A preliminary assessment of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the euro area labour market

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5/2020.

This box analyses labour market developments in the euro area since the onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The containment measures implemented from mid-March resulted in a sharp fall in euro area real GDP in the first quarter of 2020.[1] Business and consumer survey data indicate that the fall deepened in April and May. However, employment and unemployment do not appear to have been significantly affected. In this regard, the reaction of the euro area labour market to the COVID-19 pandemic appears in sharp contrast with that observed in the United States, where unemployment increased rapidly. This box examines the discrepancy between business and consumer survey indicators and the main headline labour market indicators for the euro area. In addition, we discuss the possible effects of lockdown measures on unemployment statistics in view of the internationally agreed definition of unemployment, and elaborate on the adjustment of hours worked and on the widespread use of short-time work schemes and temporary lay-offs, which are the key policies that have supported the euro area labour market since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

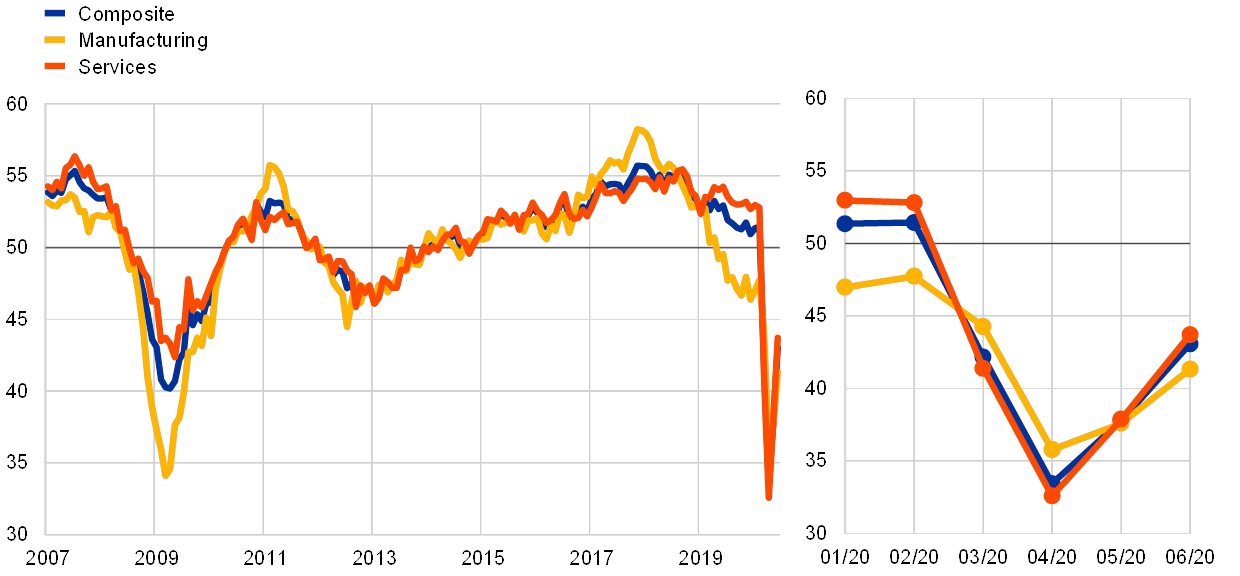

Monthly surveys on employment perceptions and expectations point to a strong deterioration in the euro area labour market. The PMI indicator of employment perceptions declined from levels of 51.4 in February 2020 to an historic low of 33.4 in April, rebounding to 43.1 in June as a consequence of the loosening in the containment measures during this period (see Chart A). The decline was particularly acute in the services sector, with the accommodation, food and beverage services and the warehousing and transportation sector being most affected. As for the manufacturing sector, the decline was also broad-based across sectors, and most prominent for motor vehicles, fabricated metal products, and machinery and equipment sectors. Overall, such large declines in these surveys point to a strong contraction in employment in the second quarter of 2020.[2]

Chart A

PMI Employment

(diffusion index)

Source: Markit.

Notes: A level below 50 indicates a contraction in employment. The latest observation is for June 2020.

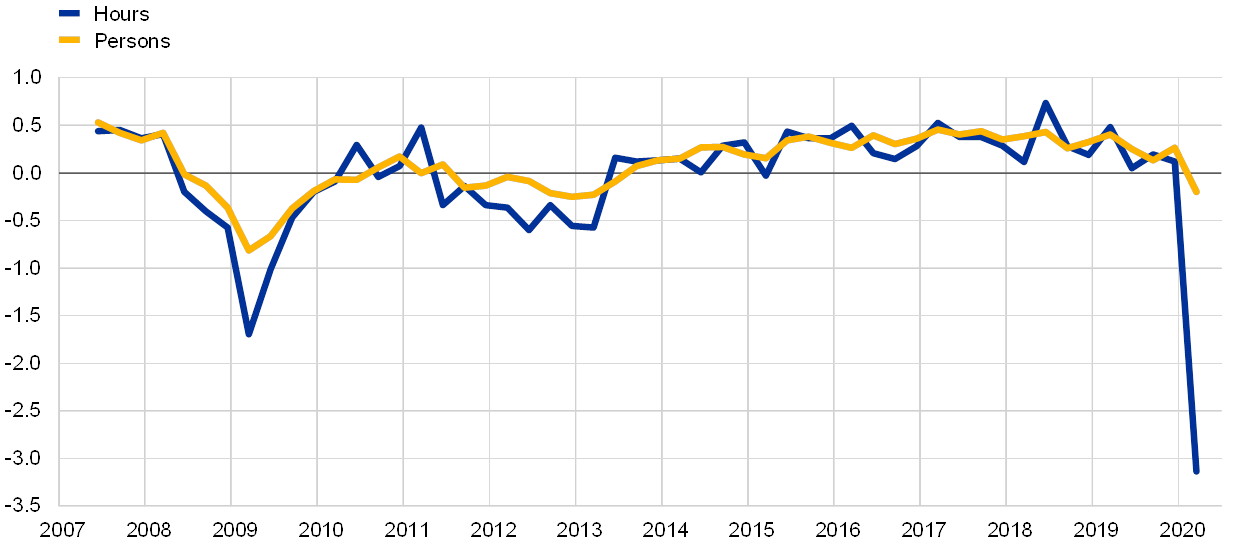

There was a historic decline in the number of hours worked in the first quarter of 2020, which helped put into context the muted response of employment. Although containment measures in the majority of euro area countries only started in mid-March, total hours worked, as recorded in the national accounts, dropped quarter on quarter by 3.1% in the first quarter of 2020, in line with the observed 3.6% decline in real GDP in the same quarter. The decline in hours worked was almost twice as large as that recorded in the first quarter of 2009. The decline in hours worked in the first quarter of 2020 was mostly driven by an adjustment in the intensive margin of labour, i.e. the average number of hours worked per person employed. In the first quarter of 2020, average hours worked decreased quarter on quarter by 2.9%, while the decline in employment remained relatively muted in the changing economic environment at 0.2% (see Chart B). The relative contributions of average hours worked (around 90%) and employment (around 10%) to the decline in total hours worked contrast with those observed in the first quarter of 2009, where both margins accounted for roughly half of the decline of total hours worked.

Chart B

Employment growth

(quarter-on-quarter percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Note: The latest observation is for the first quarter of 2020.

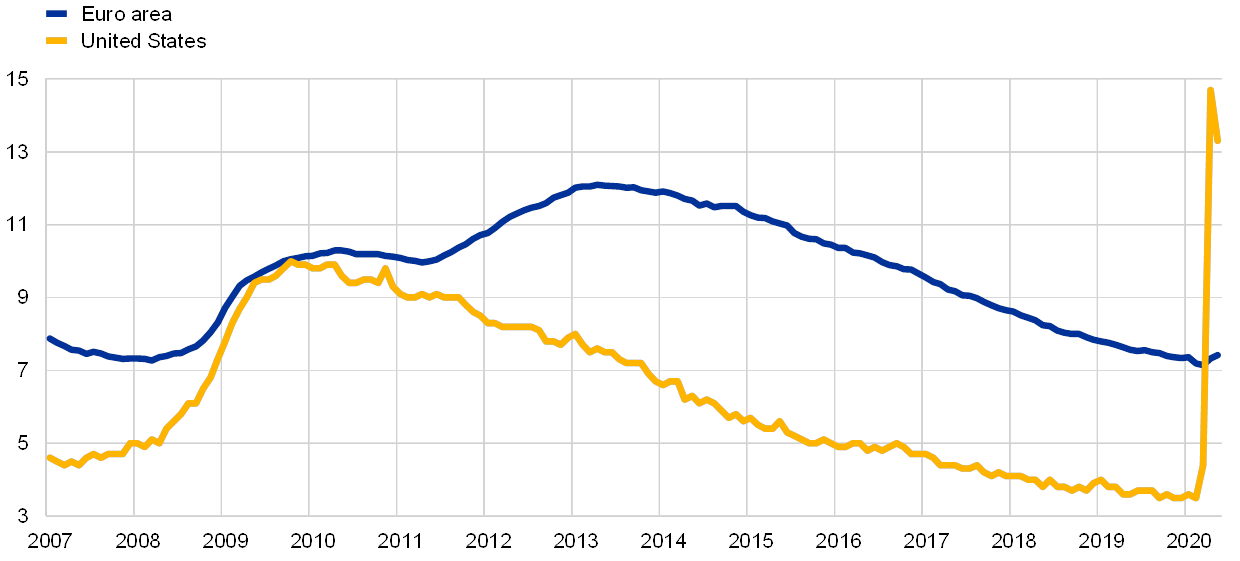

The moderate increase in the unemployment rate up to the end of May is in sharp contrast with indicators of economic activity. The increase in the unemployment rate until the end of May was lower than what could have been expected based on its historical relationship with GDP (see Chart C). In the United States, between January 2020 and May 2020, the number of non-farm payroll employees decreased by 19.5 million and the unemployment rate increased by 9.8 percentage points.[3] By contrast, the muted responses of employment and unemployment during the COVID-19 crisis in the euro area compared with the labour market dynamics observed for the United States have been a noticeable feature of the euro area labour market.[4] The reclassification of some people from unemployment into inactivity could be affecting the unemployment statistics. According to the International Labour Organization’s definition of unemployment, persons losing their jobs or being previously unemployed should be classified as being outside the labour force if they are not actively searching for a job or are not available to take up employment at short notice. This feature would lead to a muted response in terms of the rise in unemployment resulting from the COVID-19 containment measures.[5] Another key difference is that, in the United States, temporarily laid off workers are considered unemployed, whereas in the euro area the persons affected by short-time work schemes or temporary lay-offs remain, in most cases, on the firms’ payroll and are thus not considered unemployed.

Chart C

Unemployment rate in the euro area and in the United States

(percentages of the labour force)

Sources: Eurostat and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note: The latest observation is for May 2020.

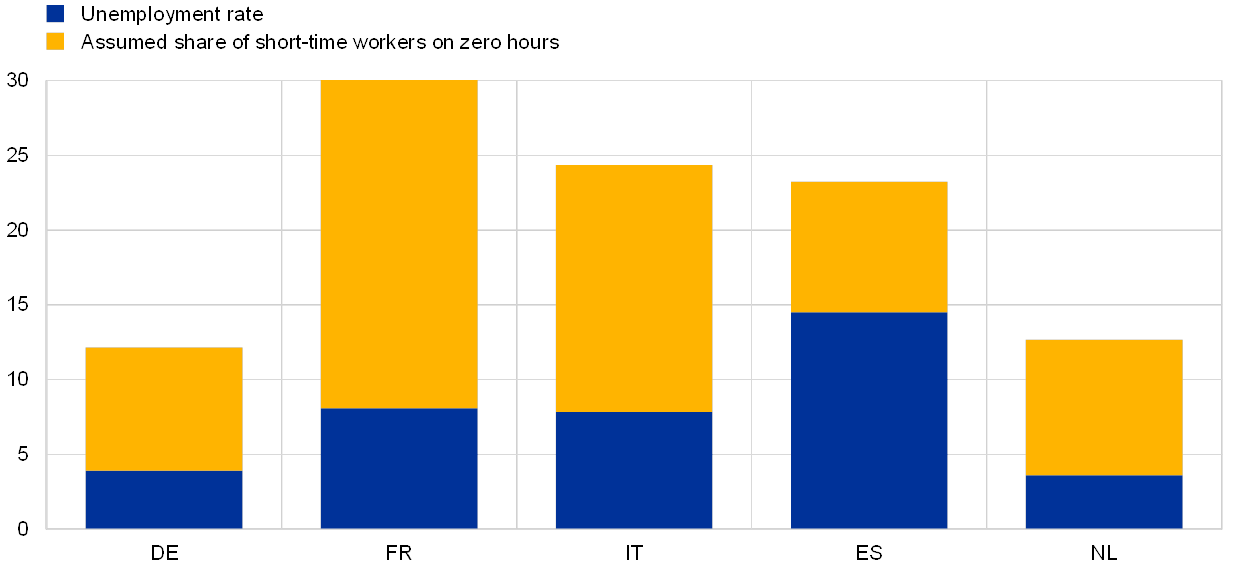

The widespread use of short-time work schemes in the euro area is one of the key factors behind the overall muted immediate response of the labour market to the COVID-19 crisis. The national governments of euro area countries have implemented extensive labour market policies designed to support workers’ incomes and to protect firms’ jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, short-time work schemes and temporary lay-offs have been put in place across the euro area countries, successfully containing dismissals, supporting incomes and helping firms to effectively reduce their payroll costs.[6] Given the sudden contraction in firms’ sales during the COVID-19 crisis, these schemes have played an important role in helping firms’ to reduce their liquidity needs, while allowing them to resume activity more swiftly after the lockdown by keeping the worker-job relationship intact during the lockdown. The number of workers in short-time work schemes is unprecedented across euro area countries.[7] Preliminary estimates of the number of workers affected based on firms’ applications to join these schemes show that a substantial share of employees have been affected. These could amount to a maximum of 10.6 million employees in Germany (26% of the total number of employees in the country), 12 million employees in France (47% of employees), 8.1 million in Italy (42% of employees), 3.9 million in Spain (23% of employees) and 1.7 million in the Netherlands (21% of employees).[8] Indeed, if one takes into account the number of workers in short-time work schemes and on temporary lay-offs, the unemployment rate in the euro area would have reached much higher levels than those currently observed. Chart D provides an illustrative example by adding to the unemployment rate half of the workers in short-time work schemes, assuming that they worked zero hours during May.

Chart D

Unemployment rate and short-time workers in May 2020 for the five largest countries in the euro area

(percentages of the labour force)

Sources: ECB staff estimates based on information from the IAB (for Germany), DARES (for France), the INPS (for Italy), Dow Jones Factiva (for Spain) and the UWV (for the Netherlands).

Notes: Based on data collected up to 8 July 2020. For illustrative purposes, the unemployment rate is augmented with the number of workers affected by short-time work schemes and working on zero hours, which is assumed to be half of the workers in short-time work schemes (based on the number of firms’ applications). For comparable calculations, see the box entitled “Short-time work schemes and their effects on wages and disposable income”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, 2020.

The success of the widespread use of short-time work schemes in supporting the euro area labour market will depend critically on the dynamics and duration of the crisis. Labour market policies, in particular short-time work schemes and temporary lay-offs, are supporting employment and mitigating the increase in the unemployment rate in the euro area. These measures can support a faster recovery of the labour market, as they allow firms and workers to resume activity without the costly and lengthy process of search and matching that would have to occur once the employment relationship was lost. This is even more important, as the crisis is more likely to affect low-skilled workers, which usually have higher unemployment rates. Nonetheless, it is to be expected that not all workers in short-time work schemes and on temporary lay-offs will be able to return to their previous jobs.[9] As a consequence, a further increase in unemployment in the euro area is expected in the short term.

- See the box entitled “Alternative scenarios for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic activity in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, 2020.

- A similar message is given by high-frequency indicators of developments in the euro area labour market, such as the Indeed job postings indicator and the LinkedIn hiring rate indicator. These high- frequency indicators reveal a large decline in labour demand and the number of job hires in the euro area since the start of the containment measures and lockdowns. For further details, refer to the box entitled “High-frequency data developments in the euro area labour market” in this issue of the Economic Bulletin. Beyond these high-frequency indicators, the survey data indicator on labour as a factor limiting production from the European Commission Business and Consumer Survey shows a sharp contraction in labour demand for all of the main sectors, with the services sector recording the steepest fall.

- The number of non-farm payroll employees in the United States stood at 152.4 million workers in February 2020 and at 132.9 million workers in May 2020. There was a slight rebound in employment between April and May, with the number of non-farm payroll employees increasing by 2.5 million workers, up from 130.4 million workers in April 2020. The unemployment rate in the United States followed a similar path to that of employment, standing at levels of 3.5% in February 2020, edging up to 14.7% in April 2020 and observing a slight rebound to 13.3% in May 2020.

- For an analysis of the US labour market, see, for example, Petrosky-Nadeau, N. and Valletta, R. G., “Unemployment Paths in a Pandemic Economy”, IZA DP, No 13294, 2020.

- The reclassification of some people from unemployment to inactivity could exert downward pressure on the unemployment rate. In this regard, monthly data on the number of inactive people could help assess how transition into activity may be affecting the observed unemployment rate. Measurement issues may also be at play in the United States, as noted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, see U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “Frequently asked questions: The impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on The Employment Situation for May 2020”, 5 June 2020.

- For further details on how short-time work schemes are affecting households’ income, see “Short-time work schemes and their effects on wages and disposable income”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, Frankfurt am Main, 2020.

- In May 2020 the Council of the European Union adopted a European instrument for temporary support to mitigate unemployment risks in an emergency (SURE).

- These figures are an upper bound to the number of workers effectively affected by short-time work schemes, as they are based on the number of initial applications by firms. These initial applications to join short-time work schemes are then subject to effective take-up rates during the time that lockdown measures were in place, which ultimately depend on the firms’ actual needs and on the acceptance of these applications by the relevant authorities. Moreover, the high number of applications was reported for the period when lockdowns were still in place and can be expected to be substantially lower over time as containment measures loosen.

- The COVID-19 pandemic is a purely exogenous shock and could lead to lower reallocation needs than an economic crisis such as the great financial crisis. For different views on the reallocation needs of the economy following the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, see Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. and Steven, J., “COVID-19 Is Also a Reallocation Shock”, NBER Working Paper, No 27137, 2020 and Kudlyak, M. and Wolcott, E., “Pandemic Layoffs”, May 2020.