemptions) at different times during the calendar year.

Country-level purchase data for Italy and France show how the smoothing mechanism works in practice. In Italy, where a large amount of redemptions occurred later in the year, the smoothing mechanism brought forward reinvestments to the beginning of the year. This leads to positive net purchases in the early months (Chart 4, Italy). Meanwhile, a different picture emerges in France, where the smoothing mechanism shifts the relatively larger amount of redemptions early in the year to reinvestments later in the year. This leads to negative net purchases from March onwards (Chart 4, France). Importantly however, the fluctuations in net purchases are temporary and – abstracting from the reallocation to supranational bonds – cumulatively add up to zero towards the end of the smoothing period, i.e. at the end of the calendar year.

Chart 4

Redemptions, reinvestments and cumulative net purchases (EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Note: Chart shows reinvestment amounts before reallocation to the catch-up in supranational bonds.

This smoothing mechanism will remain in place under the PEPP until reinvestments are discontinued. Towards the end of 2024, the cumulative net purchases per country should decline across all countries, given the Governing Council’s decision[4] to reduce PEPP reinvestments by €7.5 billion on average per month over the second half of the year.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this blog post has explained why no inferences about the use of flexibility under the PEPP can be drawn from simply considering cumulative net purchases in different countries. Interpreting PEPP purchase data requires a thorough understanding of the double-smoothing mechanism, which ensures regular market presence across euro area countries over time, thereby preserving price formation and supporting market functioning.

We are grateful to Anna Aleksina, Eduard Betz and Joaquim Gomes for their contributions to this blog post.

In line with Article 1(2)(a) of Decision ECB/2020/17 on PEPP, the allocation of portfolios for the public sector securities follow the Decision ECB/2020/9 recast on PSPP, whereby the book value of net purchases, i.e. cumulative net purchases, should be allocated as follows: 10% in marketable debt securities issued by eligible international organisations and multilateral development banks, i.e. to supranational bonds, and 90% in marketable debt securities issued by eligible central, regional or local governments and recognised agencies. As mentioned in “The pandemic emergency purchase programme – an initial review”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2022, during net asset purchases the allocation to supranational bonds was below 10%, as conducting 10% of purchases under the prevailing liquidity conditions for those securities could have risked distorting that market segment. As the liquidity in that market segment has recently developed benignly, the Eurosystem could proceed with the catch-up towards 10% to fulfil the legal guidelines.

The decrease in cumulative net purchases in Portugal is the result of specific market liquidity conditions and reflects the overall attempt of the Eurosystem to avoid distortions to price formation through its purchases.

ECB (2023), “Monetary policy decisions”, press release, 14 December.

-

13 February 2024